The Life and Teachings of Swami Lakshmanjoo

⛛▼⛛

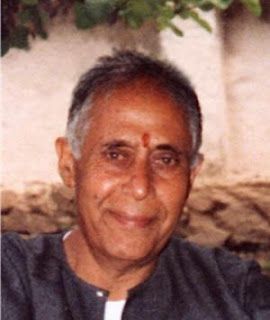

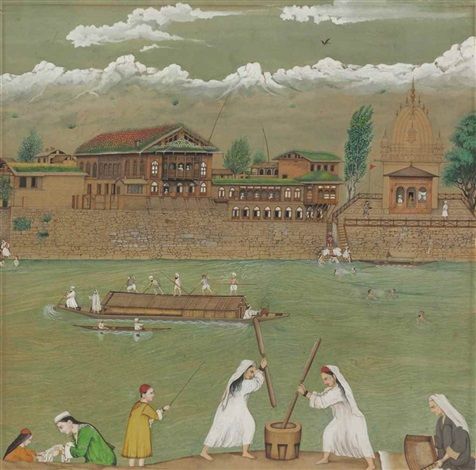

Born in an affluent middle-class family in 1907, the young Lakshman had every chance of becoming a successful gentleman appropriate to his times. His father, Shri Naryanjoo, was a thriving businessman and enjoyed a respectable position in society. At that time a great savant and saint, Shri Swami Ramaji, happened to be living in Kashmir. Swami Ramaji, besides being a profound scholar of various systems of Indian philosophy, had dived deep into the mysteries of Shaivism and the Tantras. He had not merely studied the Tantras but had gone into their mysteries experientially. How far he had gone on this path is beyond our ken, but supernatural powers often exhibited by him and the personal experiences narrated by his disciples compel one to take him to have been a man of realization.

During the latter part of his life, Swami Ramaji happened to take his abode in one of the houses owned by Shri Narayanjoo. Thus Narayanjoo had the good fortune of coming in close contact with this great saint, whom he served with heart and soul. When the baby Lakshman was born, the saint, on hearing the news of his birth, was overjoyed and declared that a great soul had incarnated, whom he would call his younger brother, Lakshman, he being the "older brother" Rama.

The prophecy began early to appear true. Even at the age of five, the boy Lakshman used to go into trance. The father gave him the usual type of education prevalent at that time. The boy’s progress in studies was normal, but his behavior was somewhat different from that of the other boys at school. He was not given much to play or fun as were the others but preferred to sit alone, in a meditative mood.

