Reflections

Dear All,

My name is Jim Powell.

My purpose here is to share with you 112 finite infinities as presented in the verses of an ancient Kashmiri scripture.

Kashmir, having been a tributary of that current of cultural exchange known as the Silk Road, was exposed to an array of meditation traditions: from Siberian shamanism to Indian modalities to philosophical currents from as far afield as the Mediterranean seaboard.

These techniques have been boiled down to descriptions of two stanzas, with any technical details left to oral, master-to-student transmission.

The scripture is known as the Vijñāna Bhairava, and the translation (from Sanskrit into English) was a gift of Swami Lakshmanjoo and one of his Kashmiri friends, Pandit Dina Nath Muju.

Let me tell you how it came about that a highly revered Kashmiri saint came to disclose a sliver of his native land's teachings to a faraway Santa Barbarian.

The answer is that I'm not sure I know.

I attribute the gift, though, to Swami Lakshmanjoo's wish to share his tradition's knowledge.

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

By 1975, when I received Swamiji and Panditji's written teachings on Kashmir Shaivism, I had already been meditating one-pointedly for some seven years and was awed and thankful for the absolutely effortless unfoldings within my heart.

As with all my many meditating friends, I began to notice we would transcend not only during meditation but that the transcendental state began accompanying us more and more, holding hands with us even as we stepped forth into activity.

Thus, we began to recognize with increasing clarity and to infuse into our daily (and nightly) lives this major fourth state of consciousness underlying the waking, deep sleep, and dream states. Consequently, our lives became increasingly serene and dynamic.

For us, many common, quiet activities had become finite infinities:

While lying on the back and gazing into the depths of an azure sky; when surrounded by darkness; when lying abed and drifting into sleep, with the twilight of the waking state fading into shoreless awareness; and during other moments, many of them recognized in the verses of the scripture: the Vijñāna Bhairava.

After all, one of the scripture's all-embracing meta-verses teaches that one can abide as Divine Awareness wherever and whenever one feels peace.

Because consciousness reigns everywhere, in every point of perception. And one can recognize Shoreless Awareness in its pure state everywhere and anywhere.

What is ultimately significant, right here, is present everywhere.

So, in varying degrees, pure awareness spontaneously began abiding within us as our fundamental identity, even during activity: just as yellow dye will permeate and color a cloth that has been repeatedly dipped within its fluid body.

This proved to us another fundamental point, one which Lakshmanjoo emphasizes in his Exposition on his tradition: that each one of the methods of diving into the field of lively pure awareness, the field of pure creative intelligence, yields the fruit of all the other methods in the Vijñāna Bhairava.

Although Pandit Dina Nath Muju wrote that the translation would be ready in a fortnight, it took some five months: which implies a rate of a little less than one verse per day.

Swamiji and Panditji accomplished this on top of all of their numerous other activities. For instance, Panditji was an educator, and his sweet wife and lifelong companion was blind.

Pandit Muju explained that to discuss the translations, he met with Lakshmanjoo when he could, usually once per week.

I hope some will find this work to be of interest. May it shed light on some of Swamiji's as well as Panditji's other publications as well as on their enthusiasm in responding to serious inquiries of those from various walks of life.

Among Swamiji's teachings, The Manual for Self-Realization: 112 Meditations of the Vijñāna Bhairava Tantra (edited by John Hughes), is a treasure.

In the manual, Swamiji comments on each verse, often translating word for word, mostly he responds to questions from his students.

When reading these conversations, one becomes aware that when one translates texts such as this, one is, as if across a wide river, attempting to carry across the uniquely and infinitely inter-echoing intricacies of an entire culture into another.

Yet the meaning of the scripture abides beyond words.

Swamiji explains it this way: The methods described in these verses are like the sweets a loving mother spoons into her child's mouth to help the medicine go down.

We may ask ourselves: What is this medicine?

This "terrible medicine," as Swamiji characterizes it, is fundamental.

The medicine is simply the difficulty of knowing that the meaning of the scripture, Divine Awareness, is not an object to be known.

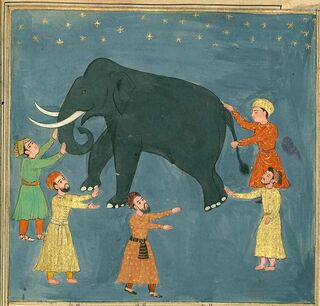

Any mind attempting to know Divine Awareness mentally will, like a blind man seeking to know what he is touching, merely continue circling the elephant.

If Divine Awareness is not an object that can be known, what is it?

Divine Awareness (the Bhairava state), is simply one's shoreless ocean of consciousness, not as Thinker, not as the Known, but as the Knower.

If we are seeking to Know something, we must remember nothing can become Known, without the Knower.

So the first order of the day is to recognize oneself as Knower, the One Unbounded Ocean of Consciousness.

There is nothing one can do to know what one already is.

Because one's Divine Awareness lies beyond thinking, that awareness is immune to what one thinks about it.

The Goddess, who at the scripture's very beginning confesses her inability to get to the essence of the tradition, demonstrates that she had assiduously studied its teachings.

Although her mind could not get to the meaning of the teachings, she still wants to know! She remains lively with curiosity.

Her response is then simply to give up!

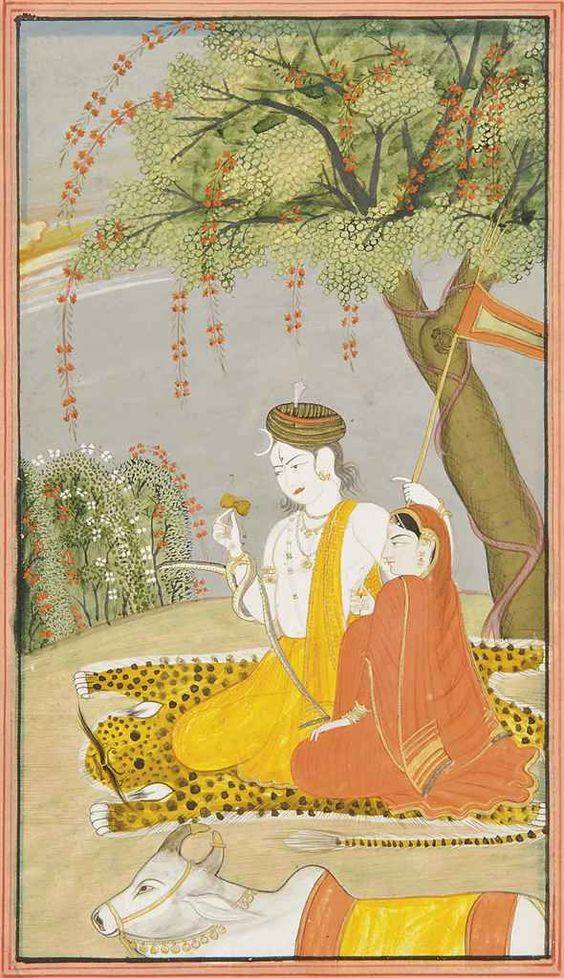

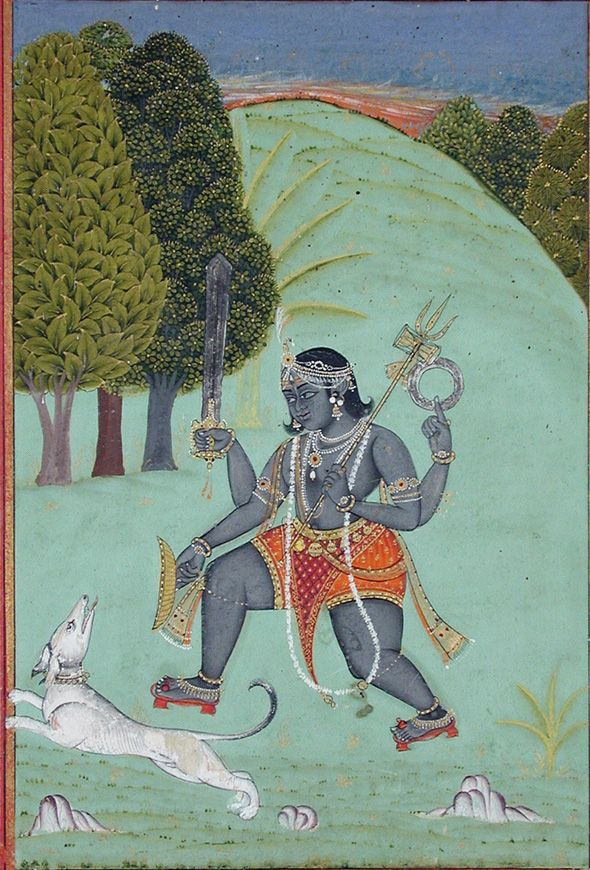

And to submit a plea to the very embodiment of calm and shoreless consciousness: her consort, the God Bhairava, who thus begins uninterruptedly detailing all the scripture's techniques.

Some readers attentive to the Goddess's mental state may notice that Verse 112 of the scripture explains her state precisely: Although her mind has not yet been able to grasp the essence of the tradition's teachings – her mind remains afloat within its own aether of curiosity, of unknowing.

Then her mind ceases to function.

