Reflections: The Two & The One

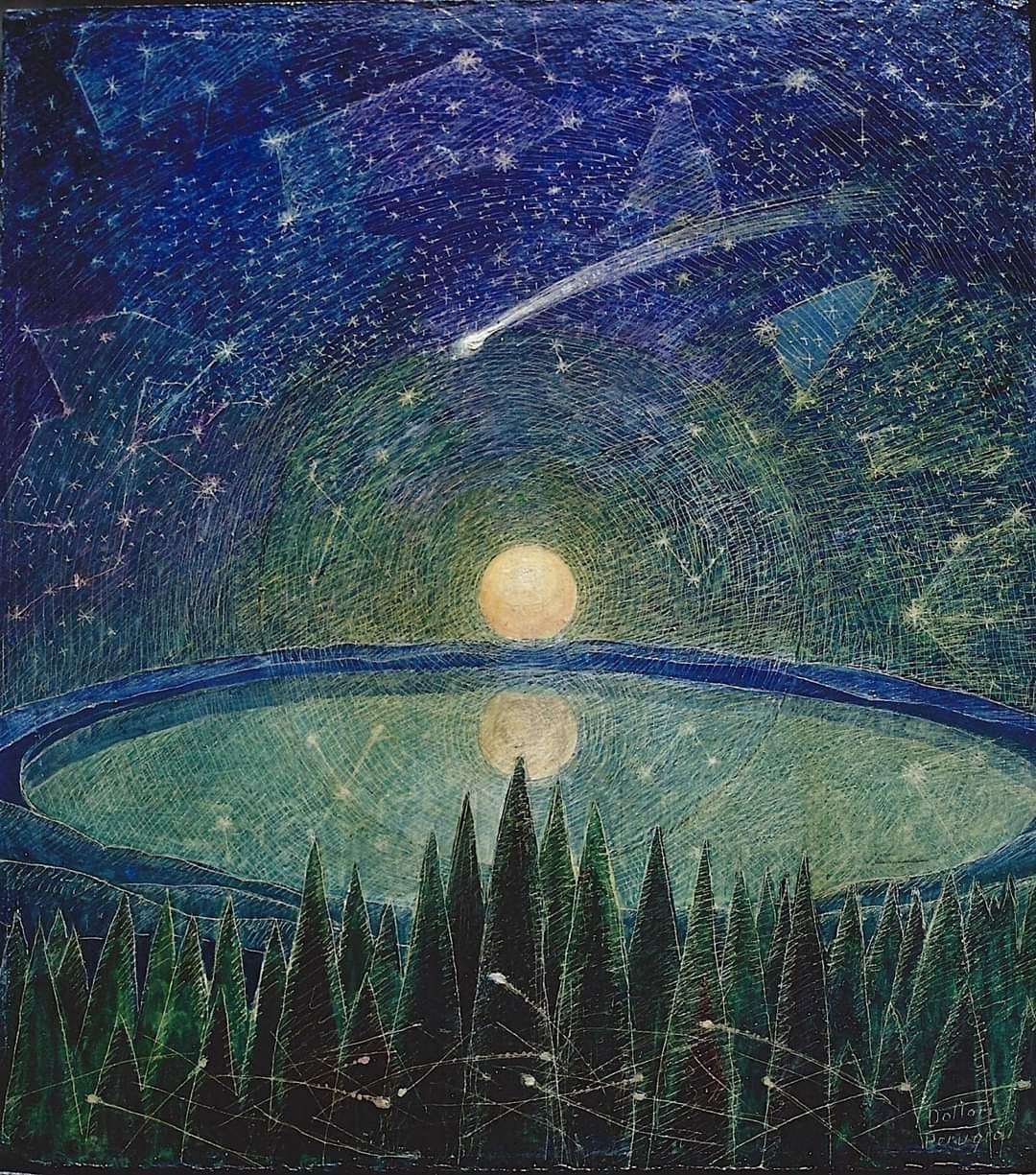

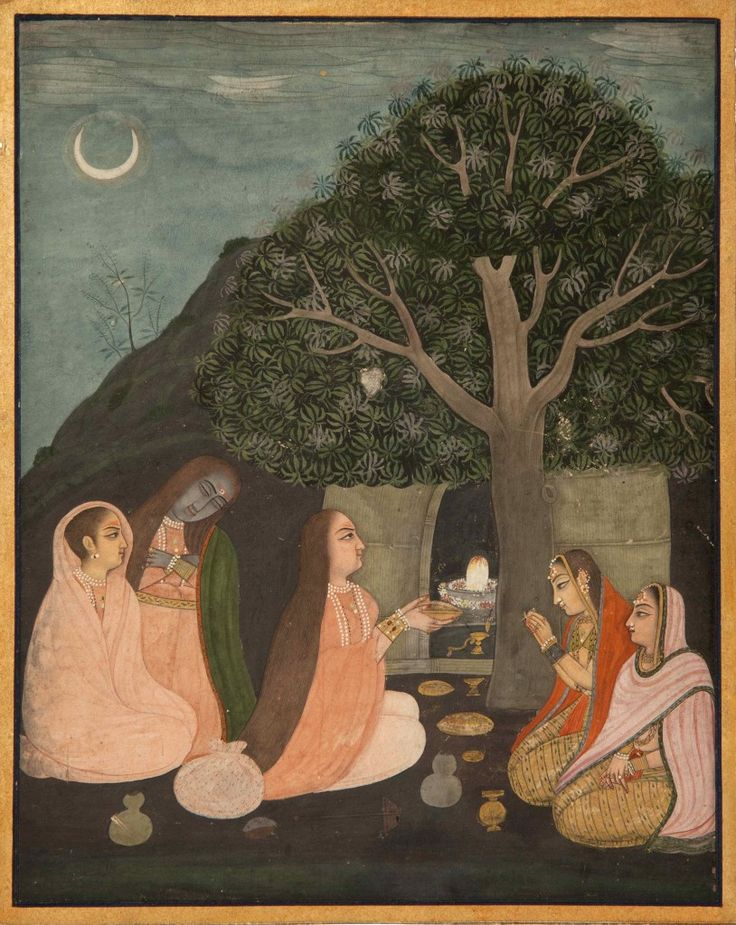

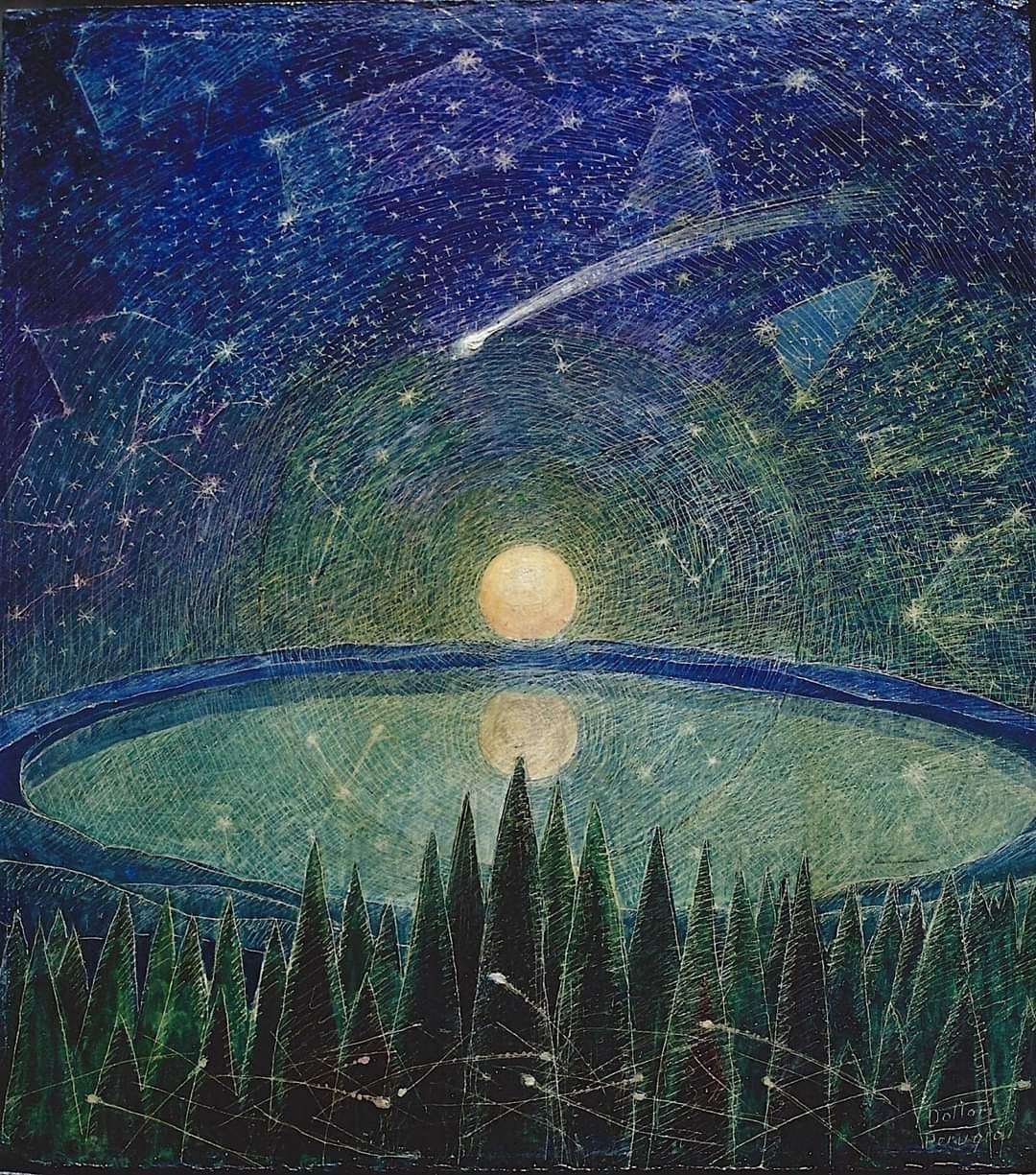

Aeons ago . . .