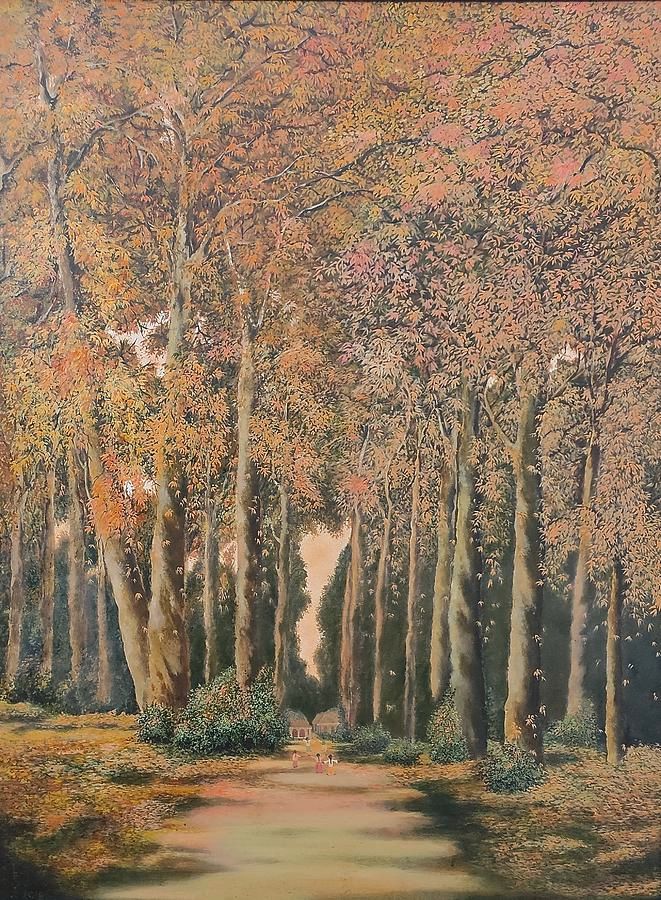

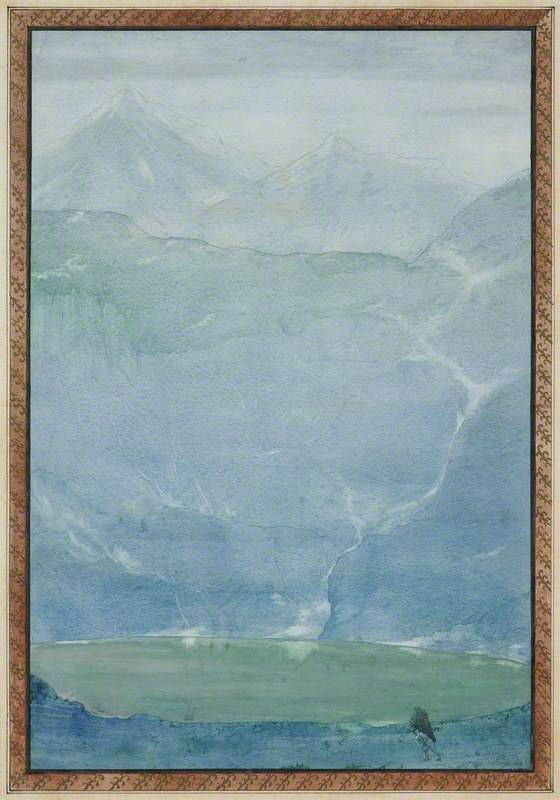

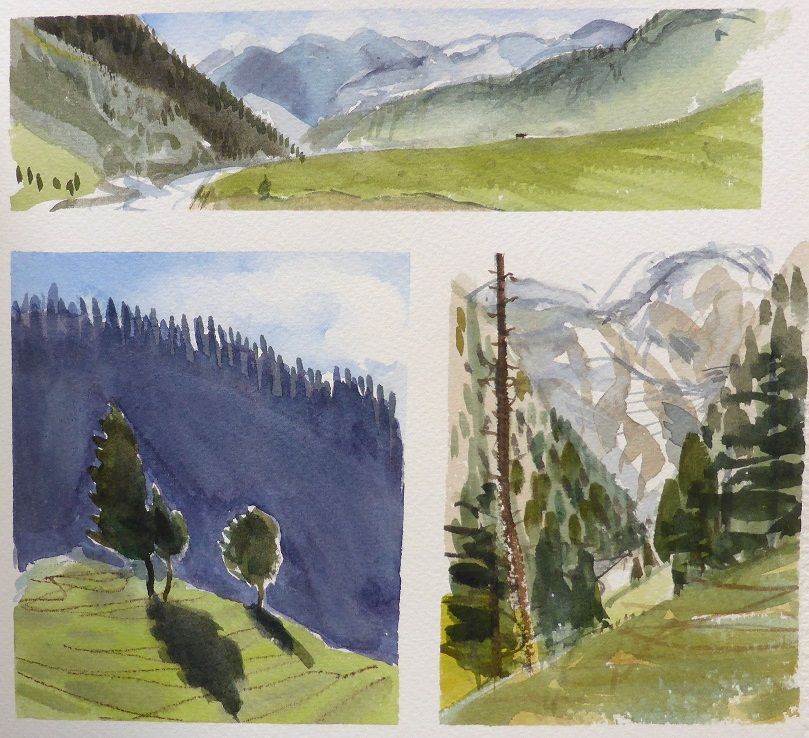

When he was about twenty years of age, he left his home one day, leaving behind a message written on a slip of paper informing his parents that he was going away “in search of the Highest.” The impetuous youth was searched out and found meditating in a forest hermitage, a hallowed place away from the common haunts of man, about sixty kilometers from his hometown, Shrinagar. His father persuaded him to return to his home, however, promising to build a hermitage for him on Ishbari mountain, a place renowned as the abode of ancient Shaiva saints, at a distance of only twelve kilometers from Shrinagar. The building came up, and the young Lakshman moved there to lead a life of his own, devoted to study and spiritual experience.

When Swami Lakshmanjoo was born, Swami Ramaji was fairly old. He passed away when the young Lakshman was only eight years of age. Before his departure from this world, however, Swami Ramaji entrusted the work of the spiritual guidance of the boy to his chief disciple, Swami Mahtab Kak. In due course, young Lakshman expressed his eagerness to undergo spiritual discipline, and Swami Mahtab Kak was only too willing to instruct him.

