meditation 49

Whersoever the mind

rests in peace,

let it remain.

Supreme peace

prevails.

Notes:

Swami Lakshmanjoo insists on the universality of the scripture's teachings. After all, many traditions teach breath-based meditation. In some souls, suspension of breath even happens spontaneously.

This verse is one of the most generously universal. Wheresoever is an all-encompassing word.

The word includes landscapes far afield from those of medieval Kashmir.

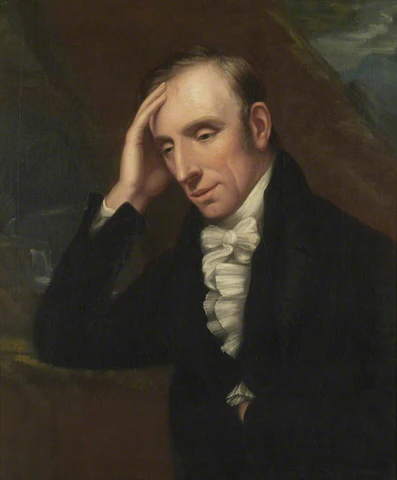

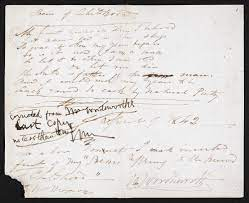

The where that Lake Poet William Wordsworth put on the map was a luminous and tranquil transcendental realm, a kind of terra incognita, which, once spread out before his readers, they recognized as their own souls.

As the literary critics Harold Bloom and Lionel Trilling wrote, "Before Wordsworth, [English] poetry had a subject. After Wordsworth, its prevalent subject was the poet's own subjectivity , , , and so a new poetry was born."

And although William Wordsworth was certainly not aware of the Vijñāna Bhairava, some of the scripture's verses do speak to the very core of his spiritual and aesthetic heart: his responses to the sounds of streams and waterfalls, to all-enveloping darkness, to the alluring spaciousness of a clear blue sky, to the devout stilling of human breath.

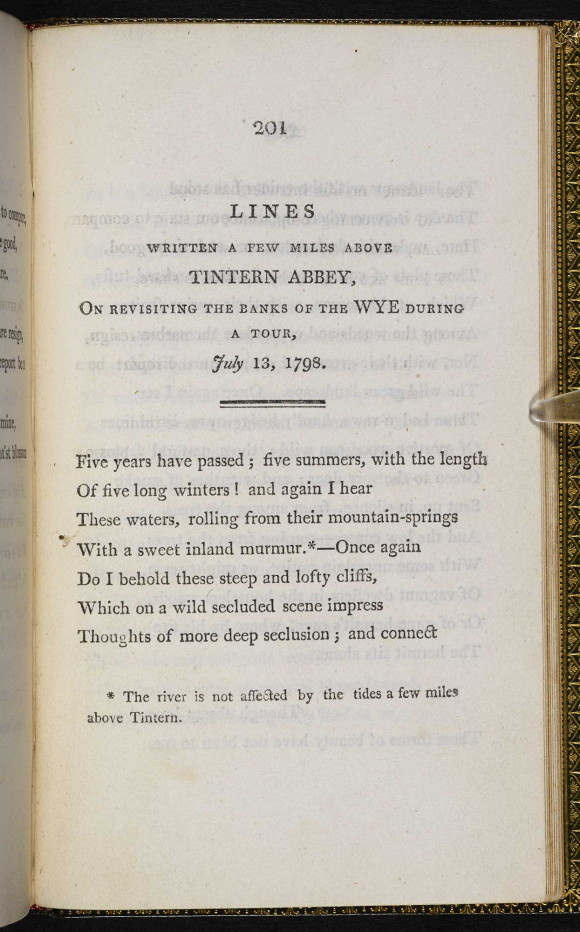

It was Wordsworth who penned a poem that – for its contemplative tone and content – was to become famous as far afield as India.

The poem celebrates what happens when Wordsworth's awareness dwells upon his recollections of a locale, a wheresoever where he became absorbed in profound peace.

Many centuries ago, it was Kashmir's great yogi and philosopher Abhinavagupta who cleared the path for Wordsworth's wander into Indian hearts and minds. He did so by stating that the underlying essence (rasa) of aesthetic experience is Shanta Rasa: the rasa of tranquility, the silent bed of awareness upon which the comic, the tragic, the heroic, the erotic, and all the other rasas play out their roles.