. . . in the mountain vale

of Kashmir . . .

two moons . . .

crowning the central tree . . .

appeared . . .

a luminous riddle:

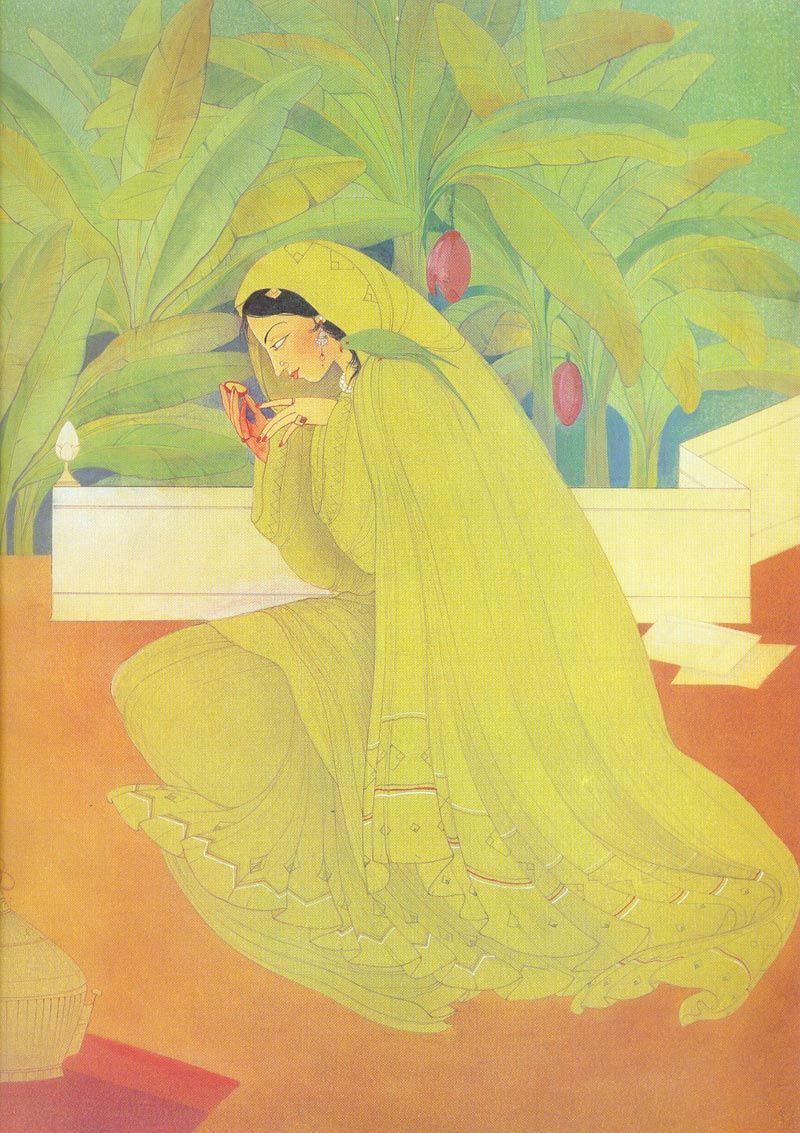

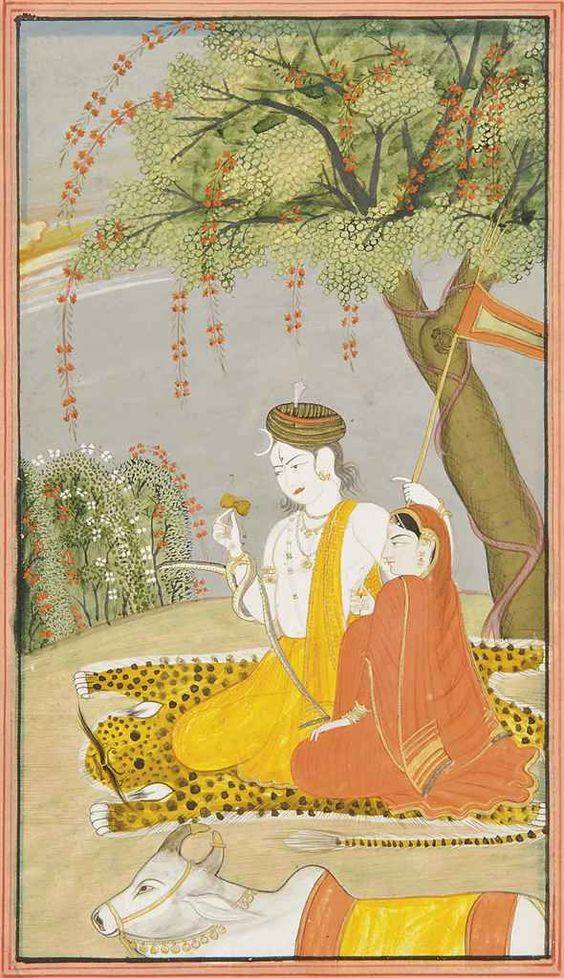

A God and a Goddess

are One . . .

Yet . . . the God knows

something Still

Unknown

to She . . . His Consort

who merely

looks on.

~

Centuries before

the God and the Goddess . . .

appeared

an earlier

riddle:

Paired companions,

occupy the same tree.

Of the two,

one eats the sweet fig,

The other,

not yet eating,

looks on.

Where birds unwinkingly celebrate

their share of life,

of the contests –

there He,

the splendid herdsman of all creation,

Wise (Soma),

entered me,

(before that) unrealizing.

Onto that tree,

honey-eating birds all alight

and mature.

Atop that tree

alone,

they say,

abides the sweet fig.

No one reaches up to it

who knows not the father.

RV 164 (20 – 22)

~

The Seers of the Rig Veda cognized riddles—enigmas. The above enigma, cognized by a blind Seer named Dirghtamas (Long Darkness), self-referentially enigmatizes the enigma-creating contests the Seers engaged in.

In that "tree" (of the contest) a master ("father") of the contest is teaching a neophyte ("son.")

Each of these two "birds" is a contestant or antagonist in the contest,

with each taking a position: either the "son's" position or the "father's" position.

Each position corresponds, respectively, either to the candidate-for-vision's position or to the gifted-with-vision (master's) position.

Two birds, paired companions

companions ........... companions or members of the contest or symposium

paired ............... of the same brotherhood of speculative symposiasts

Occupy the same tree.

occupy the same tree ..... frequent the contest ground

Of the two, one eats the sweet fig.

the sweet fig .......... the goal of the contest, speculative visionary participation in the mystery of the brahman enigma proposed by the "father"

one eats .............. participates already in inspired vision (i.e., is at the latter, "father's" position)

The other, not yet eating, looks on.

the other, not (yet) eating, looks on ......... does not participate in, has not (yet) attained speculative vision (i.e., is at the former or "son's" position, having just entered the contest ground as a candidate, as yet unrealizing and uninspired in speculative vision)

Onto that tree, the honey-eating birds all alight and mature.

Atop of that tree, alone, they say, abides the sweet fig.

No one reaches up to it who knows not the father.

Onto that tree .......... onto the contest ground

honey-eating ........... soma-drinking

birds ................ symposiasts, contestants

all alight .............. enter

and mature ........... and are transformed, achieving the inspired state

at the top of it .......... as the contest's culmination

sweet fig .............. is the goal of the contest (as above),

That [the Seer] Dirghatamas cognized the image of the tree to enigmatize this first context of Sanskritic philosophical thought was no accident, for in it he used an archetypal myth of the attainment of knowledge. The mythic complex of the cosmic or world tree, which is the tree of life or immortality, is basic to this notion of inspired, initiated knowledge. All the elements are there: the shamanic symbolisms of tree and bird, including an ecstatic journey to the top of the tree, and the initiatory symbolism of reaching the summit of the world tree to gain

the knowledge which, as the "immortal" sweetest fig, allows escape from both ignorance and death.

(Willard Johnson, On the Ṛg Vedic Riddle of the Two Birds in the Fig Tree (RV 1. 164. 20 – 22), and the Discovery of the Vedic Speculative Symposium. Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol 96, No. 2 (Apr. – Jun., 1976), pp. 248 – 258.

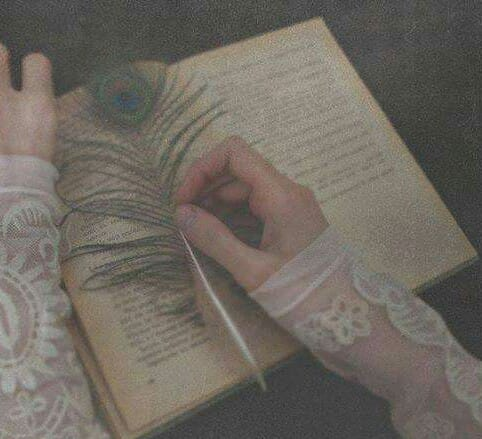

The scripture appearing on this site is the Vijñāna Bhairava. The translation (from Sanskrit into English) was a gift to me (a rather unknowing bird) from two knowing "birds," Swami Lakshmanjoo and one of his knowledgeable Kashmiri students, Pandit Dina Nath Muju.

The scripture itself is inhabited by two birds: (i) a waterfowl, the Hamsa, which resides in the tree of the Central Channel and in the subcontinent is associated with the Atman, and (like jñāna itself) with breath, and (ii) a somewhat Buddhist-leaning Peacock associated, in equal measure, with a somewhat reified concept of shunyata, Vacuity – the Void.

The mystically breathing Hamsa occupies a higher position in the tree of the scripture than does the Peacock.

To enable his commentary on this scripture to endure down through the ages, Swami Lakshmanjoo left it in two forms:

(i) a series of videos gracing each verse, which over a few years, John Hughes of the Lakshmanjoo Academy recorded, and

(ii) Swami Lakshmanjoo's textual embodiment of the tapes, The Manual for Self-Realization: 112 Meditations of the Vijñāna Bhairava Tantra (edited by John Hughes).

Both are treasures! In each, Swamiji comments on the scripture while responding to questions from his students. Swamiji emphasizes that the video version transmits his teaching with a higher level of fidelity.