Swami Mahtab Kak was a man of spiritual attainment but was not as scholarly as had been his great preceptor, Swami Ramaji. So while he guided his young disciple in spiritual practices, he was not particular for any deep study of texts. The young Lakshman’s thirst for knowledge, however, was great. He wanted to fathom deeper and learn for himself what the ancient teachers had taught. Fortunately for him, an illustrious scholar of Shaivism, Shri Maheshwar Nath Razden, was living in those days. So, Lakshman approached him and began his study of Shaiva texts. Devoting the whole of his energy night and day to his studies, he soon attained mastery over almost all the texts, which, aided by spiritual experience, became illumined for him. Swami Lakshmanjoo, then, possesses not only a full intellectual grasp of the ancient texts of Shaiva philosophy but carries with it the practical knowledge of his personal experiences. This, no doubt, makes him, at present, the greatest living Shaiva teacher in Kashmir and perhaps one of the greatest teachers in India, too.

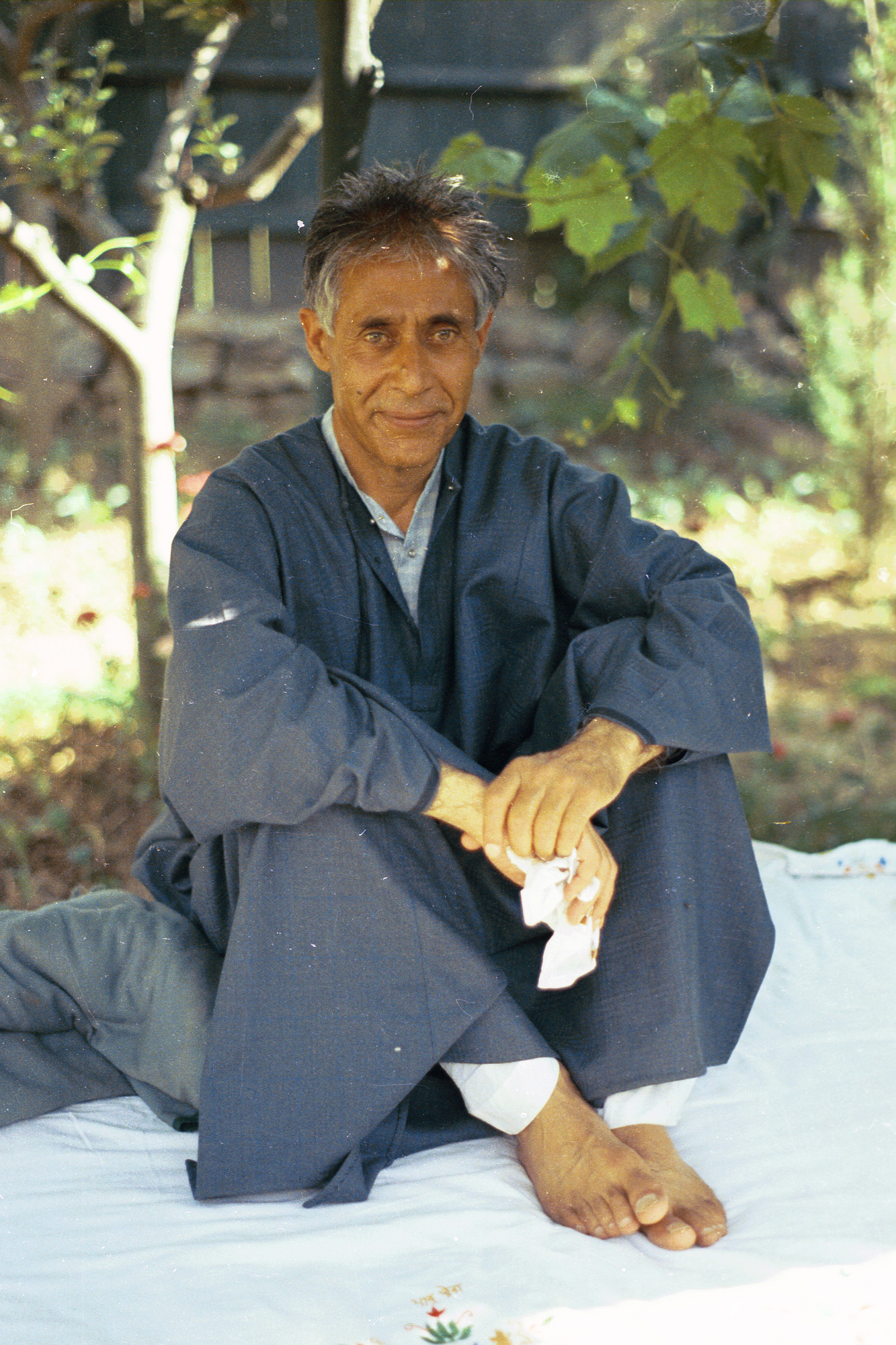

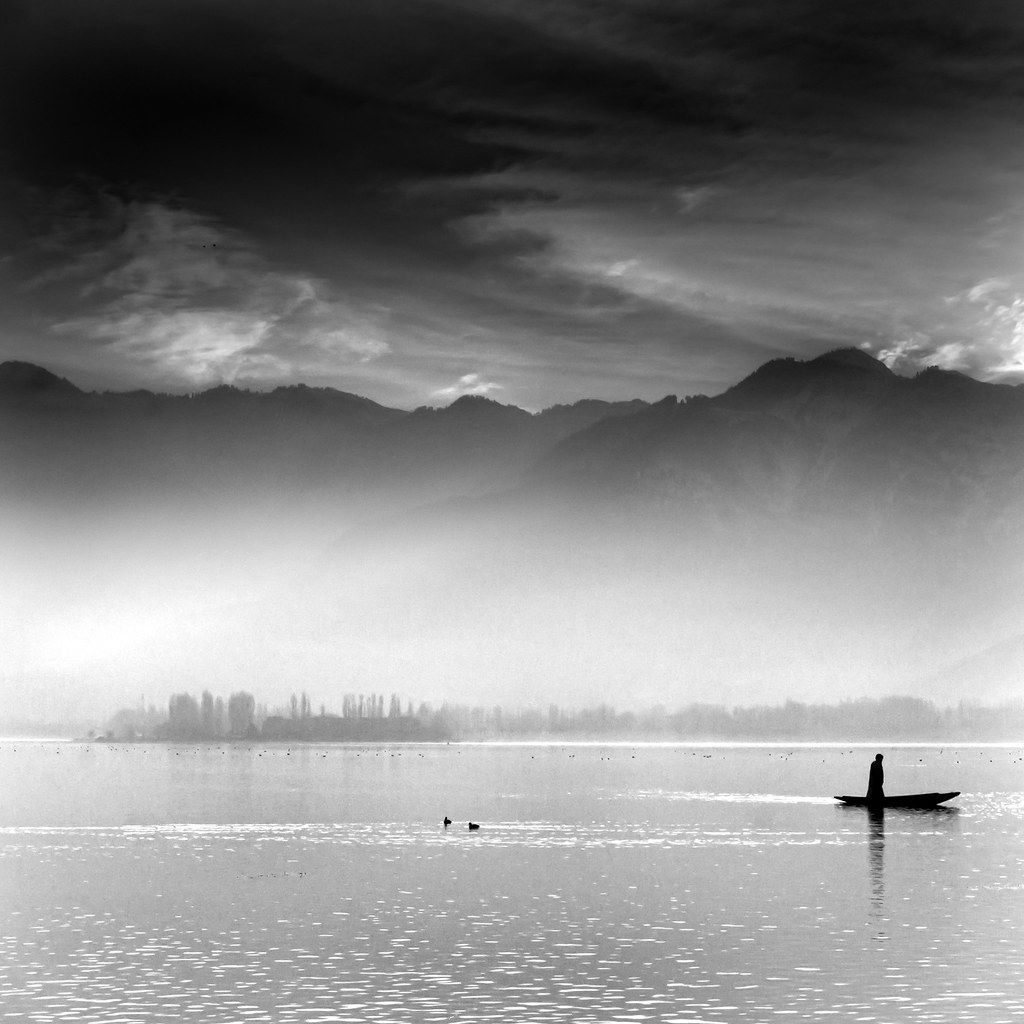

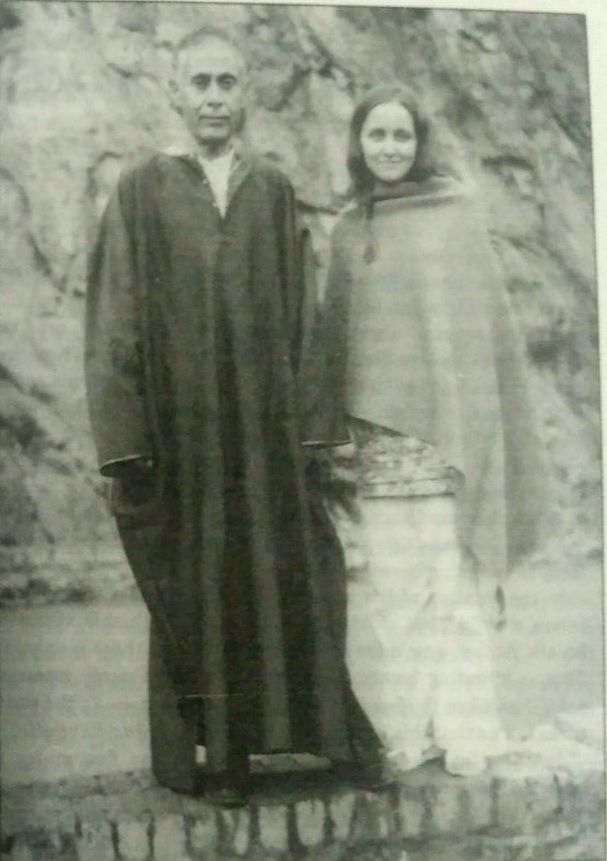

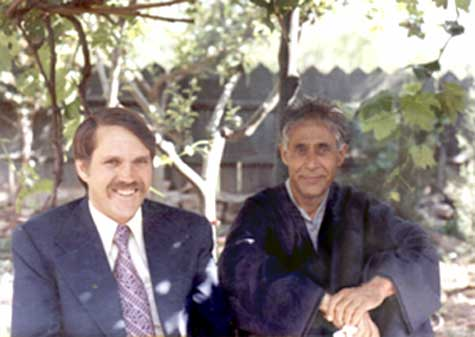

He lives at his little home at Gupta Ganga, Shrinagar, outwardly like a country gentleman of Kashmir, looking after his little garden, caring for flowers and lawns and one or two cows, which he keeps. He is usually bareheaded, except in frigid weather, and wears a long gown-like dress, not much different from the dress worn by the older generation of Kashmiris. He puts on no caste marks nor wears any rosaries or similar symbols to show outwardly that he is a saint or a religious teacher. For all intents and purposes, he looks like an ordinary householder.