For the duration of dozens of verses, her mind, showing no evidence of activity, remains silent.

When the mind remains completely still, however, its thought structures have evaporated.

It is as though the quiescent God and the lively Goddess have reversed roles.

Suddenly, for the Goddess, there is nothing circling the elephant of Shoreless Awareness!

According to Verse 112 of the scripture, it is precisely at such moments of mental impasse that one's own awareness abides as Divine Awareness: beyond thought constructs, fully enjoying the fruit of all the 112 methods.

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

Religious Studies is not an autonomous discipline but draws upon other fields: anthropology, philology, linguistics, history, sociology, psychology, art, theology, semiotics, literary theory, music, and their deconstructions.

Sociologists, anthropologists, and psychologists of religions may engage in research of the social structures underlying a scripture's mythological structures, including their theologically implied portrayals of gender relations.

Thus, if the scripture has one axis connecting itself with the reader, it has another connecting itself with a field of other texts.

These might include texts within the scripture's own genre as well as texts within the scripture's general cultural milieu, and beyond.

For instance, some Kashmiri texts of the era mention the limited freedoms and opportunities Kashmiri women of the Medieval era enjoyed, and some scholars surmise that the text may have likely been written by a woman.

If so, did the Goddess face the same types of gender-related challenges the famous Kashmiri poet and mystic Lalleshwari confronted a few centuries later?

Viewed dualistically, on the surface, narrative level of the text, we have a God, Bhairava, displaying his understanding of a tradition he embodies. In fact, he is thought to abide as the very essence of the tradition, with his discourse occupying most of the scripture.

As mentioned, we also have a Goddess, Bhairavi, his consort, who claims not to grasp the essence of the tradition's writings.

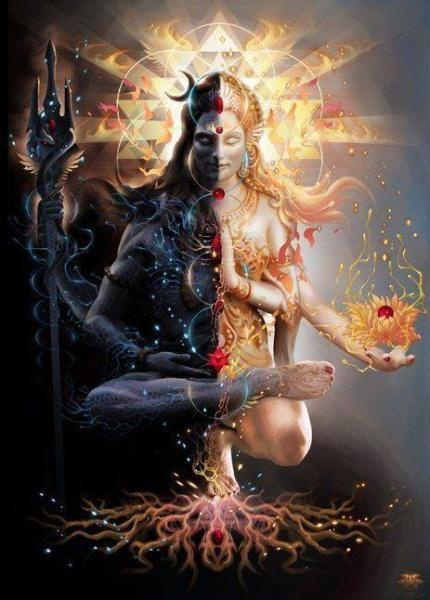

Viewed in a non-dual mode, however, these two mythic figures of that era represent two aspects of one Divine reality: the God being the quiescent ocean of Shoreless Awareness and the Goddess the Creative Waves embodying that pure Mass of Knowingness.

When at the beginning of the scripture, the Goddess becomes fruitlessly exhausted in her attempts to think her way into the essence of what she sees as her objects of study – she simply gives up.

It is only after having given up, though, that she announces her state of unknowing, of having exhausted what she had considered to be her only viable route to knowledge: the mind.

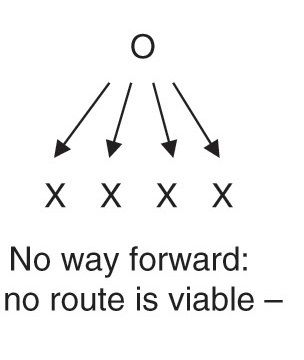

She had, in the process, reached a state of mental impasse, of seeing no forward path: an aporia. A pathless path.

Astute readers may notice that the numeral of Verse 112 is identical to the number of the scripture's many ways (112), most of which Lakshmanjoo illuminates in his commentary.

Verse 112 informs us that a mental impasse can act as a path leading to the realization of Divine Awareness.

Verse 112 teaches that when one lacks the ability to mentally grasp an object of knowledge, the mind, in giving up, may dissolve into Divine Awareness.

Some readers may have concluded that having found herself out of her own depth and having given up mentally, the Goddess's awareness must have, as the scripture itself describes, silently, subtly subsided into its own boundless self-referral state.

As Lakshmanjoo has pointed out in his commentary, this can happen when the mind gives up trying to comprehend the Object of Knowledge and dissolves into the Shoreless Awareness of the Knower.

Aporiae (the plural of aporia) are often followed by illumination.

Has the God even noticed that the Goddess – in giving up – has already, as per Verses 112 & 127, gone beyond thought, and thus fulfilled the aim of each of the 112 methods the God is about to describe to her?

Is the female half of the Divine Dyad only feigning ignorance? After all, the God, her other half, is eternally one with her, so "his" presentation of the means of abiding as Divine Awareness, is also "hers."

Switching back to a dualistic perspective, if he did not notice her state, it may be because the divinity of her unknowing state is merely implied. Though she admits she cannot get to the essence of the tradition, the scripture merely implies that she has in fact gotten to the essence, as a result of her mental impasse, by going beyond mind.

The scripture "tells" it "slant," to place it within Emily Dickinson's parlance.

Though the scripture may have been written in the 7th or the 8th century, it was not until the 9th that Ānandavardhana, in his Light on Suggestion (or Implication), revolutionized Indian poetics with his insights into innuendo.

[A brief lesson on implication: When a woman asks her beloved if s/he feels a draft in the room, the meaning of the question is often not what the words actually denote on a word-by-word basis. It is not even a question. It is an imperative sentence. The meaning of the sentence is something like the following: "Honey, please get up and shut the window." ]

Even before implication and suggestion had become officially and theoretically elaborated in India, scriptures and other writings were quietly overflowing with gender-related innuendo and implication.

After all, often unnoticed, women, moonily amusing themselves within the relative obscurity of their creative grottos, have often secretly revolutionized their fields of endeavor.

One good example is the Swedish artist and mystic Hilma of Klint (1862 – 1944) a revolutionary whose phospheme-like paintings have only recently been recognized as among the first abstract works in the history of Western art.

Much of her collection predates the paintings of the male artists credited as the originators of the movement – Kandinsky, Malevich, Mondrian.

Similarly, although men got credit for first walking on the moon, it was an unsung, unassuming female computer programmer, Margaret Hamilton, who actually had the "right stuff" to write the code that actually got those men to the moon and back – with nary a software glitch on any of the Apollo missions!

If the Vijñāna Bhairava was written by a woman, it should not surprise us if its quiet and gentle gender innuendos ventured beyond mere metaphor to pioneer powers of the written word that did not begin to frequent male-dominated Sanskrits until centuries later, when innuendo and implication formed a new dimension in Sanskrit verse.

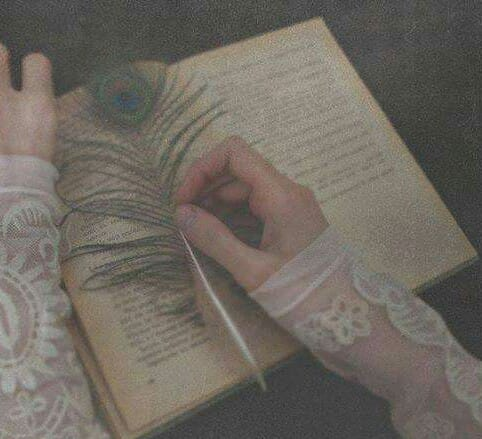

The God, on the other hand, unfolds his array of meditation techniques like a courting peacock unfolding his tail feathers.

In fact, this image of the peacock is one of the most enduring images in the Indian subcontinent.

In Biblical times, King Solomon imported a peacock from India, all the way to Egypt. And when the Queen of Sheba visited him, she brought along her own peafowl.

Peacock courtship eventually developed into one of the most common tropes of romantic Indian monsoon poetry.

From the sastras, we learn that the Divine form presiding over grammar is seated on a peacock and that the thirty-two forms of Sakti corresponding with the thirty-two forms of Aghora Murti (a form of Siva) have as their vehicle the peacock.

The Siddhasabara Tantra describes beings presiding over the letters ai, o, na, and dita as being seated on a peacock.

And so, take note of how, when the Goddess of the scripture confesses her inability to grasp the essence of the philosophies of the tradition intellectually, the God of the scripture, as in the mating dance of a strutting peacock, begins spreading out his array of "feathers": his scintillating rainbow of mystic "eyes" reaching into infinities: each revealing to the Goddess a method of realizing union within the quiescent aspect of him-her-self.

As we have seen, Verse 112 of the scripture is one "feather" focusing on mental impasse.

Another one of the verses, another one of the "feathers," Verse 36, actually focuses on a peacock feather.

Is the creator of the scripture here gliding from mere implication into brazen hint?

After all, consider the following: in objective reality, peacocks dance before peahens by splaying out their tailfeathers, about 150 of them. (About the same number as actionable, method-related verses in the scripture.)