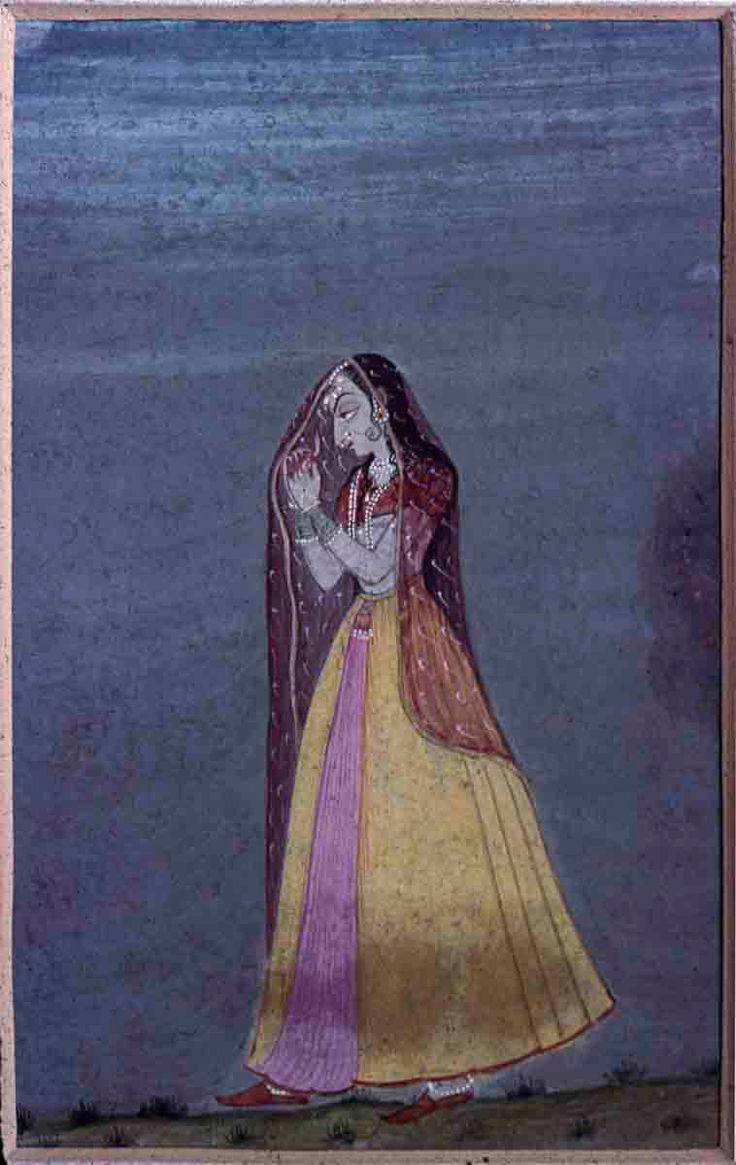

The highest position in the scripture is accorded to the scripture's first speaker, the Goddess, who speaks at length and well before even its first and fundamental (Hamsa, "Swan") mode of meditation is presented.

The Goddess recognizes that Her own ignorance is to stand at the edge of the fathomless abyss, where human certainty falters and wonder takes flight. Knowing that comprehension is but a shadow of the infinite, does She relinquish the arrogance of mere mental mastery in her surrender to the boundless expanse of the Divine?

In this surrender, rather than restlessly seeking with mind, does Her heart become a devout pilgrim of mystery rather than reason?

For to abide as Divine Consciousness, one must first embrace Unknowing—must cast off definitions and hold fast to the ineffable, as a sail grasps the wind that propels its course, without ever seeing it.

The journey of surrender itself becomes the revelation, the reaching becomes the communion, and the unknowing yields oneness with the Divine.

Unknowing gets immediately down to that Don't Talk of Love, Show Me moment. After all, acknowledging ignorance fosters surrender, which is essential for transcendence.

When we give up, we become open to new insights, interpretations, and mysteries, rather than clinging to rigid conceptual certainties.

The greatest wisdom, then, is to stand in awe, unburdened by the false comfort of certainty, and let the Infinite draw us nearer into its Full Embrace in quiet Union.

Thus, She expresses Her state of Unknowing to the God.

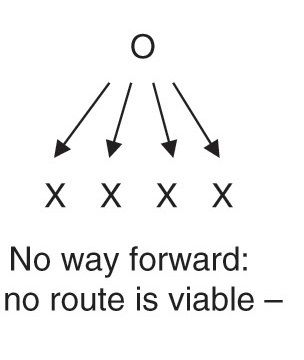

She realizes there is no way forward, that all conceptions of the way are merely mirages. They reek of mind, of mere intellect. Of givens, mere data rather than DA!

John Donne put it this way:

Negative Love

I never stoop'd so low, as they

Which on an eye, cheek, lip, can prey;

Seldom to them which soar no higher

Than virtue, or the mind to admire.

For sense and understanding may

Know what gives fuel to their fire;

My love, though silly, is more brave;

For may I miss, whene'er I crave,

If I know yet what I would have.

If that be simply perfectest,

Which can by no way be express'd

But negatives, my love is so.

To all, which all love, I say no.

If any who deciphers best,

What we know not ourselves can know,

Let him teach me that nothing. This

As yet my ease and comfort is,

Though I speed not, I cannot miss.

~

Or did the Goddess ask Herself, as did San Juan de la Cruz, this question:

How do you go on,

O life,

not living

where you truly live,

being constantly killed

by the arrows

piercing you deeply:

your mere conceptions

of the Beloved?”

Did Her mind give up, slipping away, unseen, with no other light nor guide than the fire, the fire pounding deep inside . . . Her heart an open wound of love?

Unknowing is pathless. She is not a mapped-out, eyes-clamped-shut, statuesque take on knowledge. She is not a building up, like the erection of a theological system.

She is a licking away, a lingo of erosion, a melting away, a scoop of mango ice cream dissolving on the tongue. She dances into each living moment: a djinn or genie flailing rhapsodically her thousand-thousand arms, pounding out silent heartbeats at full-universe scale.

She weaves, moment to moment, surrenderings woven of wonderment, of breathtaking awe, evanescing and swooning into awakening.

She teases forth our sensitivities to the impalpable, the ungraspable, as when trying to crunch an impossible math problem, the mind draws a blank.

Or when we have two dashing suitors but cannot decide betwixt and between the two.

Or when the Mandukya Upanishad insists that Truth cannot be grasped by mind.

In that moment of intellectual impasse—we surrender to unknowing, transcending all thought.

The Vijñāna Bhairava begins with the Goddess’ frustration at not being able to grasp the essence of the scriptures.

Usually the active, dancing, dynamic half of the Divine Duo, She gives up, leaving the God, Her "better half," to annunciate all 112 ways of meditation.

Yet, she has already embodied the essence of all means of transcendence that the God will soon announce in Verse 112:

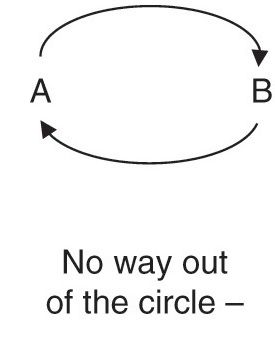

When the mind feels frustrated

because it cannot grasp the meaning

of some book, or problem,

when it becomes a darned-if-you-do,

darned-if-you-don’t frustration,

with no way out,

mind gives up

relaxing

into

mental impasse,

aporia,

a state of blissful

unknowing.

Emily Dickinson put it this way:

This World is not Conclusion.

A Species stands beyond —

Invisible, as Music —

But positive, as Sound —

It beckons, and it baffles —

Philosophy, dont know -—

And through a Riddle, at the last —

Sagacity, must go —

To guess it, puzzles scholars —

To gain it, Men have borne

Contempt of Generations

And Crucifixion, shown —

Faith slips — and laughs, and rallies —

Blushes, if any see —

Plucks at a twig of Evidence —

And asks a Vane, the way —

Much Gesture, from the Pulpit —

Strong Hallelujahs roll —

Narcotics cannot still the Tooth

That nibbles at the soul —

When we recognize ourselves as Shoreless Awareness abiding beyond mind — then!

By giving up before the God even begins enumerating all the methods, the Goddess recognizes that by simply abandoning mind, She is the source, course, and goal of all the 112 meditations the God is about to impart to her.

Shhhhhh! Don’t tell the God!

Don't mention that some scholars opine the scripture was penned by a woman.

After all, many of its ways of meditation, its means, are based on perceptions Kashmiri women enjoyed during their daily chores: bathing, for instance, within the shoreless ripplings of their awareness when it becomes absorbed within the dark hollow of a water pot or a village well, or the luminosities within silence-haunted mantras.

Swamiji was aware that the fruits of the methods described in these verses are beyond mind. He likened the methods themselves to the sweets a loving mother spoons onto her child's tongue to help the medicine go down.

Knowing of the "terrible medicine," of "doing nothing," as Swamiji characterizes it, is fundamental but hard to digest. The means help one digest it.

This so-called medicine is simply the difficulty of realizing that the meaning of the scripture, Divine Awareness, is not an object to be known and that any mind attempting to know Divine Awareness mentally will—like a blind person seeking to know what one is touching—merely, by doing, continue circling the elephant.

If Divine Awareness is not a knowable object of knowing . . . what is it?

Divine Awareness is simply one's own shoreless ocean of consciousness, not as Knowing, not as the Known, but as the Knower (Consciousness knowing Consciousness by means of Consciousness).

After all, if we are seeking to Know anything, we must first realize the Knower.

The "terrible medicine" is the realization that there is no thing one can do to know what one already is.

One's Divine Awareness abides beyond one's thinkings and doings.

The cure: thinking and doing less and less and less and less . . .

And, for the duration of many dozens of verses . . . the mind of the Goddess . . . showing no evidence of activity . . . remains silent . . . does nothing.

When the mind remains completely still, its thought structures have evaporated.

It is as though the usually dynamic Goddess and the usually quiescent God imparting knowledge to Her have reversed roles.

But for the Goddess, there is nothing circling the elephant of her own Shoreless Awareness, Knower-Knowing-Known as One!