His personal life, however, is austere. He has never touched meat, liquor, or tobacco and is a celibate. He spends most of his time in study and meditation. Generally, he lives a life of his own for six days of the week, when few people can meet him, except by appointment, but on Sundays, he keeps an open house. There is generally a gathering of about one or two hundred men and women, both young and old, on this day. From morning till dusk, one can see him sitting, with his smiling face and affection beaming from his beautiful eyes, listening and talking to individuals and groups. It is on this day, too, that he holds a regular class, usually from noon until half past two in the afternoon, in which he teaches Shaiva texts.

He enjoys his afternoon tea on this day, with all those who are present. It is often during these informal meetings that, if the right question is posed, many doubts and uncertainties are cleared. He is always ready to give.

Though Swamiji has had very little formal education in modern languages and prefers to teach in Kashmiri, he sometimes, as necessity arises, teaches in English also, for the benefit of European and American scholars and aspirants who come to him from abroad to understand the traditional and occult meaning of the Tantras or for spiritual guidance. Such classes are usually held on Saturdays, in the afternoon. The teaching thus given carries, of course, no obligation with it.

Thanks to Providence, Swamiji’s personal needs are met out of the patrimony inherited by him. So, he is not dependent on his disciples for his maintenance, nor is he anxious to build an ashram after his name, for which he should need to collect donations. This fact gives him a unique position of freedom.