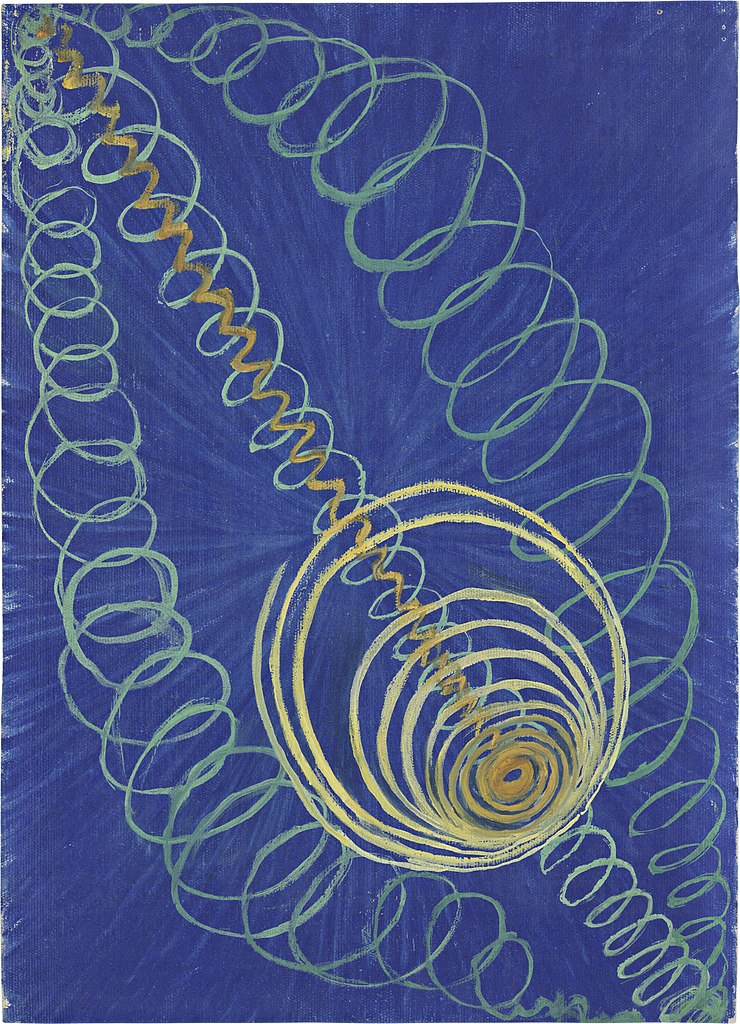

Among peacocks, the display is vibratory.

As the male dances, his feathers hum along at twenty-five cycles per second, causing the "eyes" of the feathers to appear as if hovering in space.

Scientists have recently discovered that, according to the laws of physics, the finer and more feminine feathers adorning the crowns of the peahens' heads then begin to entrain vibrationally, in unison with the male's tail feathers.

This humming often results in the conception of baby peafowl. And, as the tradition suggests in explaining the relationship between consciousness and its infinitely diverse expressions: all the resplendent iridescence of the peacock's tail feathers is present in nascent form within the yellow yolk of the peahen's egg.

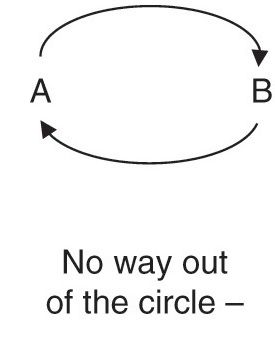

One kind of paradox that can lead to a mental impasse, and then illumination, is circular.

For instance: the relationship between consciousness and its expressions, as well as the two-in-one relationship between Bhairava–Bhairavi are mirrored in the logic of a paradox formulated by the Indian grammarian Bhartṛhari.

Though the paradox is only one statement, it eternally vibrates back and forth between two semantic poles, giving rise to an endless interplay between two meanings.

The paradox reads as follows: Everything I say is a lie.

(Hint: If it's true it's false; if it's false it's true.)

It appears that you can't stop the paradox from oscillating, throbbing, pulsing from one meaning to the other, and then back . . .

Further, Bhartṛhari's liar's paradox brings to mind the aporia inherent in Verse 133 of the scripture: the teaching that the whole universe (including, by definition, Verse 133 and the entirety of the scripture's other verses) is a magic trick.

When flabbergasted by a magic trick, only after the astonishment fades away, does one realize it had been "only" a trick, an illusion: not at all real.

Thus, if the verse is truly a trick (untrue), it is true. If it is truly true, it is false.

In other words: If this verse on magic applies to itself, then its statement that everything is only a trick is also only a trick.

If the statement is real, it's not real. If the statement is unreal, it's real.

And if the statement applies to all the other methods in the scripture, they are all birds of the same feather, vibrating back and forth between true and false, fullness and emptiness, just like Shiva and Shakti.

Thus, the verses of the scripture pertaining to method employ a dual structure. Usually, they begin with a stanza describing graspable things of day-to-day reality (breaths, peacock feathers, monsoon nights, vast and featureless landscapes).

Then, in the second stanza, the verse will leap to the mysterious referent – Divine Awareness: the Ungraspable and Unsignifiable.

At times, the Unsignifiable is signified by the word Void (as in the eye of the peacock's feather), the Void that points to the very purpose and meaning of each verse.

No matter how deeply the scripture is devoted to the concept of a Void, however, it is not devoid of a strict compositional logic.

In fact, an adroitly evasive Void informs the structure of each of the 112 methods. For each method mirrors the semantic structure of the peacock feather verse's dance between Form and Formlessness, voluptuous imagery and Void.

Each verse of the scripture is made up of two stanzas. The structure of each actional verse in the scripture is that of a peacock feather: (a) the quill and sub-feathers are analogous to the signifiable method of the first stanza and these lead to (b) an absent-to-the-seeker, unsignifiable Divinine State, as mentioned in the second stanza.

Breathing, imagining, sneezing, contemplating, walking about: all are words that have referents in the world as we know it.

Where, however, is the referent to the expression Divine Awareness?

Seekers know only that, somehow, this elusive Divine Awareness, whatever it is, seems to be the very Meaning of every verse: indeed the Meaning of the entire scripture, and of life.

Thus, if we truly knew ourselves as Divine Awareness, we would feel no need to be to study the scripture and practice its methods.

This brings up the question of which of the 112 methods to practice. This question, however, according to verse 132, makes up another practice of Ungraspability.

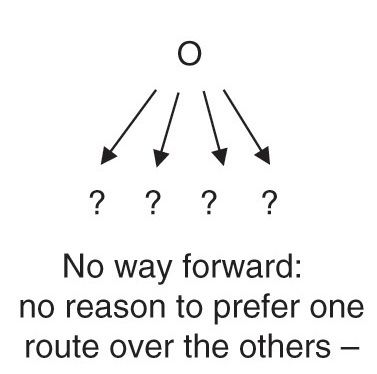

Luckily, another type of aporia arises when trapped in a paradox of choice, for instance: Which person shall I marry?

(In the above schematic representation, this type of aporia resembles an array of peacock feathers radiating from a single eye.)

And perhaps one of the most efficient and mathematically elegant ways of leaving all thought aside and residing as Shoreless Awareness would be to become so mired in indecidability that when contemplating which of the scripture's methods to adopt, one cannot decide.

Although paradox often leads the mind to a state of aporia – a felt sense that the mind realizes it has no path forward – that is a good thing.

After all, the Goddess posing as one who confesses she is not able to understand the teachings of the tradition leads to the unfolding of the 112 ways for all of us non-Goddesses.

Although all aporiae can bring about a mental impasse an aporia often precedes a sudden epistemic shift beyond mind – into spiritual illumination.

For instance, Arjuna, in the Bhagavad Gita, was considered to be India's greatest archer. Yet, all of Arjuna's knowledge of the scriptures and of dharma did not prevent his mind from falling into a state of aporia, which preceded his spiritual illumination.

His illumination unfolded on the battlefield only when he laid down his bow in the battle between his mind and heart, entering a state of pathless inaction.

Aporiae are universal. They indwell not only Shaivite dialogs but, for instance, the Socratic method, especially in Plato's early dialogs.

MENO: Socrates, I certainly used to hear, even before meeting you, that you never did anything else than exist in a state of perplexity (aporia) yourself and put others in a state of perplexity. And now you seem to be bewitching me and drugging me and simply subduing me with incantations, so that I come to be full of perplexity. And you seem to me, if it is appropriate to make something of a joke, to be altogether, both in looks and other respects, like the flat torpedo-fish (narkē, stingray) of the sea. For, indeed, it always makes anyone who approaches it grow numb, and you seem to me now to have done that very sort of thing to me, making me numb (narkan). For truly, both in soul and in mouth, I am numb and have nothing with which I can answer you. And yet thousands of times I have made a great many speeches about virtue, and before many people, and done very well, in my own opinion anyway; yet now I’m altogether unable to say what it is. And it seems to me that you are well-advised not to sail away or emigrate from here: for, if you, a foreigner in a different city, were to do this sort of thing, you would probably be arrested as a sorcerer. [Plato’s Meno 79e-80b. From the translation of Berns and Anastaplo, Focus Philosophical Library, 2004, as quoted in Woody Belangia, "The Uses of Aporia, The Torpedo Fish Analogy in Plato's Meno," on the website Shared Ignorance: Towards a Defective Reading of Plato. The uses of aporia: the torpedo-fish analogy in Plato’s Meno | shared ignorance (woodybelangia.com) ]

Aporiae also indwell the philosophical methods of thinkers such as Pyrrho, Timon, Arcesilaus, Diogenes, and Sextus Empiricus. Sextus was quite explicit about the connection between skepticism and the aporetic method, arguing that the skeptic way be embraced as a way of life (agoge) or disposition (dunamis), and that the suspension of judgment (epoché) helps us achieve inner tranquility or peace of mind (ataraxia).