Artists and connoisseurs whose hearts remain afloat in the rasa of tranquil awareness are said to be of the same heart (sahṛdaya).

Although some Indian professors of English Literature once felt that Wordsworth must have been Hindu or was at least directly influenced by Hindu thought in his writings about immorality, there is little evidence to that effect.

Wordsworth did, however, in addition to rhapsodizing about immortality, define poetry in rather Abhinavagupta-esque terms: as "emotion recollected in tranquility."

In India, Wordsworth's poem "Lines Written a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey" is thought to poetically embody emotion as quietly as does a nun breathless with adoration.

Five years have passed; five summers, with the length

Of five long winters! and again I hear

These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs

With a soft inland murmur. –Once again

Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs,

That on a wild secluded scene impress

Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect

The landscape with the quiet of the sky.

The day is come when I again repose

Here, under this dark sycamore, and view

These plots of cottage-ground, these orchard-tufts,

Which at this season, with their unripe fruits,

Are clad in one green hue, and lost themselves

'Mid groves and copses. Once again I see

These hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines

Of sportive wood run wild: these pastoral farms,

Green to the very door; and wreaths of smoke

Sent up, in silence, from among the trees!

With some uncertain notice, as might seem

Of vagrant dwellers in the houseless woods,

Or of some Hermit's cave, where by his fire

The Hermit sits alone.

These beauteous forms,

Through a long absence, have not been to me

As is a landscape to a blind man's eye:

But oft, in lonely rooms, and 'mid the din

Of towns and cities, I have owed to them,

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart;

And passing even into my purer mind

With tranquil restoration: – feelings too

Of unremembered pleasure: such, perhaps,

As have no slight or trivial influence

On that best portion of a good man's life,

His little, nameless, unremembered, acts

Of kindness and of love. Nor less, I trust,

To them I may have owed another gift,

Of aspect more sublime; that blessed mood,

In which the burthen of the mystery,

In which the heavy and the weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world,

Is lightened: –that serene and blessed mood,

In which the affections gently lead us on, –

Until, the breath of this corporeal frame

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul:

While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things. . . .

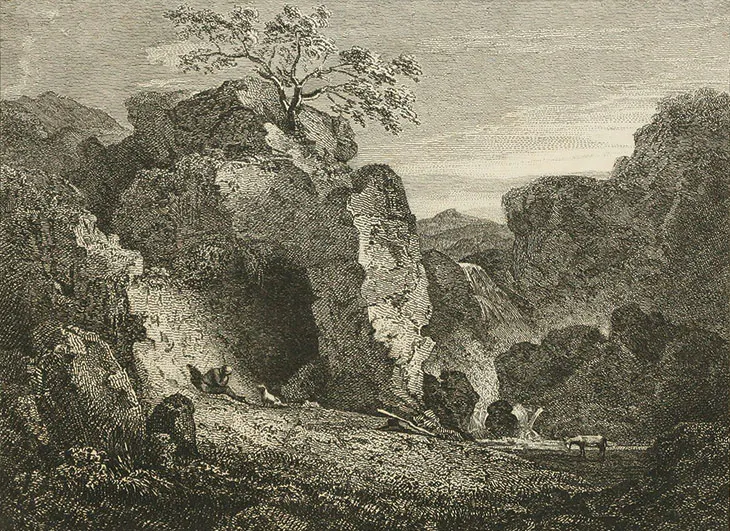

As for those hermits hidden away in the woods of Great Britain, estate landscapes strewn with boulders, dense clumps of uprooted trees, and moldy, crumbling cottages were not dismissed as wastelands devoid of any sense of compositional logic.

In their storm-ravaged and dark recesses, they gave testament to a sense of the Romantic Sublime, or to an introspective form of melancholy — lending a certain Byronic allure.

These unfrequented haunts, grottoes, and sun-deprived glades offered not only darkness but also niches for a sagacious sense of solitude.

Many estate owners, however, built hermitages only to discover that they, themselves, were neither particularly contemplative nor sagacious.

The obvious answer was to lure an Ornamental Hermit to haunt and hallow such a hollow. It is easy for readers to see how, in myriad English and Indian hearts, Wordsworth became the hermit of choice.