Swamiji’s teachings are not very much different from the main teachings of the Monistic School of Kashmir Shaivism. These teach that Shiva—the ultimate Reality, the First Cause—is not to him only transcendental unmanifest Reality, but also the Immanent and in manifestation, too. He says all that is, exists because it primarily resides in Shiva. We are because Shiva is—the only difference being that while Shiva is a state of absolute Freedom, Bliss, and Light, we are in a state of ignorance, being wrapped by the threefold impurities of (a) feeling a sense of individual or separative consciousness, (b) feeling the objective universe is other than Shiva, and (c) feeling an attachment to the fruits of our individual actions. Swamiji teaches that Shiva, being omnipresent, can be realized in any and every walk of life. Hence, so-called renunciation of the world is not needed, nor are any rites required to invoke Him. Vasu Gupta has said in the Spanda Karika:

tasmatsabdartha chintasu nas

avastha nay a Shivah

Hence, there is no state of consciousness in the contemplation of word or object (observer/observed, subject/object) that is not Shiva.

To the writer, Swamiji is living in that state of consciousness. Whenever he explains some practice—and there are many practices in the Shaiva system—his whole emphasis is on awareness and one-pointed attention. He says that while eating, walking, talking, or doing any other action, one's whole attention should be given to that.

He adds that one should not, for instance, while walking, be aware of every step only, but should also observe the interval between two steps.

If one is taking tea, the interval is between two sips.

If one is listening to music, it is between two notes.

It is within these intervals, when observed in silence, that enlightenment dawns.

He maintains that for final enlightenment, only awareness is required.