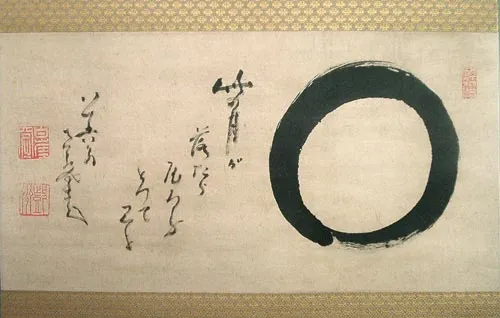

Michael Jackson explains how, in another realm, during the beginning of China's Sung dynasty, aporiae in the form of paradoxical words arose among Zen masters.

The T'ang period developed these in the koan: a mystifying puzzle forcing one to abandon mentation and open to new ways of (un)knowing – such as immediate experience.

Thus, the Goddess Bhairavi was not the only mythic female character to have experienced an aporia leading to illumination.

Another, among many such figures, was the legendary zen nun Chiyono: famous for having written the following no-nonsense poem, here pared down to its minimal core:

No water –

No moon.

The longer version involves a story:

CHIYONO [MUGAI NYODAI]

from Richard Bryan McDaniel: Zen Masters of Japan. The Second Step East. Rutland, Vermont: Tuttle Publishing, 2013.

One of Bukko’s students was the first Japanese woman to receive a certificate of inka. Her Buddhist name was Mugai Nyodai, but she is remembered by her personal name, Chiyono. She was a member of the Hojo family by marriage and a well-educated woman who long had an interest in the Dharma. After her husband died and her family responsibilities had been fulfilled, she went to study with the Chinese master. After completing her studies with Bukko, she became the founding abbess of the most important Zen temple for women in Kyoto, Keiaiji.A teaching story with no apparent basis in fact suggests that before coming to study with Bukko, Chiyono had been a servant at a small temple where three nuns practiced Buddhism and hosted evening meditation sessions for the laity. According to this story, Chiyono observed the people practicing zazen and tried to imitate their sitting in her quarters, but without any formal instruction, all she acquired for her efforts were sore knees. Finally she approached the youngest of the nuns and asked how to do zazen. The nun replied that her duty was to carry out her responsibilities to the best of her abilities. “That,” she said, “is your zazen.”Chiyono felt she was being told not to concern herself with things that were beyond her station. She continued to fulfill her daily tasks, which largely consisted of fetching firewood and hauling buckets of water. She noticed, however, that people of all classes joined the nuns during the meditation sessions; therefore, there was no reason why she, too, could not practice. This time she questioned the oldest of the nuns. This woman provided Chiyono with basic instruction, explained how to sit, place her hands, fix her eyes, and regulate her breathing.“Then, drop body and mind,” she told Chiyono. “Looking from within, inquire ‘Where is mind?’ Observing from without, ask ‘Where is mind to be found?’ Only this. As other thoughts arise, let them pass without following them and return to searching for mind.”Chiyono thanked the nun for her assistance, then lamented that her responsibilities were such that she had little time for formal meditation.“All you do can be your zazen,” the nun said, echoing what the younger nun had said earlier. “In whatever activity you find yourself, continue to inquire, ‘What is mind? Where do thoughts come from?’ When you hear someone speak, don’t focus on the words but ask, instead, ‘Who is hearing?’ When you see something, don’t focus on it, but ask yourself, ‘What is that sees?’”Chiyono committed herself to this practice day after day. Then, one evening, she was fetching water in an old pail. The bucket, held together with bamboo which had weakened over time, split as she was carrying it and the water spilled out. At that moment, Chiyono became aware.Although the story about her time as a servant is certainly apocryphal, the part about the broken pail precipitating her enlightenment seems to be based on her actual experience. She commemorated the event with these lines:

In this way and that, I tried to save the old pail since the bamboo strip was weakening and about to break until at last the bottom fell out. No more water in the pail! No more moon in the water!*

*Paul Reps, Zen Flesh, Zen Bones (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, no date), p. 31.

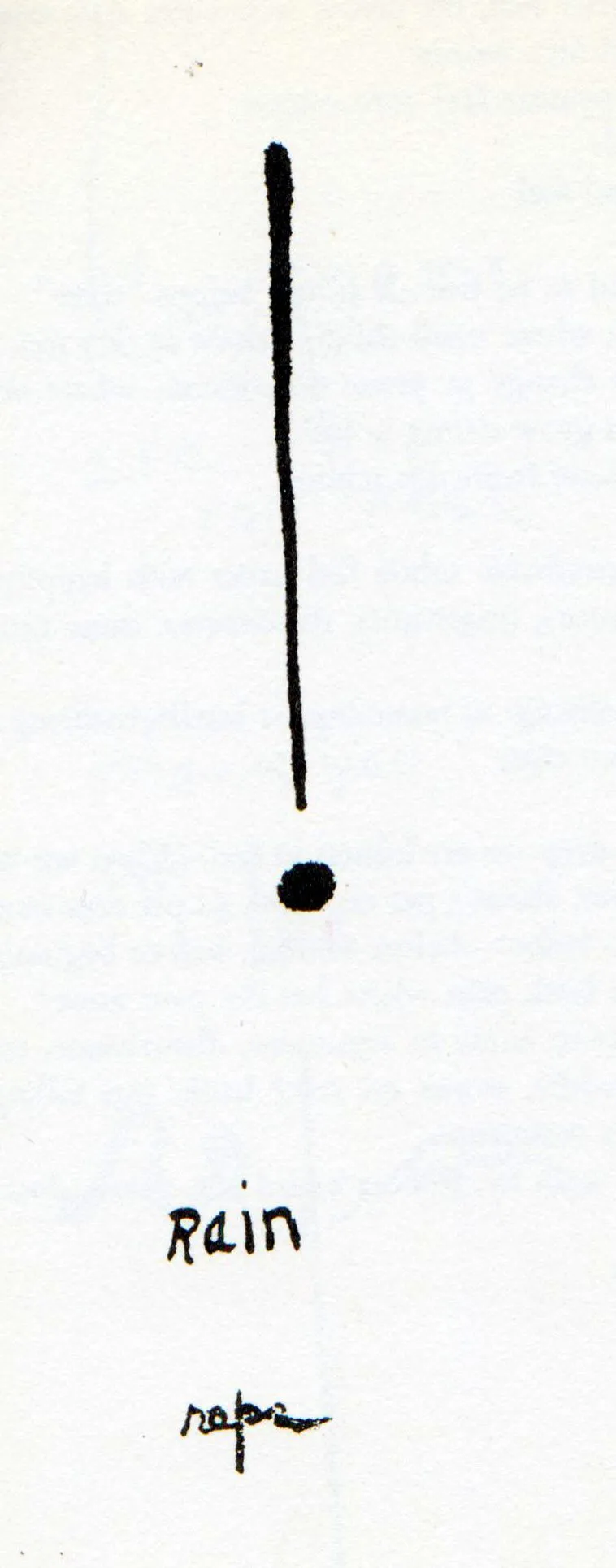

Not having been born into Sanskrit, Paul Reps may never have been able to bask in the full sunlight of the Vijñāna Bhairava.

Rather, his renderings shine like photographic film exposed to moonlight: fugitive traces of lunar atmospherics brushing up against a bare, zen-sensitized membrane.

Reps' aesthetic sensibilities, though, even though mired within his Indic linguistic limitations, have something valuable to offer.

Sitting in Kashmir with Swami Lakshmanjoo as he penned his renditions of the scripture, it would have been impossible for the poet not to have immediately recognized a structural affinity between the forms of much haiku and waka and the structure of the verses of the VBT.

I say this because almost every haiku juxtaposes – at first glance inaptly and ineptly – two contrasting poetic images.

The two images seem not to compute . . .

my head in the clouds

in the lake

. . . until they do.

The poem’s electricity happens when the lightning of awareness suddenly leaps between these two esoterically apt — but at first seemingly ill-paired — poles: like two bodies of two star-fated lovers bumping up against one another in a slightly dangerous nightclub.

Like the moment one laughs at a pun.

When we laugh at a joke based on a pun, we forget about everything, roll on the floor, and time and space sort of collapse.

(In fact, zen poets, quantum physicists, and psychologists study puns (kake kotoba 'hinge words') as Classical World (Samsara) analogs of quantum world (Nirvana) phenomena.

In this way, similarly to how the great Kashmiri thinker Abhinavagupta paired rasa aesthetics with ontology and soteriology, haiku and waka verse commonly arrive at a haiku moment: an ah moment when the difference between samsara and nirvana collapses.

Each way presented in the VBT is similarly structured, similarly endowed with two disparate images: each dawning in the sky of its own stanza, illumining its own unique semantic horizon.

First, each of the practicum verses of the scripture presents a certain means.

Second, between the two stanzas, a gap.

And only third, usually in the second stanza, a leap pointing to the projected result of that means.

The nouns and verbs in the first stanzas are empirically familiar: pots to be gazed into, inhalation, exhalation, dark nights.