According to Verse 112 of the scripture, it is precisely within such moments of mental impasse, of Unknowing, that one recognizes one's own awareness as Divine . . . beyond thought constructs, fully enjoying the sweet fruit of all the 112 methods.

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

Religious Studies is an academic discipline. It is of the intellect, which cannot fathom the Divine. The study of religions is not an autonomous academic discipline but draws upon other fields: anthropology, philology, linguistics, history, sociology, psychology, art, theology, semiotics, literary theory, music . . . and their deconstructions . . .

Sociologists, anthropologists, and psychologists of religions may engage in research on the social structures underlying a scripture's mythological structures, including their theologically implied portrayals of gender relations.

Thus, if a scripture has one axis connecting itself with the reader, it has another connecting itself with a field of other texts.

These might include texts within the scripture's own genre as well as texts within the scripture's general cultural milieu—and well beyond.

For instance, some Kashmiri texts of the era (such as those of Kshemendra, who was a talented student of Abhinavagupta) emphasize the limited freedoms and opportunities Kashmiri women of that era enjoyed. They are well worth reading.

They are especially worth reading because some scholars surmise, as already mentioned, that the scripture itself may have likely been written by a woman.

If so, did the scripture's author countenance the similar types of gender-related challenges the famous Kashmiri poet and mystic Lalleshwari confronted a few centuries later?

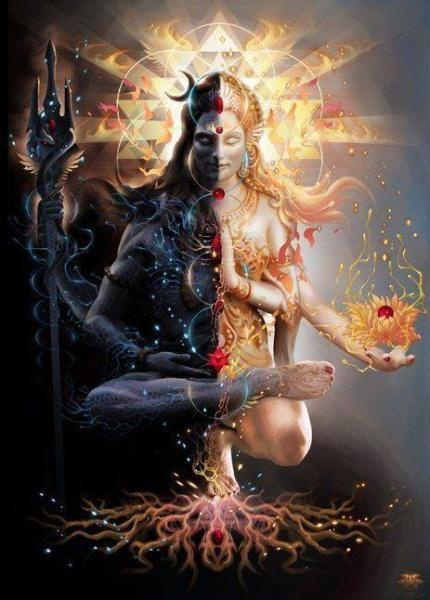

Viewed dualistically, on the surface, narrative level of the text, we have a God, Bhairava (a then-popular form of Shiva), displaying His understanding of a tradition He embodies.

In fact, as Shoreless Awareness, He is thought of as abiding as the very essence of the tradition, with His discourse occupying most of the scripture.

As mentioned, we also have a Goddess, Bhairavi, His consort, who claims not to grasp the essence of the tradition's writings.

Viewed in a non-dual mode, however, these two mythic figures of that era represent two aspects of One Divine Reality: the God being the Quiescent Ocean of Shoreless Awareness and the Goddess the Creative Waves embodying that pure Mass of Consciousness.

When, at the beginning of the scripture, the Goddess becomes fruitlessly exhausted in her attempts to think Her way into the essence of what She sees as Her objects of study—She simply throws in the towel. Or feigns doing so.

It is only after having given up, though, that She announces Her state of Unknowing, of having exhausted what She had considered to be Her only viable route to knowledge: the mind.

Had She, however, in the process, already relaxed into a state of mental impasse, of seeing no forward path: of aporia? A pathless path?

Astute readers may notice that the numeration of Verse 112 is identical to the number of the scripture's many ways (112), most of which Lakshmanjoo illuminates in his commentary.

We now know that Verse 112 informs us that a mental impasse can act as a path leading to the realization of Divine Awareness.

Verse 112 teaches that when the mind lacks the ability to mentally grasp an object of knowledge, the mind, in giving up, may dissolve into Divine Awareness.

Some readers may have concluded that having found Herself out of Her own depth, and having given up mentally, the Goddess's awareness must have, as the scripture itself describes, silently, subtly unveiled its own boundless state.

As Lakshmanjoo has pointed out in his commentary, this can happen when the mind gives up trying to comprehend an Object of Knowledge and dissolves into the Shoreless Awareness of the Knower.

Aporiae (the plural of aporia) are, after all, often followed by illumination.

Has the God even noticed that the Goddess—in giving up—has already, as per Verses 112 & 127, gone beyond thought and thus fulfilled the aim of each of the 112 methods He is about to describe to Her?

Is the female half of the Divine Dyad only feigning ignorance? After all, the God, Her other half, is eternally one with Her, so "His" presentation of the means of abiding as Divine Awareness, is also "Hers."

Switching back to a dualistic perspective, if He did not notice Her state, it may be because the Divinity of Her unknowing state is merely implied. Though She admits She cannot get to the essence of the tradition, the Scripture merely implies that She has in fact gotten to the essence as a result of Her mental impasse, by going beyond mind.

Thus, the scripture "tells" it "slant," to place it within Emily Dickinson's parlance.

Though the scripture may have been written in the 7th or the 8th century, it was not until the 9th century that Ānandavardhana, in his Light on Suggestion (or Implication), revolutionized Indian poetics with his insights into innuendo, dhavani, which is a popular name for Indian women.

[A pertinent lesson on implication: When a woman asks her husband if he feels a draft in the room, the meaning of the question often may not be what the words actually denote on a word-by-word basis. It may not even be a question. It may be an imperative sentence. The real meaning of her sentence may really be something like the following: "Honey, please get up and shut the window."]

Even before implication and suggestion had become officially and theoretically elaborated in India, scriptures and other genres of Sanskrit were not-so-quietly overflowing with gender-related innuendo and implication.

In classical Sanskrit dramaturgy, women are often portrayed with rich emotional complexity and spiritual depth. Their actions, expressions, and especially silences are rich with implied meanings.

Within relationships, implications center on female characters because they were often the ones bearing the emotional burden of a relationship. Because Indian women lived in a patriarchal society, their longing, restraint, and internal conflicts were often expressed more through suggestion than through direct speech. They were also bound by societal norms, forcing them to express their desires obliquely as the only option, often resorting to gesture, metaphor, or silence. A single glance, a pause, or a poetic metaphor can evoke śṛṅgāra (romance) or karuṇa (pathos) with great subtlety.

For example, in Bhavabhūti’s Uttararamacarita, Sītā’s silence and restraint speak volumes about her dignity and suffering, conveying more feeling more poignantly than can spoken dialogue.

Similarly, in Diṅnāga’s Kundamālā, the character of Sītā is surrounded by scenes of quiet implication: her exile, her pregnancy, her reunion with Rāma, all dramatized with emotional nuance and indirect expression.

Implication thus becomes a form of female power. These women act through silence, leading the narrative through suggestion, restraint, and emotional intelligence. For this reason, feigned ignorance (mugdhatā or mānavinaya) appears as a subtle and recurring motif in Sanskrit poetics, especially in the portrayal of women.

In classical Sanskrit drama and poetry, particularly in romantic contexts, women characters sometimes pretend not to understand something: usually love, desire, or social cues. This is a facet of śṛṅgāra rasa (the aesthetic of love), where emotional nuance is everything. A heroine might feign ignorance of a lover’s intentions, creating playful tension. To maintain decorum or avoid embarrassment in conservative settings, she might pretend not to grasp a topic. Feigned ignorance can mask deeper feelings, such as longing, jealousy, or vulnerability, while preserving dignity.

In Kālidāsa’s Abhijñānaśākuntalam, Shakuntalā often embodies this trait. Her hesitation and indirect speech suggest deeper emotions she’s not ready to express openly. In Bhavabhūti’s Mālavikāgnimitram, Mālavikā, the heroine, uses feigned ignorance to navigate courtly love and maintain her mystique. Also, many short poetic aphorisms (subhāṣita verses) celebrate the charm of a woman who “does not know” she is beautiful or loved (though the reader knows she knows).

In addition to flirtation, feigned ignorance provided Indian women with a way of expressing power. It allowed women to control the pace of emotional revelation, to protect themselves, or to test the sincerity of others. In a culture that always prized indirectness and suggestion (dhvani), this kind of subtle play was deeply admired.

There are also many compelling examples of women using implication (dhvani-like suggestion) in Sanskrit literature long before the formal theory of dhvani was instituted by Ānandavardhana in the 9th century.

The tradition of subtle, indirect expression, especially through female voices, runs deep in Vedic, epic, and early poetic texts.

Vedic poetesses such as Lopāmudrā and Apālā composed hymns in the Ṛgveda that are rich in emotional and symbolic suggestion. Lopāmudrā’s hymn to Agastya (Ṛgveda I.179) subtly implies her desire for conjugal union, cloaked in metaphysical language. She evokes love through suggestive metaphor.

Apālā, rejected by her husband due to a skin disease, prays to Indra for healing (Ṛgveda VIII.80). Her verses imply both suffering and resilience, without overt complaint.

These hymns are emotionally charged and indirect, invoking dhvani in spirit, if not in name.

In the Mahābhārata, Draupadī often speaks in silences. Her silence during her disrobing, followed by her cryptic invocation of Kṛṣṇa, displays a moment of implied divine protest and moral indictment.

Sītā, in Vālmīki’s Rāmāyaṇa, uses implication masterfully. Her words to Rāma before her exile are restrained but loaded with emotional and ethical undertones.

In the Vijñāna Bhairava Tantra, Bhairavī feigns ignorance not because she actually lacks knowledge but to elicit deeper teaching. This is a classic tantric motif: the feminine as the initiator through her apparent passivity.

Thus, implication, "telling it slant," as Emily Dickinson would put it, often serves as a necessary mode of expression for women in patriarchal contexts. It allows them to masterfully navigate social constraints, express agency without confrontation, and evoke deeper emotional and philosophical truths. So, know that long before dhvani was theorized, women in Sanskrit literature were already its most eloquent practitioners.

In this regard, verse 112 of the Vijñāna Bhairava Tantra stands as one of the most radical, subtle, and fundamental insights in the entire text. The verse proposes "unknowing" (ajñāna, or more precisely, the dissolution of conditioned knowing) as a direct path to the realization of Bhairava, Divine Awareness. It serves a meditative technique (yukti) wherein the practitioner floats in the ether of broken-down perception, confusion, disorientation, or illusion, as a gateway to Formless Divinity. This formative yukti forms the ground state of the tantric view that every experience, including unknowing or absence, can function as a portal to the Absolute. It’s a radical truth of the non-dual in which even the failure of cognition opens to the Sacred.