One day, we had quite a large gathering by a mountainside outside Shrinagar, where arrangements for a night’s board and lodging had been made by a disciple of Swamiji. It happened that the weather turned rough. Swamiji, as would have any intelligent man of the world, went around seeing that everything was alright. Although almost everything appeared upset, Swamiji went about calmly and with an unruffled countenance. The writer happened to watch him rather closely, and when he took a seat for a while and no one else was within hearing distance, I managed a word with him. I referred to a verse in the Kakhyastotra, meaning by implication that Swamiji was enjoying, in the state of consciousness, the whole scene. Swamiji smiled with a nod in return, thus acknowledging what was said as true. The verse reads as follows:

Sarvah shakticetas darsanadyah

Sve sve vedye yaugapadyen visyak

Kshiptva madhye hatakastambha bhuta

Stisthanvishadhare aiko-bhasi.

Letting all the sense, sight, and so on,

Feast simultaneously on their respective objects,

Stand in the center,

Shining like a pillar of gold supporting the entire universe.

Whatever practices Swamiji might have followed in his early years, especially for rousing Kundalini, or maybe doing now, Swamiji stresses the point that God consciousness can be revealed while living an ordinary life in the world. The only requirement is that we must let our individuality go for universality to come. In the absence of this, no practice is of any avail.

Yet, it is not so easy as it may appear at first glance to be with Swamiji and make demands for his guidance. He maintains that before setting foot on the path of discipleship, the aspirant must have purified his conduct, thoughts, and feelings. He must be free from greed, anger, hatred, and lust. These are preliminary requirements. Only then can one aspire to really enter the Path, where one will have to dissolve his very ego, the limited “I,” for the universal “I” to manifest: to let his I-Consciousness merge in the universal consciousness. One has first to withdraw inward for realization of God consciousness and then come out and see all the manifestation as the play of that very consciousness.

Though a Shaiva savant, Swamiji has an open mind for other systems of thought whose aim is the spiritual unfoldment of the individual. Hence, one can find scholars and aspirants of various schools of thought coming to meet him, discussing spiritual problems with him, and listening to his talks. And he meets all with affection.

It is said that a country without saints is like a land without trees, under the shade of which travelers, tormented by the heat of the midday sun, could rest. Kashmir, today, is fortunate in having a majestic tree with outspread branches, in the person of Swamiji, offering shelter to many a weary traveler.

~ Dina Nath Muju, 1974

Note: After Dina Nath's passing, in the 1990s, his family compiled a book of his writings, dating the essay above to 1983. It was, however, written nine years earlier, in 1974, and then sent to me in Santa Barbara.

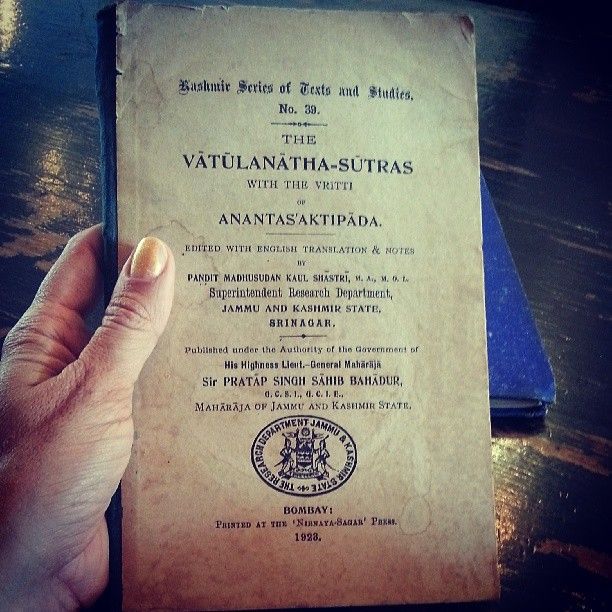

You may discover some of Dina Nath's other writings by clicking on the image below. This is one of the reading materials the kind pandit was good enough to share with me. These also included some volumes in the Kashmir Series of texts.

The short story is accompanied by a photo of Dina Nath's wife, who was blind.

Dina Nath devoted much of his life to educating women. Being a supporter and admirer of J. Krishnamurti, Dina Nath was also non-dogmatic in his thinking, looked to get to the essence of things, and was kind and intelligent. One can feel the man's gentleness and genius in his laconic renderings of the scripture.

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

The following biography appears on the Swami Lakshmanjoo Facebook page.

Lakshmanjoo Raina was born at Namchibal, in Śrinagar (Kashmir) on May 9, 1907. He was the fifth child in a household of four boys and five girls. His father was Narayandas ("Nav Narayan") Raina and his mother was Arnyamali Raina. At the age of five, he was introduced to the path of spirituality by his elder brother Maheshvaranath.