The referent of the second stanza, announcing the projected result, however, usually remains unknown to most readers, or they would not be reading the scripture.

Second-stanza signifiers do not, at first, resonate with their transcendental signified.

It is because of this, that Bhartṛhari's issue of nameability, of signifiability, arises.

The words Divine Awareness do not deliver Divine Awareness.

Until they do.

In this way, the semantic language game of the first stanza collapses in that of the second: consciousness endlessly playing hide and seek with itself.

Thus, the aporia. The mental impasse. Is the path of this magic.

Reps at times pares down the second stanza to a Japanese sense of the minimal: most notably when using a single aporetic tease word to utter what cannot really be named or signified.

Reps realizes, like Patanjali and the Sanskrit grammarian Bhartṛhari, that minimalism rests lightly on the mind, more effortlessly conveying the meaning-whole of a verse.

Many readers realize that neither haiku nor the verses of the VBT are really about the words on the page. They are about the meaning of meaning.

Those black marks are scars of spiritual-aesthetic lightning.

Both in Abhinavagupta’s poetics and in the zen-inspired haiku poetics informing the Reps renderings, aesthetic experience can act analogously to unitive spiritual realization.

The flash of a haiku’s aha moment can be so vertiginously alluring, so suddenly illuminative and unitive that it flashes forth in the formless form of a mini-realization: a little piece of Samsara suddenly recognized as Nirvana, the realms of Classical Physics and Quantum Physics, as one. This is why some types of haiku use kake kotoba, hinge words (puns).

Structurally considered, then, much haiku and many of the VBT verses are founded on a similar aporetic compositional logic.

This aporetic structure primes the reader's mind to receive, recognize, and be these sudden, unexpected, illuminative flashes of awareness.

Consciousness, being both quiescent and dynamic, purely intelligent and dynamically creative, operates as something of a self-referential ruse – just like the waves in the ocean, which never cease being ocean.

Because Bhairava and Bhairavi are actually one, the Goddess's feigned ignorance and their ensuing dialog are (Rudric) ruses as well. Bhairavi moves the aporia from the realm of the verses to the realm of the scripture as a whole.

That mystery between unity and diversity is where the magic resides. Om is where the art is.

It is likely that Reps, with his background in zen, at times attempted to skew his VBT versions in the direction of the school of sudden enlightenment.

In Shiva’s capacious triadic heart, enthusiasts such as Reps (and others) must be trebly thanked. The Reps translation, after all, was written for a general audience, not the specialist, and was a pioneering effort that engendered the world's immense interest in the tradition, with many wending their way to Kashmir to find out more.

Divine Awareness (the Bhairava state), is simply oneself, one's consciousness, not as Thinker, but as Knower.

If we are seeking to Know something, we must remember nothing can become the Known, without the Knower.

So, again, the first order of the day is to recognize oneself as Knower.

There is nothing one can do to know what one already is.

Because one's Divine Awareness lies beyond thinking, that awareness is immune to what one thinks about it.

To reiterate yet again this fundamental point: the practicum verses are generally divided into two parts: a how-to statement (for instance, Do this or that), and a statement of the predicted result (for instance, Bhairava appears). The entire object-dependent semantics of the how-to statements collapses in the result statements.

There is no object.

This "terrible medicine," as Swamiji deems it, is learning that we have nothing to do.

The medicine is terrible because, for most people, doing nothing is exceedingly difficult.

For instance, in this particular presentation of the scripture, the scripture's third mode of meditation, "Meditation 3," provides us with the scripture's first instance of a less-is-more, Shambav-upaya verse:

When the mind is silent and breath ceases to flow in and out, of its own accord, it stays in the centre.

When most people sit quietly and close their eyes, however, their breathing does not still into quiescence but continues flowing inward and outward. The mind continues streaming thoughts.

For such seekers, Swamiji would probably prescribe a more process-oriented method.

For the nun William Wordsworth had in mind when he wrote The holy time is quiet as a nun breathless with adoration, Swamiji would most probably recognize that she is spontaneously on the right track and encourage her to continue.

As the scripture points out, one way of meditating is simply to do so on whatever brings one peace. Swamiji elaborates, saying that if one feels at peace in the garden, then going into the meditation room would be a sin.

In Kashmir Shaivism: An Exposition, Swamiji describes the role of these 112 methods as follows:

Any method, however subtle, can be only a result of a thought process—a product of mind. Hence it cannot touch that which is beyond thought, beyond mind. The mind can penetrate, at best, up to its own frontiers. Do what it will, it cannot go beyond its limits of time and space . . . A method implies duality—a seeker and an object of search, a devotee and an object of devotion. The ever-present, all-pervading, all-knowing Totality needs not to be beseeched or coaxed. It arrives unsought, like a fresh breeze from the mountaintop, when the mind is free from thought and seeking.

When an aspirant comes to the clear realization of this fact, the Shambhav-upaya (the method of Divine Will) becomes An-upaya (No-Method) or what may be translated as Beyond-Method. In this state of non-dependence and effortless awareness, there is neither acceptance nor rejection, neither justification for nor identification with any feeling or thought. In this void, the worshipper is the worshipped. This state is not beyond action and wisdom only, but beyond will, too. It simply is.

Knowing this—is the medicine that is difficult swallow.

So, as Swamiji teaches, this motherly scripture offers some sweets, some compensatory doings—some spiritual fiddlings, a suite of finite infinities.

The hope is that these sweets will gently, subtly wean one off of constantly doing and thinking and into the throbbing stillness of the embrace of Being.

Not that Mother intends for us to swallow her entire bowlful of sweets. One or two will do!

One good place to start is Chapter 2 of Self Realization in Kashmir Shaivism, entitled "Talks on Practice."

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

One of the fundamental laws of nature is the Principle of Minimal Action. This law applies to light, gravity, the motions of the stars and galaxies and planets, and so to apples and cherries and water, and so on . . . to quantum mechanics, and also to meditation and prayer.

Teresa of Avila spoke of the Prayer of Quiet, during which the "Mother's milk" of Divine Love flows effortlessly into the infant's lips without any need for the child to move them.

Within the supreme quiescence of this stage of prayer, the saint suggests that simply one small syllable of suppliance, dissolving into Silence, is sufficient—from time to time—to ensure the stream's flow.

Similarly, as probably one the most love-struck aficionados of this particular and some of its sibling scriptures, the often motherly Christopher Wallis quotes a scripture beautifully describing how quietly savoring even one bite of ice cream, slowly melting away on one's tongue, may wean one away from overdoing — as in the effortlessness of falling awake.

Before beginning with these treats, though, I hope all will pause to realize that the Introduction to The Manual for Self-Reliazation is essential reading.

It is not a good idea to blithely skip over the scripture's Introduction simply because it is so humbly titled. It would be more aptly entitled as Foundational Knowledge.

When exploring The Manual for Self-Realization, it is equally important not to simply skip forward to the methods, the dhāraṇās. After mastering the Introduction, it is best to first read thoroughly and internalize verses 1 through 23. If one feels one does not understand them completely, reading them again will prove fruitful. Eventually, everything will fall into place.

Absorbing this foundational knowledge will guide one surely within, recognizing own's awareness as pure and shoreless.

As if the Sea should part

And show a further Sea—

And that—a further—and the Three

But a presumption be—

Of Periods of Seas—

Unvisited of Shores—

Themselves the Verge of Seas to be—

Eternity—is Those—

emily dickinson

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

An autobiographical note –

At the time I learned of the scripture, I was studying at the Santa Barbara campus of the University of California. My focus was religious literature in Sanskrit, and I eventually received a master's degree. My Sanskrit teachers were Nandini Iyer and Gerald Larson.

On the first day of Sanskrit class, Nandini, mother of travel writer Pico Iyer (Video Night in Kathmandu et al.) had just taken attendance, when Gerry Larson, who would begin teaching us at the start of our second year, popped his head in the door and barked out two words: Sarvam dukham! (All is suffering).

Well, first things first, I thought.

Next, it was Nandini's turn.

She gentled down the still-startled class by assuring us there are two ways to learn Sanskrit. The mind-centered way, which is what we would be doing, and the other way, which entails praying until the Goddess of Speech and Learning takes up residence upon one's tongue.

Our first night of homework was to learn the Sanskrit alphabet.

So much for the easy way, I thought.

I skipped ahead, grabbed some Sanskrit words from later chapters, and pieced together a poem for Nandini.

A couple of years earlier, she had bought a wind chime from me that I'd fashioned from large sections of bamboo. She lived high in the hills above Santa Barbara, which overlooked, dizzyingly below, the Pacific.

She would rise early, and as the chimes began to swing gently in the offshore breeze, she would take in the tones of dawn's luminous conversations with the sea.

From deep within herself, the words Apam Napat would surface: Child of the Waters.

While attending UCSB, I was also living and working and meditating in a somewhat parallel universe: the nearby campus of Maharishi International University (MIU).

I could not help but notice a stark contrast in the educational philosophies of the two organizations. Whereas UCSB students were assumed to be something akin to bottles into which disparate thoughts are to be stuffed, and the more the merrier, at MIU, education was based on consciousness rather than on thought.

One's real grade was one's radiance.