After all, often unnoticed, women everywhere, moonily amusing themselves within the relative obscurity of their own creative grottos, have often secretly revolutionized their fields of endeavor.

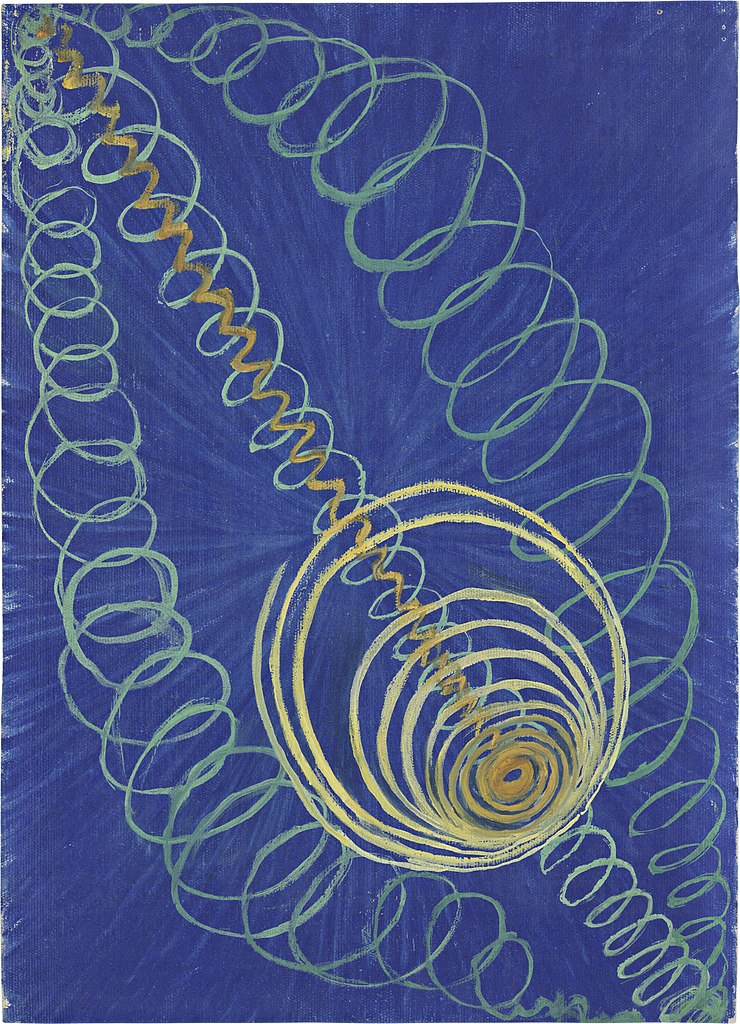

One example is the Swedish artist and mystic Hilma af Klint (1862 – 1944), a revolutionary whose phosphene-like paintings have only recently been recognized as among the first abstract works in the history of Western art.

Much of her collection predates the paintings of the male artists credited as the originators of the movement—Kandinsky, Malevich, and Mondrian.

Similarly, although men got the credit for first walking on the moon, it was an unsung, unassuming female computer programmer, Margaret Hamilton, who actually had the "right stuff" to recognize the need for computer code that actually got those men to the moon and back—with nary a software glitch on any of the Apollo missions!

In short, with the help of her baby, she proactively goof-proofed their software.

If the Vijñāna Bhairava was written by a woman, it should not surprise us if its quiet and gentle gender innuendos venture beyond mere metaphor to pioneer powers of the written word that did not begin to frequent male-dominated Sanskrits until centuries later, when innuendo and implication began to actively form a new dimension in Sanskrit verse.

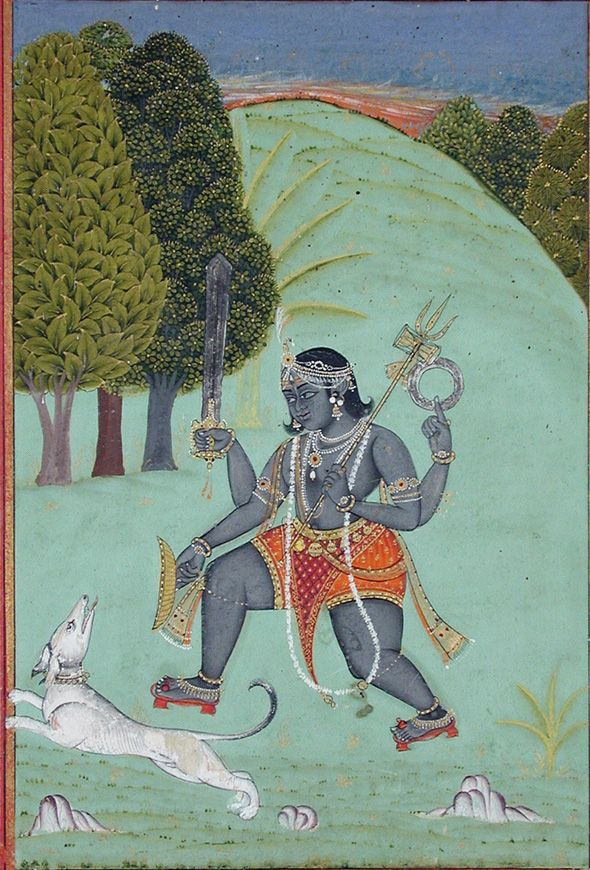

The God, while His consort remains silent, begins spreading out His array of meditation techniques like a courting peacock unfolding his tail feathers.

In fact, the image of the peacock is one of the most enduring in the Indian subcontinent, and beyond.

In Biblical times, King Solomon imported a peacock from India all the way to Egypt. And when the Queen of Sheba visited him, she brought along her own retinue of peafowl.

Peacock courtship eventually developed into one of the most common tropes of romantic Indian monsoon verse.

From the sastras, we learn that the Divine form presiding over grammar is seated on a peacock and that the thirty-two forms of Sakti corresponding with the thirty-two forms of Aghora Murti (a form of Siva) have as their vehicle the peacock.

The Siddhasabara Tantra describes the beings presiding over the letters ai, o, na, and dita as being seated on a peacock.

And so, take note of how, when the Goddess of the scripture confesses Her inability to grasp the essence of the philosophies of the tradition intellectually, the God of the scripture aces the moment. As in the mating dance of a strutting peacock, He begins spreading out His array of "feathers": their scintillating rainbow of mystic "eyes" reaching into infinity.

Seen in this light, Verse 112 of the scripture is a "feather" focusing on mental impasse.

Another verse, another one of the "feathers," Verse 36, actually focuses on a peacock feather.

Is the creator of the scripture here gliding from mere implication into a brazen hint?

After all, consider the following: in objective reality, peacocks dance before peahens by splaying out their tailfeathers, about 150 of them (just a bit more than the actionable verses in the scripture, though the total of method-related verses is more).

Among peacocks, this dance is vibratory.

As the male dances, his tail feathers hum along at twenty-five cycles per second, causing the "eyes" of the feathers to appear as if hovering in space—vibrationally.

Scientists have recently discovered that, according to the laws of physics, the finer and more feminine feathers adorning the crowns of peahens' heads then begin to entrain vibrationally: in unison with the frequency of the male's tail feathers!

These good vibrations often result in the creation of baby peafowl.

And, as the tradition suggests in explaining the relationship between consciousness and its infinitely diverse expressions: all the resplendent iridescence of the peacock's tail feathers is present in nascent form within the yellow yolk of the peahen's egg.

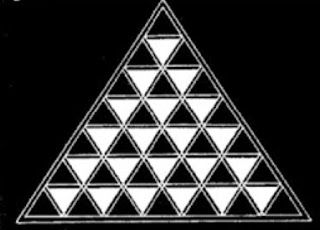

Another kind of aporia that can lead to a mental impasse and then illumination is circular.

For instance: the relationship between consciousness and its expressions, unity and diversity, as well as the two-in-one relationship between Bhairava-Bhairavi are mirrored in the logic of a paradox formulated by the Indian grammarian Bhartṛhari.

Though the paradox is only one statement, it eternally vibrates back and forth between two semantic poles, giving rise to an endless interplay between two meanings.

The paradox reads as follows: Everything I say is a lie.

(Hint: If it's true it's false; if it's false it's true.)

It appears we cannot stop the meaning of paradox from oscillating, throbbing, pulsing from one pole of one meaning to the other, and then back again . . . endlessly . . .

Further, Bhartṛhari's liar's paradox brings to mind the aporia inherent in Verse 133 of the scripture: the teaching that the whole universe (including, by definition, Verse 133 and the entirety of the scripture's other verses) is a magic trick.

When flabbergasted by a magic trick, only after the astonishment fades away does one realize it had been "only" a trick, an illusion: not at all "real."

Thus, if the words of the verse are truly a trick (untrue), it is true. If the words of the verse are truly true, the verse is untrue.

In other words: If this verse on magic applies to itself, then its statement that everything is only a trick is also only a trick.

If the statement is real, it's not real. If the statement is unreal, it's real.

And if the statement applies to all the other methods in the scripture, they are all birds of the same feather, vibrating back and forth between true and false, fullness and emptiness, just like Shiva and Shakti.

Neti Neti Nabobs Take Note:

Not only do two pairs of birds (the Goddess and the God, the Hamsa and the Peacock) nest in the same scripture, two "birds" also indwell each of the scripture's 112 verses pertaining to means.

Most of these verses are inhabited by two stanzas: first, an unknowing, merely- looking-on stanza and a second, an eating-the-sweet-fruit-of-the-tree stanza.

Most of the 112 unknowing stanzas pertain to a method and usually begin by describing subtle experiential ephemerealms within Medieval Kashmir's day-to-day realities (breaths, peacock feathers, monsoon nights, vast and featureless landscapes, deep sighs, caverns, and so on).

Then, in the second stanza, the verse will leap semantically to a mysterious referent—Divine Awareness: which is for the unknowing reader, an Ungraspable fruit. An Unsignifiable referent.