Up to the age of eight, his spiritual progress in the lineage of Kaśmīri Śaivam (note 1) was monitored by his family priest, Pandit Swami Rama Joo, from the tradition of the Tantric Monism of Kashmir (Trika System).

Just before entering mahāsamādhi (note 2), Swami Rama Joo entrusted the seven-year-old Lakshmanjoo to his disciple Swami Mahtab Kak.

At sixteen, Lakshmanjoo was initiated by his Guru, Swami Mahtab Kak. At the age of nineteen, Lakshmanjoo experienced a clear taste of Self-realization. Shortly afterwards he left home, as he wrote, "in search of the Supreme" and moved to the famous forest ashram of Sadhamalyun (Sadhuganga) in Handawara, Kashmir.

Persuaded by his father to return to Śrinagar, he continued to study and engaged Pandit Rajanaka Maheśvara to teach him Śaiva Śastra at home. He also studied Sanskrit grammar and the other schools of Indian philosophy at full length. He edited the Bhagavadgītā with its Sanskrit commentary by Abhinavagupta and wrote important footnotes to it. This was published when he was about twenty-five years old. In 1934-35, he moved to an isolated place above the village of Gupta Gaṅgā near Nishat suburb of Śrinagar where his parents built him a house. This was a place where Abhinavagupta had lived nine centuries before.

In 1962 he moved down the hill to a bungalow built by his parents, closer to Dal Lake, a short distance from the Mogul garden of Nishat Bagh. Adjacent to Lakshmanjoo’s location, Śri Jia Lal Sopori of Śrinagar built a house for his daughter Sharika Devi, who, after taking a vow to lead a celibate life, took Brahmacāri Lakshmanjoo as her preceptor.

Deviji learned Agama Śastra from him and practiced Śaiva-yoga under his guidance. Overwhelmed by her experience, she lost her mental balance for a few years when she had to be moved to her parent's house. Later, Lakshmanjoo who went to see her, gave her a grape to eat, and then she started improving and then regained her normal condition. Lakshmanjoo also initiated Prabha Ji, the younger sister of Sharika Devi.

Sunday classes started at the āśrama, which attracted an increasing number of devotees.

Around the age of 30, he traveled in India, spending time on a Mumbai beach and a short time with Mahatma Gandhi at Sevagram and then with Śri Aurobindo at Pondicherry. From there he went to Tiruvannamalai to meet Ramaṇa Maharṣi. There he spent some weeks and later commented; "I felt those golden days were indeed divine."

Upon returning to his āśrama he wrote a Hindi translation of the Sāmbapañcāśikā, adding important hints as footnotes to it. This was published in 1943. He went into strict seclusion for several months. During that period, he concentrated on the Kramastotra from the Tantraloka. He made an exposition of the twelve forms of Śaiva Yoga in Hindi preceded by the original Sanskrit text in a small book that was published in 1958.

Lakshmanjoo propagated the Śaiva teachings and people started seeking him, both from his own country and from abroad. Around 1957 Lakshmanjoo disposed of his estate and started to live in a small house newly constructed near Gupta Ganga Temple in Ishaber village.

“Ishwara Āśrama” was the name given to the āśrama and the disciples began to call Swamijī Īśvara Svarūpa (note 3), which later became the headquarters of Īśvara Āśrama Trust. Little was known about the Swami for almost three decades (1930-1960), as it was his habit to spend the winter months in silence and seclusion. Still, in the summer he had occasional visits from both scholars and saints. The Indian Spiritual Master Meher Baba visited his ashram in 1944. In 1948 Lilian Silburn from the National Centre for Scientific Research, Paris, visited the Swami. She would return regularly for the next ten years, during which time she studied the major texts of Kashmir Śaiva philosophy, all of which were published in French. It was through Silburn that André Padoux, another prolific scholar of Kashmir Śaivism came to meet the Swami. Paul Reps, the American artist, author and poet came to the Ashram in 1957 and with Swami Lakshmanjoo he studied the ancient text of Vijñāna Bhairava Tantra and later published the 112 practices of transcending in the fourth chapter of his book Zen Flesh, Zen Bones. This teaching also influenced Osho and formed the basis of The Book of Secrets.

It was a few years later, in 1965, after attending a Sanskrit conference in Varanasi, chaired by the renowned Sanskrit Tantra scholar Gopinath Kaviraj, that the word quickly spread that the tradition of Kashmir Śaivism was alive and well, and fully embodied in the person of Swami Lakshmanjoo.

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi visited the Swami each summer from 1966 to 1969. The two saints formed a lasting relationship.

Baba Muktananda, of Siddha Yoga, also visited on two occasions.