At UCSB, the foundation of the curriculum was the diversity of things Known.

At MIU, the emphasis was on the unity of Knower, Knowing, and Known: the reality of pure, unbounded awareness.

Any campus, however, will remain remiss if it serves only as a temple to the rational mind: with no rites of passage towards a more unifying field of Knowing wherein knowing, known, and knower are discovered to be One.

After all, in nature, the place where we all live, unity and diversity coexist.

It follows that any education wishing responsibly to reflect reality should teach students about the unifying filed of creative intelligence indwelling universal life.

Only then will the name university resonate fully with reality. Otherwise, all learning and the various branches of knowledge will remain isolated, with credentialed "knowers" still continuing to experience themselves apart from rather than as integral parts of an intimately interwoven fabric of wholeness.

Accordingly, for weeks at a time, in addition to their academic pursuits, the students at the MIU campus would settle into eagerly anticipated group meditation retreats.

Those special months were devoted exclusively to diving deeply into the finest fabrics of the unified field of pure creative intelligence.

Known as Forest Academies, these meditative spaces in the curriculum filled the atmosphere with boundless radiance and bliss.

This bliss overspilled the MIU campus into the surrounding UCSB student community.

One result was that at UCSB, Religious Studies became the most popular and populated major.

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the founder of MIU, encouraged research on higher states of consciousness. This research includes records of typical MIU student experiences in meditation, some of which I will share with you here.

Student 1

It’s more simple than words do it justice. I realize that I had been transcendental, and it’s incredibly appealing. It only happens spontaneously. In other words, you can’t try to get there, but there is a very familiar “not trying” that makes it easy. No flowery language can adequately describe the experience: it is simple and blissful and makes me feel clean and refreshed, like after bathing in a cold lake.

Student 2

Sometimes I have this experience throughout the entire meditation and sometimes only for shorter periods during the meditation. I find it hard to explain in words. It is like total expansion, the entire universe, it has nothing to do with me specifically, it is just totality. I assume it is w/in me but it feels like I am it.

Student 3

Often I have experienced this state of silence—it is hard to recall specific moments or times because most of these times are sacred and best not analyzed or talked about, for me personally. However, this has happened to me, and it is an unbounded connection of love and devotion and oneness with everything around me—my individuality is drowned in the Ocean of God’s love.

Student 4

One of the best experiences I have is that of total comfort of the body and mind as they are wrapped together in one immovable shield of silence and peacefulness. It’s a simple anti experience, a marvelous fullness of emptiness in which the mind flattens and expands as if an invisible horizon line were passing through my temples.

Student 5

Silence opens up spontaneously. It can’t be made, only surrendered to. It’s always present and waiting for the mind to quiet down. Once a letting go happens, all is me expanding into infinity.

Student 6

There are no thoughts. My body is in complete ease and I even forget that it’s there. All my attention is in the present not in the past or future. I’m just aware, at peace—completely. When in that space of peace, I have no acknowledgment of who I am as a person. I just am.

Student 7

Once in a while I am sitting meditating and I start to realize that I cannot feel most of my body and I feel almost light—like I’m not really sitting, or not really anywhere. It seems that there is no time and I am just being and that is all there is. I kind of would want to stay there forever. I feel like I have been in that meditation room just for a session equal to that of the blink of an eye.

Student 8

I feel energized and yet extremely relaxed. So much potential energy, it is unbelievable. The world is my playground, I am silent within myself, where I sit calmly, yet I am ready to go out and act, conquer.

Student 9

I feel like—as soon as I close my eyes, something sinks inside of me, literally like I’ve dived into a pool. Often my body seems to disappear, I can’t tell what position I’m sitting in because I can’t feel any particular part of me. It’s so comfortable and rich, my body craves this feeling of openness and expansion—that’s the word I’d use, expansion.

Student 10

I feel weightless, as if myself and my surroundings have become devoid of all space/time factors. There is a nothingness, not emptiness, but a pregnant void, which both fills my being and my surrounding, until I feel like there is no differentiation between the two.

Student 11

It feels like what a section of a river would feel, if it had feelings: a realization that it is the river yet also the river is flowing through it. The only thing to do at such moments is just to experience the experience because it is really nice and you don’t desire to do anything even though it’s almost like no experience at all.

(Brown, Suaan. 2011, "Experiences of Growth of Consciousness in Undergraduate Students at Maharishi University of Management," pp. 313–340.)

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

On his Teacher Training courses in India, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the founder of MIU (Maharishi International University) and MERU (Maharishi European Research University), would often introduce his students to other masters of the same heart.

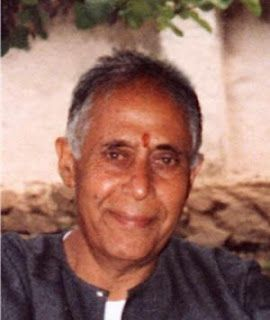

For instance, sometimes, with his newly qualified teachers, Maharishi would travel to Kashmir and meet with Swami Lakshmanjoo, pictured with him above. Both masters were enjoying life within hugely dynamic waves of oneness, Unity Consciousness.

In endearing terms, Lakshmanjoo here speaks of the unified essence of their relationship:

Lakshmanjoo

Kashmir Shaivism is exactly the truth explained by Mahesh Yogi, nothing else. It is why we have come very near, both of us [Maharishi and myself].

You will notice that Lakshmanjoo did not say that Maharishi's explanation of truth was the same as that of Kashmir Shaivism, by that the truth Maharishi living was the same.

When Lakshmanjoo learned that Maharishi would be accompanying his students on an outing, Lakshmanjoo said the following, paraphrasing a Zen teaching:

The state of samådhi is felt, it cannot be explained. You see, there were three disciples of some Saint, sometime before. And the master told them to do some practice of yoga and return after one year. And the first one returned after one year and explained to his master his experience of that one year . . . ‘in this way and that way’. And master told him, “You have realized the flesh of my body.” The next one returned after practice and explained to him in a finer way. The master in return told him, “You have got my bones of the body.” And the third one, when he returned, he remained silent before his master. And he said, “You have the marrow of my body.” So the marrow of that Transcendental Being cannot be explained in words, it can be explained in silence. In the same way, samådhi cannot be explained in words. Either it can be felt or it can be explained in silence. So it is better to remain silent.

From Lakshmanjoo's lecture in 1968.

Maharishi

Consciousness! Because it is consciousness, it is its own Knower, Known, and Knowledge – all the three are there . . . But in the nature of oneness, there is trinity [of] Knower, Known, and Knowledge . . . And this trinity and Unity, they are the same thing! But, being the same thing, it gets divided into two characters . . . So, when the trinity is predominant, then the whole dynamism, and the creativity, and the structure, and all that starts to function . . . [But] it’s the same thing – consciousness. And because it’s consciousness, it knows itself. So, there is that Knowledge-Knower-Known relationship in the structure of Unity.

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

India at that time was simpler than it is today, even though Rishikesh was not really accustomed to hosting the Beatles. Though not as quiet as it had been historically, the spiritual hamlet on the Ganges was a place where yogis could dedicate themselves to their calling. Among Maharishi's friends there was a fellow he described as being in a "good state of Unity." His name was Tat Wale Baba.

Tat Wale Baba in his cave in Rishikesh

On the altar behind Maharishi is a photo of Swami Brahmananda Saraswati, his beloved teacher.

Tat Wale Baba

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

John Hughes, pictured above with Swami Lakshmanjoo, was a grad student in the Religious Studies Department at UCSB and also taught Religious Studies at MIU.

Having traveled to Kashmir with Maharishi, John had been inspired by Swami Lakshmanjoo to continue his graduate work in Kashmir, directly under Swamiji's personal guidance. This, of course, entailed uprooting himself and his family from Maharishi International University, in Santa Barbara, and relocating to Kashmir.

Over the next several years, Swamiji worked closely with John in translating much of his knowledge into English and disseminating it as widely as possible.

Though still studying in Santa Barbara, I became interested in the Vijñāna Bhairava, which, having been translated by zen-influenced poet Paul Reps, was having its day in our Religious Studies department at UCSB. I noticed that as a meditator, many of the verses in the Paul Reps translation of the scripture felt quite familiar.

Being a Sanskrit enthusiast and a panoptic optimist, I thought, "Why not write away to Kashmir and ask Swami Lakshmanjoo for his own translation?"

Some months later, it was with a sudden surprise that I received a letter informing me that Swamiji had been kind enough to fulfill my request.

His mother tongue, I learned, was Kashmiri. English, though, was then and remains the lingua franca. So to render the scripture's verses into the English of the Indian subcontinent's former colonial overlords, Swamiji enlisted the help of one of his trusted devotees, Pandit Dina Nath Mujoo, who was a beloved leader in the field of women's education. He offered his English and Sanskrit competencies, often meeting with Swamiji weekly to infuse the saint's fount of experiential and scriptural knowledge into their collaborative efforts to impart the meaning of that scripture.

Thus, a word is in order here to describe Swamiji's relationship with religious texts in general, as he explains in the Manual for Self Realization: 112 Meditations of the Vijñāna Bhairava Tantra, edited by John Hughes. This remarkable publication blends translation with Lakshmanjoo's disclosure of some of his tradition's oral teachings.