At times, for instance, the sweet, Unsignifiable fruit is signified by the word Void, a Void pointing to the very purpose and meaning of each verse.

With each word we read in each verse, we are lowering ourselves, word by word into a deep cavern—and we realize, in a flash, we are stuck. We are stuck because neither the first stanza nor the second is going to deliver the sweet fruit of Divine Awareness to us.

When we realize this, we realize we can proceed neither up nor down. With respect to our goal of Absolute Truth, we have reached an impasse. Of course, we are free to nibble away on the sweet "candy," on one of these means, as Lakshmanjoo points out.

The first Stanza of each Verse is like the Unknowing Bird, the second is like the Knowing Bird, while the foundation of Knowing, the Knower, abides eternally in the gap beyond the two.

Breathing, imagining, sneezing, contemplating, walking about: all are words that have referents in the world as we know it.

Where, however, for seekers, resides, the referent to the expression Divine Awareness?

Seekers must surmise that, somehow, this elusive Divine Awareness, whatever it is, seems to abide some"where" as the very Meaning of every verse: indeed the Meaning of the entire scripture, and the Meaning of life.

Thus, if we truly knew ourselves as Divine Awareness, we would feel no need to consult the scripture or practice its methods.

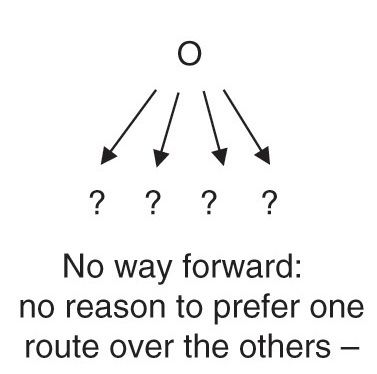

This brings up the question of which of the 112 methods to practice. Which piece of candy to select?

This question itself, however, according to verse 132, makes up another practice: of Ungraspability.

Luckily, another type of aporia arises when trapped in a paradox of choice, for instance: Which fellow shall I marry?

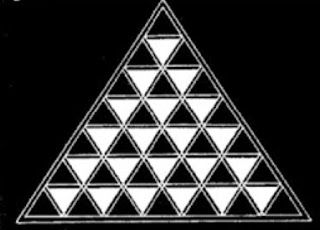

(In the above schematic representation, this type of aporia resembles an array of peacock feathers radiating from a single eye.)

And perhaps one of the most efficient and mathematically elegant ways of leaving all thought aside and residing as Shoreless Awareness would be to become so mired in undecidability when contemplating which of the scripture's methods to adopt, that the seeker settles on none: none-hood . . .

Although paradox often leads the mind to a state of suspension—a felt sense that the mind realizes it has no path forward—that is a good thing.

After all, the Goddess posing as one who confesses She is not able to understand the teachings of the tradition leads to Her better half describing the 112 ways for all of us non-Goddesses.

An aporia often precedes a sudden epistemic shift beyond mind—into spiritual illumination.

For instance, Arjuna, in the Bhagavad Gita, was considered to be India's greatest archer. Yet, all of Arjuna's knowledge of the scriptures and of dharma did not prevent his mind from falling into a state of aporia, which immediately preceded his spiritual illumination.

Arjuna was the unknowing bird sitting above the axle-tree of his chariot with his "knowing bird" and cosmic charioteer, Krishna.

His illumination unfolded on the battlefield only when he laid down his bow in the battle between mind and heart, thus entering a state of pathless inaction.

Aporiae are universal. They indwell, for instance, the Socratic method, especially in Plato's early dialogs.

MENO: Socrates, I certainly used to hear, even before meeting you, that you never did anything else than exist in a state of perplexity (aporia) yourself and put others in a state of perplexity. And now you seem to be bewitching me and drugging me and simply subduing me with incantations, so that I come to be full of perplexity. And you seem to me, if it is appropriate to make something of a joke, to be altogether, both in looks and other respects, like the flat torpedo-fish (narkē, stingray) of the sea. For, indeed, it always makes anyone who approaches it grow numb, and you seem to me now to have done that very sort of thing to me, making me numb (narkan). For truly, both in soul and in mouth, I am numb and have nothing with which I can answer you. And yet thousands of times I have made a great many speeches about virtue, and before many people, and done very well, in my own opinion anyway; yet now I’m altogether unable to say what it is. And it seems to me that you are well-advised not to sail away or emigrate from here: for, if you, a foreigner in a different city, were to do this sort of thing, you would probably be arrested as a sorcerer. [Plato’s Meno 79e-80b. From the translation of Berns and Anastaplo, Focus Philosophical Library, 2004, as quoted in Woody Belangia, "The Uses of Aporia, The Torpedo Fish Analogy in Plato's Meno," on the website Shared Ignorance: Towards a Defective Reading of Plato. The uses of aporia: the torpedo-fish analogy in Plato’s Meno | shared ignorance (woodybelangia.com) ]

Aporiae also indwell the philosophical methods of thinkers such as Pyrrho, Timon, Arcesilaus, Diogenes, and Sextus Empiricus. Sextus was quite explicit about the connection between skepticism and the aporetic method, arguing that the skeptic way be embraced as a way of life (agoge) or disposition (dunamis), and that the suspension of judgment (epoché) helps us achieve inner tranquility or peace of mind (ataraxia).

See also On What Cannot Be Said: Apophatic Discourses in Philosophy, Religion, Literature, and the Arts.

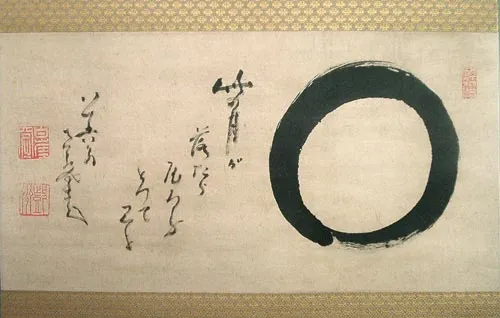

Anthropologist Michael Jackson explains how, in another realm, during the beginning of China's Sung dynasty, aporiae in the form of paradoxical words arose among Chan (the precursor of Zen) masters.

The T'ang period developed these into the koan: a mystifying puzzle forcing one to abandon mentation and open to new ways of (un)knowing—such as immediate experience.

Thus, the Goddess Bhairavi was not the only mythic female character to have immediately experienced an aporia leading to illumination.

Another unknowing bird, among many such figures, was the legendary nun Chiyono: famous for having written the following no-nonsense poem, here pared down to its minimal core:

No water –

No moon.

The longer version involves a story:

CHIYONO [MUGAI NYODAI]

from Richard Bryan McDaniel: Zen Masters of Japan. The Second Step East. Rutland, Vermont: Tuttle Publishing, 2013.

One of Bukko’s students was the first Japanese woman to receive a certificate of inka. Her Buddhist name was Mugai Nyodai, but she is remembered by her personal name, Chiyono. She was a member of the Hojo family by marriage and a well-educated woman who long had an interest in the Dharma. After her husband died and her family responsibilities had been fulfilled, she went to study with the Chinese master. After completing her studies with Bukko, she became the founding abbess of the most important Zen temple for women in Kyoto, Keiaiji.A teaching story with no apparent basis in fact suggests that before coming to study with Bukko, Chiyono had been a servant at a small temple where three nuns practiced Buddhism and hosted evening meditation sessions for the laity. According to this story, Chiyono observed the people practicing zazen and tried to imitate their sitting in her quarters, but without any formal instruction, all she acquired for her efforts were sore knees. Finally she approached the youngest of the nuns and asked how to do zazen. The nun replied that her duty was to carry out her responsibilities to the best of her abilities. “That,” she said, “is your zazen.”Chiyono felt she was being told not to concern herself with things that were beyond her station. She continued to fulfill her daily tasks, which largely consisted of fetching firewood and hauling buckets of water. She noticed, however, that people of all classes joined the nuns during the meditation sessions; therefore, there was no reason why she, too, could not practice. This time she questioned the oldest of the nuns. This woman provided Chiyono with basic instruction, explained how to sit, place her hands, fix her eyes, and regulate her breathing.“Then, drop body and mind,” she told Chiyono. “Looking from within, inquire ‘Where is mind?’ Observing from without, ask ‘Where is mind to be found?’ Only this. As other thoughts arise, let them pass without following them and return to searching for mind.”Chiyono thanked the nun for her assistance, then lamented that her responsibilities were such that she had little time for formal meditation.“All you do can be your zazen,” the nun said, echoing what the younger nun had said earlier. “In whatever activity you find yourself, continue to inquire, ‘What is mind? Where do thoughts come from?’ When you hear someone speak, don’t focus on the words but ask, instead, ‘Who is hearing?’ When you see something, don’t focus on it, but ask yourself, ‘What is that sees?’” Chiyono committed herself to this practice day after day. Then, one evening, she was fetching water in an old pail. The bucket, held together with bamboo which had weakened over time, split as she was carrying it and the water spilled out. At that moment, Chiyono became aware. Although the story about her time as a servant is certainly apocryphal, the part about the broken pail precipitating her enlightenment seems to be based on her actual experience. She commemorated the event with these lines:

In this way and that, I tried to save the old pail since the bamboo strip was weakening and about to break until at last the bottom fell out. No more water in the pail! No more moon in the water!*

*Paul Reps, Zen Flesh, Zen Bones (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, no date), p. 31.

Not having been born into Sanskrit, Paul Reps may never have been able to bask in the full sunlight of the Vijñāna Bhairava's Sanskrit.

Rather, his renderings shine like photographic film exposed to moonlight: fugitive traces of lunar atmospherics brushing up against a bare, zen-sensitized membrane.

Reps' aesthetic sensibilities, even though mired within his Indic linguistic limitations, have much of value to offer.

Sitting in Kashmir with Swami Lakshmanjoo as he penned his renditions of the scripture, it would have been impossible for the poet not to have immediately recognized a structural affinity between the forms of much haiku and waka and the verses of the VBT.

I say this because almost every haiku juxtaposes—at first glance inaptly and ineptly —two contrasting images.