⛛▼⛛

Until his death, on 27th September, 1991, Swami Lakshmanjoo freely taught, giving weekly lectures on the mystical and philosophical texts of Kashmir Śaivism. Many of these lectures were audio recorded by John Hughes and later published. Lakshmanjoo's interpretation of Kashmir Shavism attracted the attention of both Indian of Western Indologists. The Swami has correspondence with Professor Giuseppe Tucci of the University of Rome La Sapienza, and his regular visitors included scholars, such as Jaideva Singh, Professor Nilkanth Gurtoo, Acharya Rameshwar Jha, Jankinath Kaul "Kamal", Raniero Gnoli, Alexis Sanderson and Mark Dyczkowski.

In 1991 Swami Lakshmanjoo traveled to the United States and established the Universal Śaiva Fellowship where he designated John Hughes and his wife Denise to continue publishing his teachings of Kashmir Śaivism. In India, the teachings of Lakshmanjoo are carried on by Ishwar Ashram Trust, an organization founded shortly after his death. According to the late Pandit Shri Jankinath Kaul, “Though Swamiji was a master of occult powers, he never made a display of those powers. Swamiji was against their being used as he was convinced that the use of occult powers was an impediment on the spiritual path. He was the master of self-control and care. However, he appeared to have made use of his divine power sparingly and with great caution. Not only his close disciples but also un-acquainted people of different beliefs, from far and near, some of whom had not even met the Swami in person, were convinced of his powers which he might have used un-assumingly for their upliftment. Certain contemporary saints of the country have said that Swami Lakshmana Joo had been strictly guarding his earned treasure of powers and, if at all, he used those scarcely. His awe-inspiring sight and proverbial sympathy drew people from all walks of life near him with their problems to which he was often sharp in making decisions. It was also observed that he gave a healing touch to those who needed it. Common people believed him to be a redeemer from evil. Some persons of pure heart felt a current of mysterious joy running through their body while receiving his touch on bowing at his lotus feet.

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

To enable his commentary on this scripture to endure down through the ages, Swami Lakshmanjoo left it in two other forms:

(i) a series of videos gracing each verse, which over a few years, John Hughes of the Lakshmanjoo Academy recorded, and

(ii) Swami Lakshmanjoo's textual embodiment of the tapes, The Manual for Self-Realization: 112 Meditations of the Vijñāna Bhairava Tantra (edited by John Hughes).

Both are treasures! In each, Swamiji comments on the scripture while responding to questions from his students. Swamiji emphasizes that the video version transmits his teaching with a higher level of fidelity.

Footnotes

1. Kashmir Śaivism or more accurately Trika Śaivism refers to a nondualist tradition of Śaiva-Śakta Tantra which originated sometime after 850 CE. Though this tradition was very influential in Kashmir and is thus often called Kashmir Śaivism, it was a pan-Indian movement termed Trika by its great exegete Abhinavagupta, which also flourished in Oḍiśā and Mahārāṣṭra. Defining features of the Trika tradition is its idealistic and monistic pratyabhijñā ("recognition") philosophical system, propounded by Utpaladeva (c. 925–975 CE) and Abhinavagupta (c. 975–1025 CE), and the centrality of the three goddesses Parā, Parāparā, and Aparā. While Trika draws from numerous Śaiva texts, such as the Śaiva Agamas and the Śaiva and Śakta Tantras, its major scriptural authorities are the Mālinīvijayottara Tantra, the Siddhayogeśvarīmata and the Anāmaka-tantra. Its main exegetical works are those of Abhinavagupta, such as the Tantrāloka, Mālinīślokavārttika, and Tantrasāra which are formally an exegesis of the Mālinīvijayottara Tantra, although they also drew heavily on the Kali-based Krama subcategory of the Kulamārga. Kashmir Śaivism claimed to supersede Śaiva Siddhanta, a dualistic tradition that scholars consider normative tantric Śaivism. The Śaiva Siddhanta goal of becoming an ontologically distinct Shiva (through Shiva's grace) was replaced by recognizing oneself as Shiva who, in Kashmir Śaivism's monism, is the entirety of the universe. (Wikipedia)

2. The great and final samādhi, is the act of consciously and intentionally leaving one's body at the moment of death. A realized and enlightened (jīvanmukta), yogi (male) or yoginī (female) who has attained the state of nirvikalpa samādhi, will, at an appropriate time, consciously exit from their body and attain Paramukti. This is known as mahāsamādhi. This is not the same as the physical death that occurs for an unenlightened person whose death comes when it may. In Hindu or Yogic traditions mahāsamādhi means that a realized master has consciously left their body; often while in a deep, conscious meditative state.

3. Īśvara: inner God; Svarūpa: essence; the true essence of God.

⛛▼⛛