On pages 24–25, Swamiji comments on two kinds of relationships one can enjoy with a text.

The first type is textually oriented, with the text as the object of knowledge. One takes the "support" of the book and explains it.

Using the example of an important text in Kashmir Shaivism, the Tantrāloka, Swamiji explains below, a more-nontextual relationship to meaning:

Lakshmanjoo

I know the Tantrāloka. For the time being, I know the Tantrāloka [but] I have no books. I don't remember any śloka (verse) in my mind. In my mind, I don't remember any śloka, but whenever somebody asks me [about] some śloka, bas [the explanation] comes out. Where was that śloka residing in my brain? Where? In the nirvakalpa [free-from-thought] state. That is pramiti bhava [the state where subjective consciousness prevails without the agitation of objectivity. The state of pramiti is without any object at all].

The English expressions of the Vijñāna Bhairava (VBT) herein are a blend of (a) Pandit Mujooji's more textually oriented attention to bringing the verses over from Sanskrit into English and (b) the more subjective, self-referral expressions of Swamiji's enlightened consciousness.

Their intent was pedagogical: an expression of their deep and overflowing enthusiasm for sharing their knowledge.

In the realm of Divine Awareness, the scripture is Divinity's silent conversation with Itself: Knower, Knowing, and Known as one.

In our everyday world, the scripture is a book about Divine Consciousness.

As Swamiji explains, though, Divine Awareness is not an object to be known.

It is not about "about."

Divine Awareness is the Knower, pure awareness in its shoreless, self-referral state of knowing itself by means of itself.

Although Swamiji was kind enough to have created and shared these expressions with me and wanted to share them with others, the scripture, according to Swamiji, is for masters.

Swamiji: Actually, these processes are meant for masters. They are not meant for students. This is a book for masters.

John: Training guide.

Swamiji: Training guide, yes. How to teach people, in which way. (Manual for Self Realization, p. 9)

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

I do not presume to be a master, nor do I teach in this tradition.

Swamiji has, though, left behind some who have studied with him in person for years and who have diligently recorded many of his commentaries and teachings. These include John and Denise Hughes as well as George Barselaar. Betinna Bäumer also studied with Lakshmanjoo and teaches as well.

In addition, John Hughes listed the following scholars and visitors who visited Lakshmanjoo's ashram: Lilian Silburn and her colleague André Padoux, both scholars of Tantrism in Paris; Alexis Sanderson, a renowned professor at Oxford; and Mark S. G. Dyczkowski, then a young scholar of Shaivism associated with Sampurnananda Sanskrit University, Benaras. Some others are Professor Harvey P. Alper, Professor J. G. Arapura, K. Shivaraman, and the late Gerald J. Larson (one of my former Sanskrit teachers at UCSB).

From Benares came Pandit Rameshwar Jha and Thakur Jaidev Singh, both seeking a more profound understanding of Shaiva doctrine and practice. Pandit Rameshwar Jha composed the famous Gurustuti, a compendium of verses in Sanskrit on the greatness of Swami Lakshmanjoo and his masters.

The list above is, though, a view of Swami's visitors as seen through something of a Western lens, for many of Swamiji's local devotees, saints, and scholars, such as Pandit Mujoo and others, were of Swamiji's own culture, so the entire list of Swamiji's visitors is much larger.

Among his local friends and neighbors in Kashmir, Swamiji taught once per week, usually in the full eloquence of his mother tongue, Kashmiri, which is somewhat close to Sanskrit. Or in Hindi. So, many within Lakshmanjoo's own cultural sphere are steeped in the knowledge of this last master in his lineage.

L to R: Maharishi Mahesh, Swami Lakshmanjoo, Denise Hughes

The photo above is another from the late sixties when, as already mentioned, accompanied by graduates from his Teacher Training courses in Rishikesh, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi began traveling to Kashmir. It was then that Maharishi met with Swami Lakshmanjoo, who shared with him the Shiva Sutras and each of the 112 ways of the Vijñāna Bhairava.

Swamiji, Anandamayi Ma, and other great saints would always advise Maharishi's students to continue with the meditation Maharishi had taught them. On some occasions, Anandamayi Ma would send students to Maharishiji for instruction.

It should be noted that Maharishiji always taught on behalf of his own remarkable teacher, His Divinity Brahmananda Saraswati of Jyotir Math.

It was from him that Maharishiji passed on the self-referral dynamics of consciousness as one awakens from a state of duality to a state unity of Knower, Knowing, and Known.

In guiding us into the effortlessness of researching within consciousness, Maharishiji also encouraged much scientific research on the effects of meditation and on the group dynamics of consciousness.

The results proved that groups of meditators can enliven a field effect that ripples outward and radiates peace through the environment. On the basis of these results, Maharishiji initiated many peace projects around the world.

Transcendental Meditation around the World

The Mother Divine Program in Asia

TM in Ukraine

TM in Palestine

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

By 1975, when I finally received Swamiji and Panditji's written teachings on Kashmir Shaivism, I had already been meditating one pointedly for some seven years and was overflowingly awed and thankful for the absolutely effortless unfoldings within my heart.

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi had shared that unfolding with so many that at the University of California, as with most university campuses in the US at that time, some 10 percent of the student body were meditating. My work–study job at UCSB, for which I had been trained over a few years, was to sit with students individually meditate with them, and field any questions and concerns about their meditations. Probably the world's best job.