Often, the two images seem not to compute . . .

my head

in the clouds

in the lake

. . . until they do.

The poem’s electricity happens when the lightning of awareness suddenly leaps into the Void between these two esoterically apt—but at first seemingly ill-paired —poles: like two bodies of two star-fated lovers bumping up against one another in a slightly dangerous nightclub.

The flash is like the moment we laugh at a pun. To wit:

A Quantum Structure Description of the Liar

Paradox

*

Diederik Aerts, Jan Broekaert and Sonja Smets

Center Leo Apostel (CLEA),

Brussels Free University,

Krijgskundestraat 33, 1160 Brussels

diraerts@vub.ac.be, jbroekae@vub.ac.be

sonsmets@vub.ac.be

Abstract

In this article we propose an approach that models the truth behavior

of cognitive entities (i.e., sets of connected propositions) by taking into

account in a very explicit way the possible influence of the cognitive

person (the one that interacts with the considered cognitive entity).

Hereby we specifically apply the mathematical formalism of quantum

mechanics because of the fact that this formalism allows the descrip-

tion of real contextual influences, i.e. the influence of the measuring

apparatus on the physical entity. We concentrated on the typical situ-

ation of the liar paradox and have shown that (1) the truth-false state

of this liar paradox can be represented by a quantum vector of the non-

product type in a finite dimensional complex Hilbert space and the dif-

ferent cognitive interactions by the actions of the corresponding quan-

tum projections, (2) the typical oscillations between false and truth -

the paradox -is now quantum dynamically described by a Schrodinger

equation. We analyze possible philosophical implications of this result.

When we laugh at a joke based on a pun, we forget about everything, roll on the floor, and time and space collapse into laughter.

In fact, zen poets, quantum physicists, and psychologists study puns (kake kotoba 'hinge words') as Classical World (Samsara) analogs of quantum world (Nirvana) phenomena.

In this way, similarly to how the great Kashmiri thinker Abhinavagupta paired rasa aesthetics with ontology and soteriology, haiku and waka verse commonly arrive at a haiku moment: an ah moment when the difference between Samsara and Nirvana collapses—laughed out of existence.

Each way presented in the VBT is similarly structured, similarly endowed with two disparate images: each dawning in the sky of its own stanza, illumining its own unique semantic horizon.

Again, each of the practicum verses of the scripture presents a certain means.

Second, between the two stanzas, a gap.

And only third, usually in the second stanza, a leap pointing to the projected result of that means.

The nouns and verbs in the first stanzas are empirically familiar: pots to be gazed into, inhalation, exhalation, dark nights.

The referent of the second stanza, announcing the projected result, however, usually remains unknown to most readers, or they would not be reading the scripture.

Second-stanza signifiers do not, at first, resonate with their transcendental signified.

It is because of this, that Bhartṛhari's issue of nameability, of signifiability, arises.

The words Divine Awareness do not deliver Divine Awareness.

Until they do.

In this way, the semantic how-to language game of the first stanza collapses in that of the second: where the referent is the Knower, consciousness endlessly playing hide and seek within Itself.

Thus, the aporia. The mental impasse. Is the path of this magic.

Reps realizes—like Patanjali and the Sanskrit grammarian Bhartṛhari—that minimalism rests lightly on the mind, more effortlessly conveying the meaning-whole of a verse.

Many readers realize that neither haiku nor the verses of the VBT are really about the words on the page. They are about the meaning of Meaning.

Those black marks on the page are but scars of spiritual-aesthetic lightning.

Both in Abhinavagupta’s poetics and in the zen-inspired haiku poetics informing Reps' renderings, aesthetic experience can act analogously to unitive spiritual realization.

The flash of a haiku’s aha moment can be so vertiginously alluring, so suddenly illuminative and unitive that it flashes forth in the formless form of a mini-realization: a little piece of Samsara suddenly recognized as Nirvana, the realms of Classical Physics and Quantum Physics, as one.

This is why some types of haiku and waka use kake kotoba, hinge words (puns).

Structurally considered, then, much haiku and many of the VBT verses are founded on a somewhat similar aporetic compositional logic.

This aporetic structure primes the reader's mind to receive, recognize, and be these sudden, unexpected, illuminative flashes of awareness.

Consciousness, being both quiescent and dynamic, purely intelligent and dynamically creative, operates as something of a self-referential ruse—just like waves, which never cease being Ocean.

Because Bhairava and Bhairavi are actually One, the Goddess's feigned ignorance and their ensuing dialog are (Rudric) ruses as well. Bhairavi moves the aporia from the realm of the verses to the realm of the scripture as a whole.

That mystery between unity and diversity is where the magic resides. Om is where the art is.

It is likely that Reps, with his background in zen, at times attempted to skew his VBT versions in the direction of the Buddhist school of sudden enlightenment.

In Shiva’s capacious triadic heart, enthusiasts such as Reps (and others) must be trebly thanked. The Reps translation, after all, was written for a general audience, not the specialist, and was a pioneering effort that engendered the English-speaking world's immense interest in the tradition, with many wending their way to Kashmir to find out more.

Divine Awareness (the Bhairava state), is simply oneself, one's consciousness, not as Thinker, but as Knower.

Again, if we are seeking to Know something, we must remember nothing can become the Known, without the Knower.

Because one's Divine Awareness lies beyond thinking, that awareness is immune to what one thinks about it.

There is no object to be known.

This "terrible medicine," as Swamiji deems it, is learning that we have nothing to do.

The medicine is terrible because, for most people, doing nothing is exceedingly difficult.

For instance, in this particular presentation of the scripture, the scripture's third mode of meditation, "Meditation 3," provides us with the scripture's first instance of a less-is-more, Shambav-upaya verse:

When the mind is silent and breath ceases to flow in and out, of its own accord it stays in the centre.

When most people sit quietly and close their eyes, however, their breathing does not still into quiescence but continues flowing inward and outward. The mind continues streaming thoughts.

For such seekers, Swamiji would probably prescribe a more process-oriented method.

For the nun William Wordsworth had in mind when he wrote the holy time is quiet as a nun breathless with adoration, Swamiji would most probably recognize that she is spontaneously on the right track and encourage her to continue.

As the scripture points out, one way of meditating is simply to do so on whatever brings one peace. Swamiji elaborates, saying that if one feels at peace in the garden, then going into the meditation room would be a sin.

In Kashmir Shaivism: An Exposition, Swamiji describes the role of these 112 methods as follows:

Any method, however subtle, can be only a result of a thought process—a product of mind. Hence it cannot touch that which is beyond thought, beyond mind. The mind can penetrate, at best, up to its own frontiers. Do what it will, it cannot go beyond its limits of time and space . . . A method implies duality—a seeker and an object of search, a devotee and an object of devotion. The ever-present, all-pervading, all-knowing Totality needs not to be beseeched or coaxed. It arrives unsought, like a fresh breeze from the mountaintop, when the mind is free from thought and seeking.

When an aspirant comes to the clear realization of this fact, the Shambhav-upaya (the method of Divine Will) becomes An-upaya (No-Method) or what may be translated as Beyond-Method. In this state of non-dependence and effortless awareness, there is neither acceptance nor rejection, neither justification for nor identification with any feeling or thought. In this void, the worshipper is the worshipped. This state is not beyond action and wisdom only, but beyond will, too. It simply is.

Knowing this—is the medicine that is difficult swallow.

So, as Swamiji teaches, this motherly scripture offers some sweets, some compensatory doings—some spiritual fiddleings, a suite of finite infinities.

The hope is that these sweets will gently, subtly wean one off of constantly doing and thinking and into the throbbing stillness of the embrace of Being.

Not that Mother intends for us to swallow her entire bowlful of sweets. One or two will do!

One good place to start is Chapter 2 of Self Realization in Kashmir Shaivism, entitled "Talks on Practice."

Aeons ago . . .

. . . in the mountain vale of Kashmir . . .

in the effortless ways lakes

reflect night's flow of galaxies . . .

a procession of yogic subtleties appeared.

These subtleties are not solid, stolid, mapped-out mental expositions.

They point not to concepts.

For they are She . . .

She Herself . . .

the Creatrix of the galaxies.

She

is not an unyielding,

orthodox, dogmatic,

eyes-clapped-shut mental being.

She

is not a building up,

like the erection of a theological system.

She

is Shorelessness . . .

a licking away . . . a melting . . .

a lingo of erosion.

Or snow-blindness . . .

bleaching away one's vision

of this world.

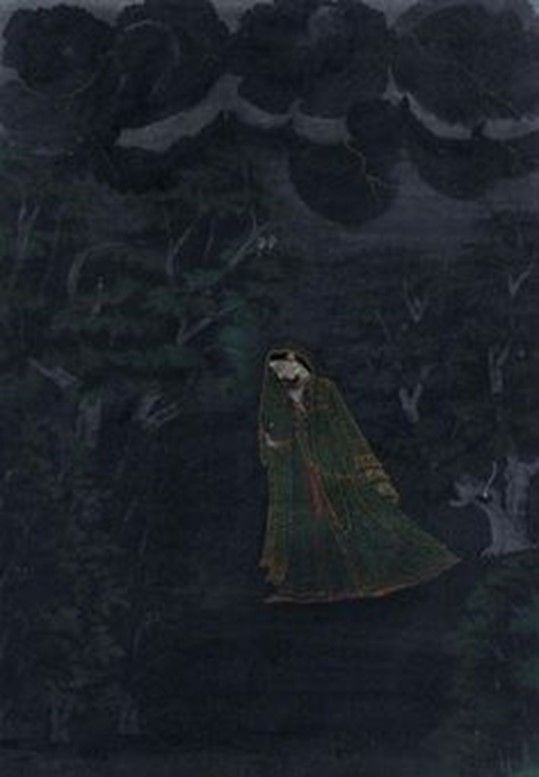

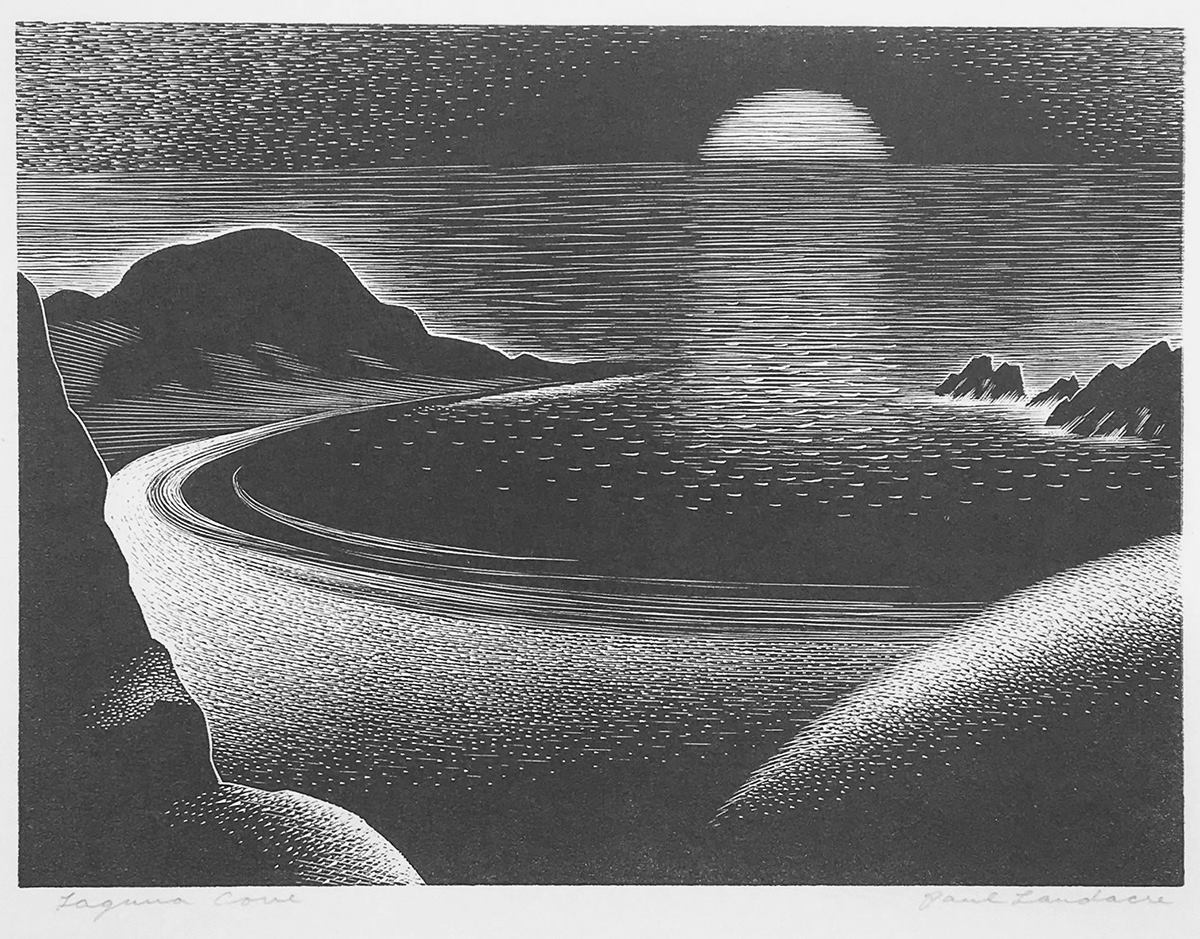

She

might be monsoon darkness . . .

eroding away forms

into a sable state

of shoreless union.

Her

roots do not fail . . .

for she is fast-rooted . . .

a dancing tree . . .

a yoga anchored neither in Sky

nor Earth

but in precisely no place

in particular . . .

dancing as

each truly living moment

of one's life:

a djinn

a genie flailing rhapsodically

her thousand-thousand arms,

pounding out silent rhythms

at full-universe scale.

A magician . . .

She

offers high-wattage . . .

fun . . . unfussy . . .

vertiginously alluring

gardens

of awe . . .

She

perceives the world

not as solid

but as a web

woven

of wonderments . . .

of breathtaking

astonishment . . .

delight swooning,

flickering, fading,

dissolving, evanescing,

into awakening.

She

teases forth

our sensitivities

to spirit-like impalpabilities . . .

ephemerealms . . .

She

beckons . . .

from within

the dark voids within

water pots

village wells,

the silence-haunted

tones

of the syllables we intone . . .

from the nothingness

indwelling

unending spaciousness

of blue sky . . . of

all-absorbing darkness . . .

of silences

before and after

lightnings . . .

from the black emptiness

within

the circles of peacock feathers . . .

from the boundless space

within

the heart . . .

from the gaps between

inhalation

and exhalation . . .

waves of mind

and their troughs,

before and after notes

of melody

as they fade

into nothingness . . .

before and after intense delight

and astonishment . . .

when being tickled . . .

and loved . . .

remembering

such joys . . .

or the warmth of reunions . . .

or when immersed

within sounds

of misty waterfalls

or rapid-running,

thunderous

rivers . . .

as waking fades

into sleeping . . .

the inner eye of bliss . . .

opens

or

when swaying

side to side . . .

bouncing up

and down . . .

when gazing

into void . . .

before and after

a bee’s prick . . .

before

and after desire . . .

when awed

by a magician’s trick . . .

at the beginning

and end

of sneezing,

sorrow

sighing,

keen curiosity

or hunger . . .

or when

intense devotion

melts

into union . . .

when confounded

by a puzzle

or aporia

'till mind

gives up

and reposes in silence . . .

Within each fading

away . . .

indwelling

each

of these unknowings . . .

struggling not

to refill

the veiled moon

with light

but

like darkly

turbulent

convolutions

of monsoon clouds

bleeding

into midnight's

layered veils, a blackness

fractured and interlaced

with deep, golden veins of electrified

now-ness.

Unknowing

being

a kind of monsoon cloud

an opening

to eternities

like a magician's

pauses —

wand poised

above

ephemeral

peanut

shell —

neither common legume

nor coin,

disclosing . . .

but

nothingness

poised

within all points

of all eternity’s

wondrous hatching . . .

For at Her best,

She

is neither stolid nor stonelike

but impish,

nymph-ish . . .

creation

in mid-chaos

and chaste stillness:

one more impasse

one more bloom

of lotus scented

with inaudible thunder

seeking ever new points

of suspension,

a yoga

of unknowing . . .

a certain negative

capability,

a capacity for drifting

within

the thin aether

of obscurities

uncertainties

riddles

aporiae

mysteries

doubts

near-nothings

fading away . . .

without grasping

after facts

and reasons.

She . . .

a yoga of voids . . .

of absences . . . blooming

up

between

the cracks

between tones

breaths

moods

moments

sips

states of consciousness

kisses

modes of being

ripplings of light

across the space of the heart . . .

between the patterns

of lisping patters

of rain . . .

with peacocks

piping

pea-pea pew-pew-pew

amid amorous effluvia

of monsoon downpours . . .

monsoon blackness

forever moving

folding over

within

her own utter

penetralia —

with pauses

within

her misty figurations —

dramatic

fractured

with fissures

lightning gasps

inter-undulatory naughts

abysses

ever-roiling within

convolutions

of awareness.

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

Gaze

a few minutes . . .

into the triatic thundercloud’s convolutions, do you notice how haunting, how ghost-like figurations of presence, ever shifting — arise? How "they" "present" "themselves" as erasings of all former "presences," while dissolving, as fresh new forms float into vision? How each so-called cloud depends upon and bears within Her forms the traces of past and future clouds? How — as soon as there “is” some “thing” to see "there," "it" will have always already been swallowed? How there will never have been any central configuration of roiling cloud that could be inked in with a capital C ?

How the only real presence — fleeting, among all these enfoldings, billowing fading convolutions, pauses between waves — is pure, vibratory awareness — flashing?

How you assume a body of steam, a face of mist, a crown of unhurried lightning, crossing this cloudbank . . . entering this pause . . . ?

How — floating, frolicking, leaping between undulations — awareness swallows Herself . . . an ephemeral fish . . .

Gazing again . . . do you notice how . . . the less you grasp at these billowings . . . these fade-ings . . . surrendering to their flow . . . how they rise and mist away . . . how fissures loom and flash forth within larger swallowings . . . formless, luminous, weightless?

Awareness . . . a fish leaping among the green body of river reeds, a poetics of mute thunder melting into the penumbra of a voiceless, formless silence, a Goddess of silence-haunted syllables, Her toes curling into rain, Her fingers entwined within your own.

As lightning . . . She appears from within clouds . . . rain borne . . . clothed in rain . . . leaping from fire to formlessness . . . within the central channel . . .

A gardenia hidden within cascading ebony tresses . . . Her eyes of rain . . . Her waist of water . . . Her embrace a current . . . She rushes into river . . . floating away . . . one night, O human child, with your heart . . .

To find Her — a thousand years ago — hugging the Malabar Coast . . . lustrous, fresh-blossoming . . . sandbanks white with masses of pearls scattered “there” by incessant waves . . .

Sailing upcoast, lustrous, naïve young women lift up their questioning faces . . . their rapt eyes . . . draining deep draughts from your heart.

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

When cool, moisture-laden winds gush through your tresses . . . sky darkens to peacock feather pitch . . . when solid sheets of water flood from sable, seething clouds . . . when the universe of vegetation sways and writhes in plundering embraces of monsoon winds . . . when lovers dip their quills . . . their hearts bleeding inky love notes . . . as amorous cumulonimbi melt into one another in tumbling poesies of yearning . . .

As sunless daylight sinks into moonless night . . . maidens burn jasmine incense sticks which — dying — continue raising their ash-soft necks to humid kisses of night air.

Abandoned to monsoon darkness . . . to world-swallowing night . . . to black thick enough to touch — these maidens wonder . . .

Has the broad shadow of the body of some Divinity erased the world?

Has the sky, its soft . . . thundering folds . . . swallowed Earth with all her seas and mountains?

Fawn eyed . . . beholding only blackness . . . draped in sable silk . . . bodies scented with sandal and musk . . . necks agleam with black sapphire necklaces . . . ears dangling ebony peacock feathers, they steal away to their secret rendezvous.

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