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

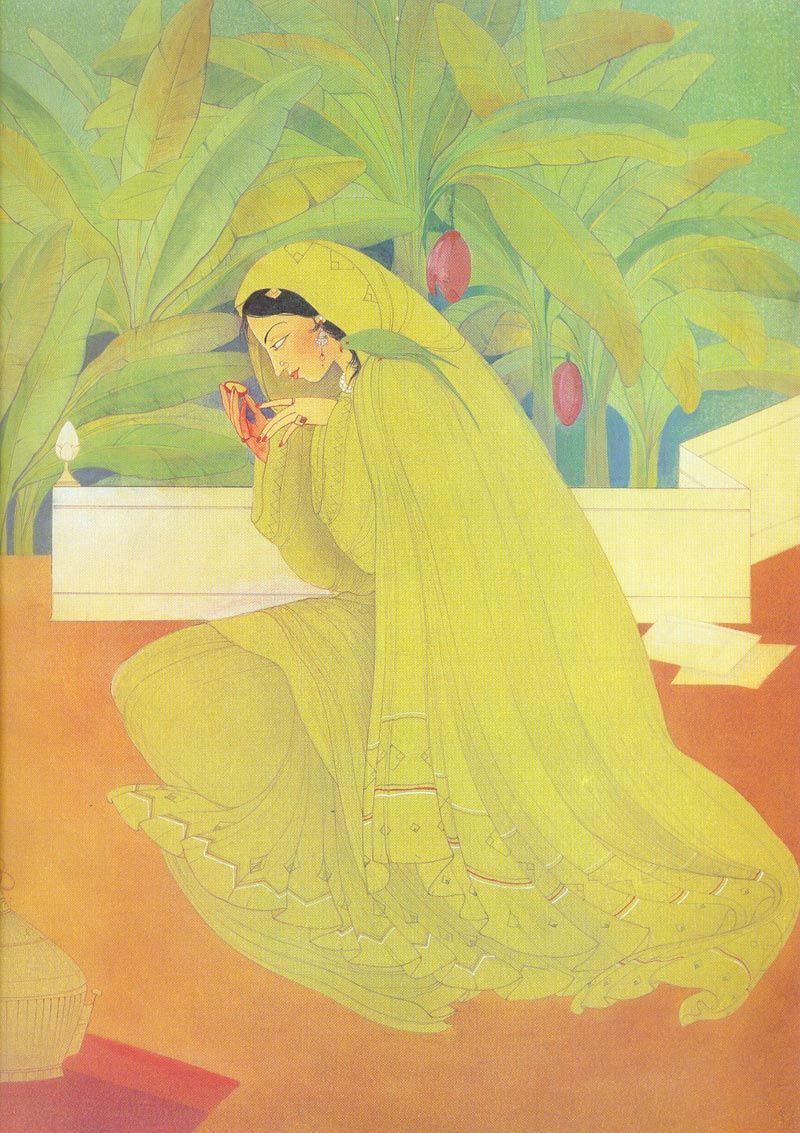

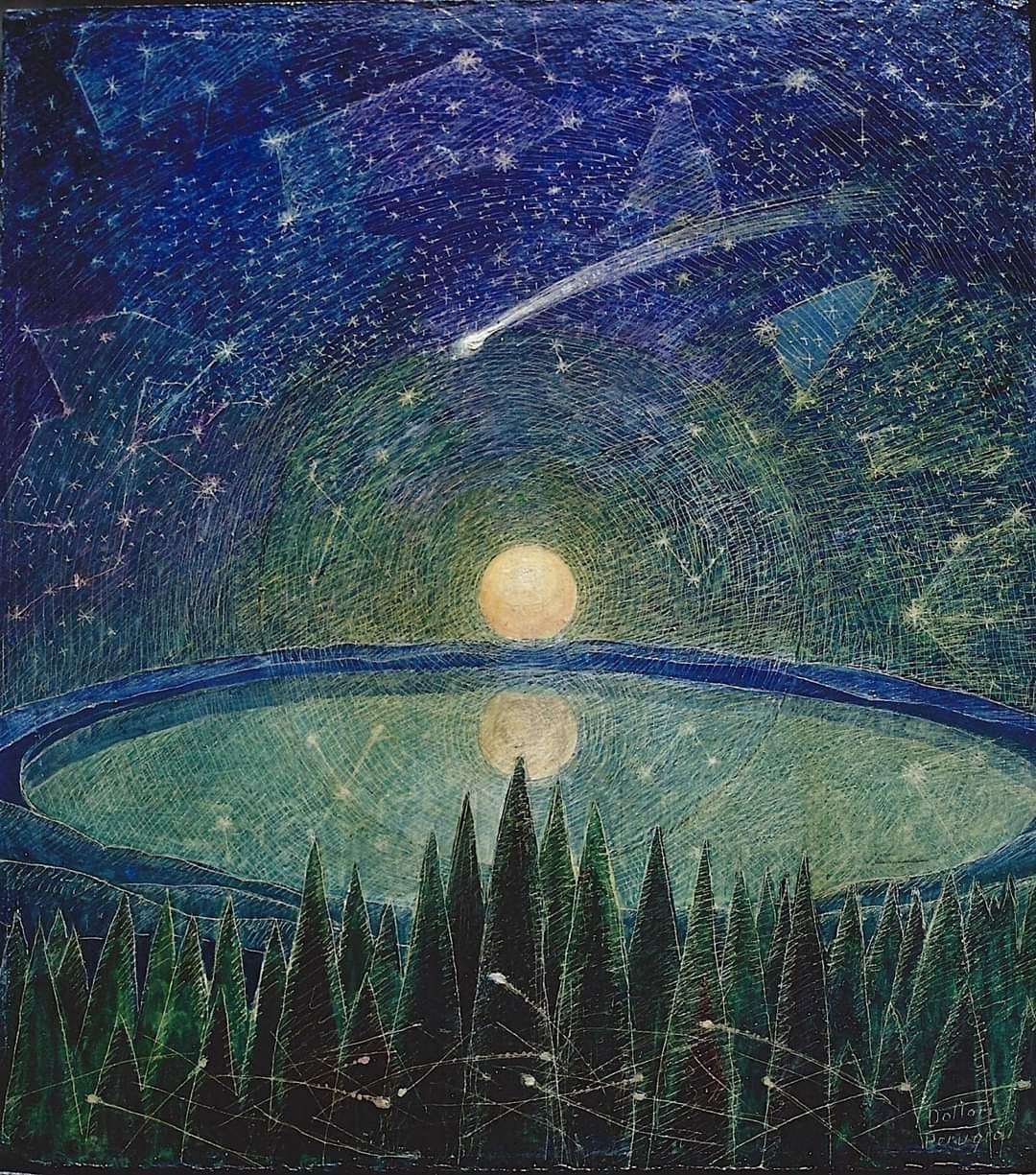

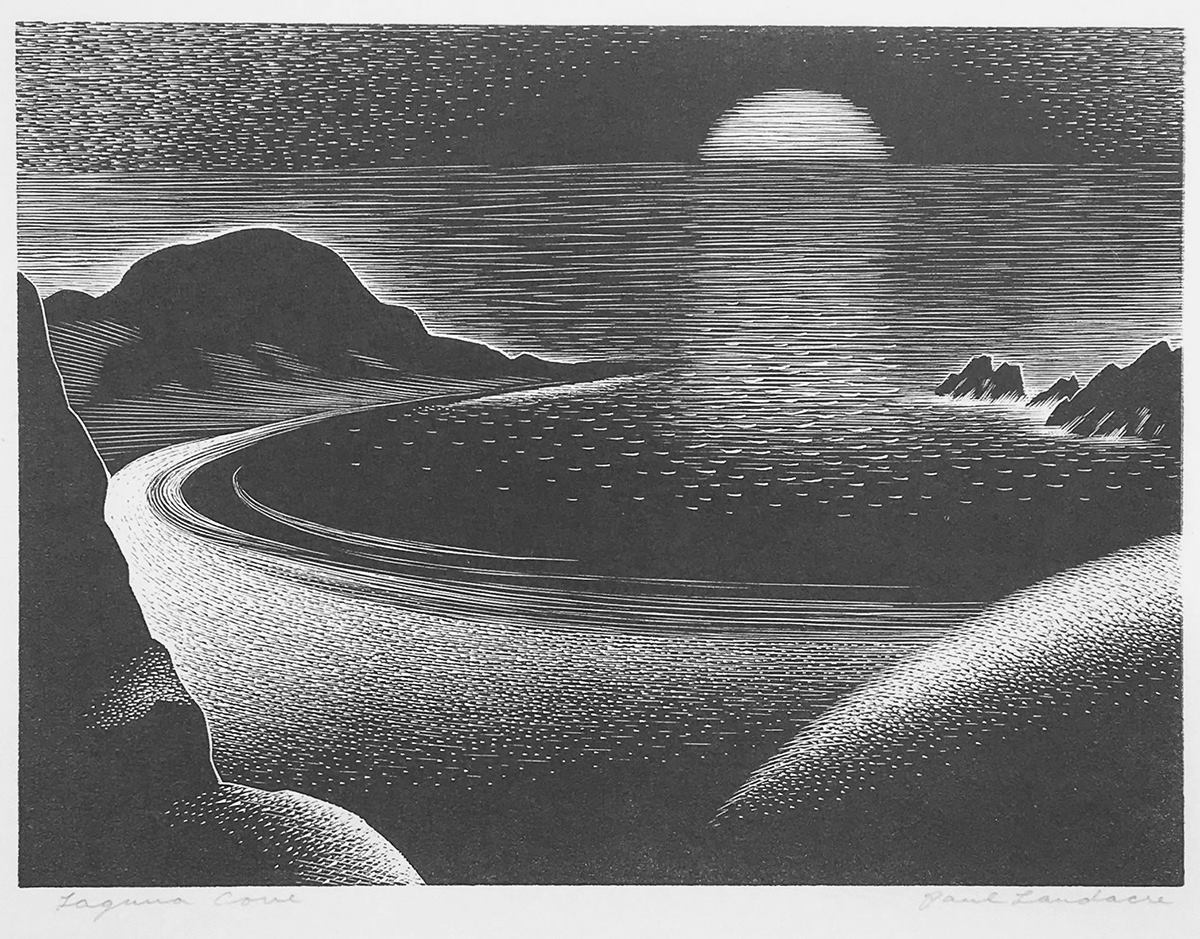

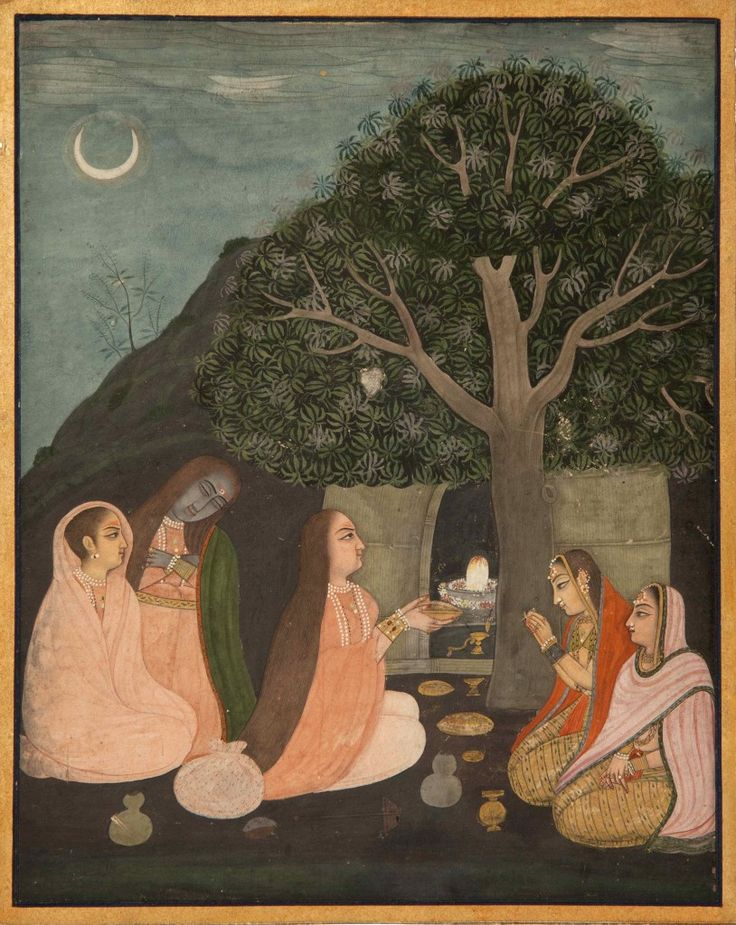

Like Alice situated within her own Wonderland, I have never believed a book is complete without illustrations. So, over the years (and still in process), I've devoted time to collecting apt images—at least one per verse. Some images are Western, some are Indian miniatures.

I would like to thank Laura Makabresku for offering her transporting images to help illustrate this labor of love.

This project will most probably continue to be in progress for some time further.

Jim Powell

2023