meditation 1 : verse 24

ऊर्ध्वे प्राणो ह्यधो जीवो विसर्गात्मा परोच्चरेत् ।

उत्पत्तिद्वितयस्थाने भरणाद्भरिता स्थितिः ॥ २४ ॥

ūrdhve prāṇo hyadho jīvo visargātmā paroccaret ।

utpattidvitayasthāne bharaṇādbharitā sthitiḥ ॥ 24 ॥

Incoming breath

[into the heart]

is

[sounds]

Hammmmmmmm . . . [like the English word hum]

Outgoing breath

[exhaled to a distance of 12 finger-widths down from the tip of the nose into the space in front of the body known as bāhya dvādaśānta]

is

[sounds]

Sooooooooooooo . . .

Observe

their junctions

within

your heart

and outside . . .

Fullness results . . .

▼▼⛛ ▼▼

FREE INSTRUCTION AT LAKSHMANJOO ACADEMY

See also Swami Lakshmanjoos' commentary on Verses 166 – 156 of the Vijnana Bhairava Tantra in his Manual for Self Realization: 112 Meditations of the Vijnana Bhairava Tantra (pp. 268 – 270).

In the entire universe of wave vibrations, one the most intimate is breathing. Like a wave, our breathing rises and falls.

In Kashmir Shaivism, any seeming duality dissolves in the gap between breaths— when mental fluctuations are transcended. Thus, Cosmic Union can be experienced in the pause—between any two breaths—as pure Shoreless Awareness, Pure Consciousness.

▼▼⛛ ▼▼

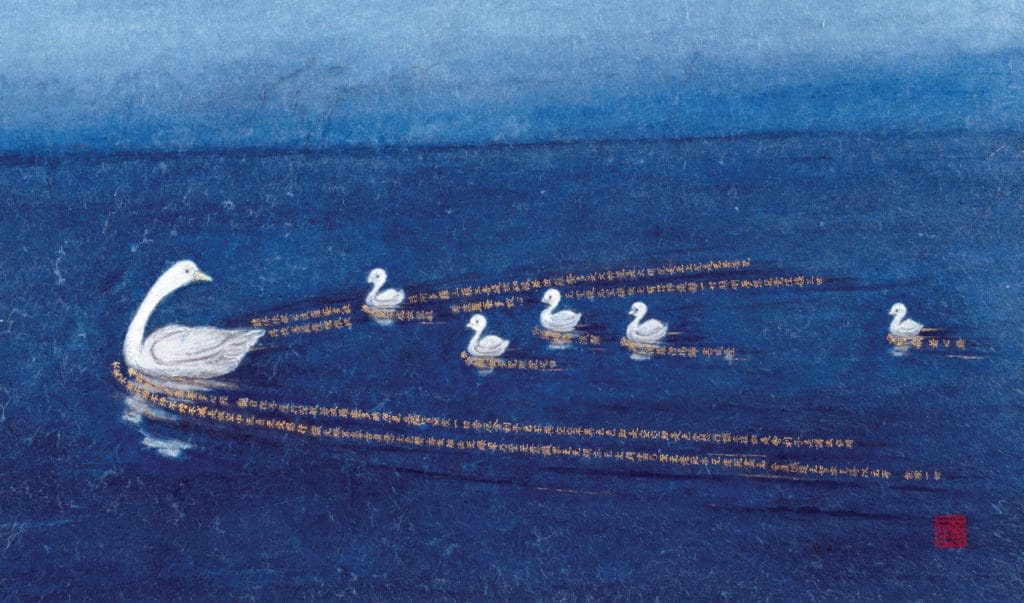

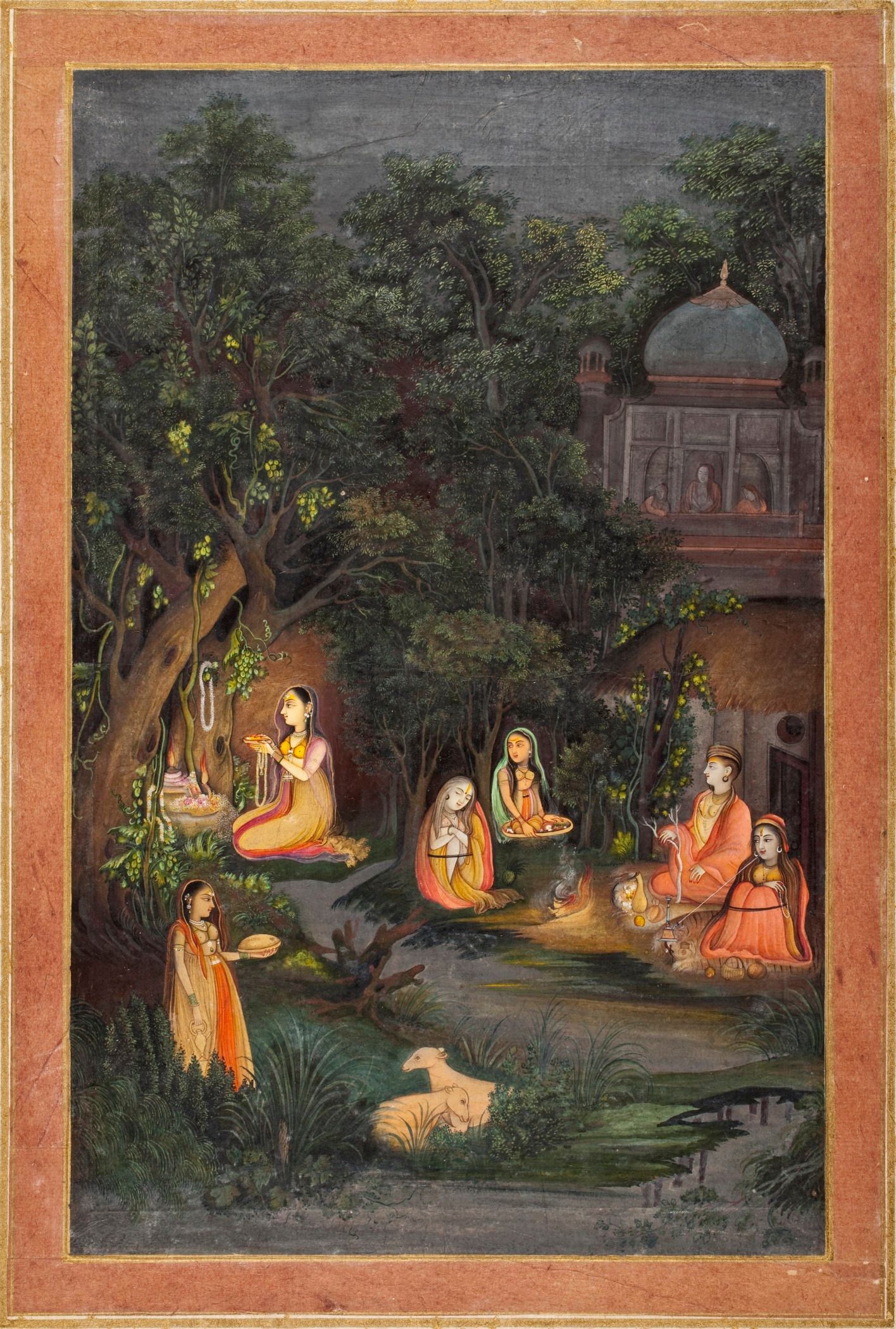

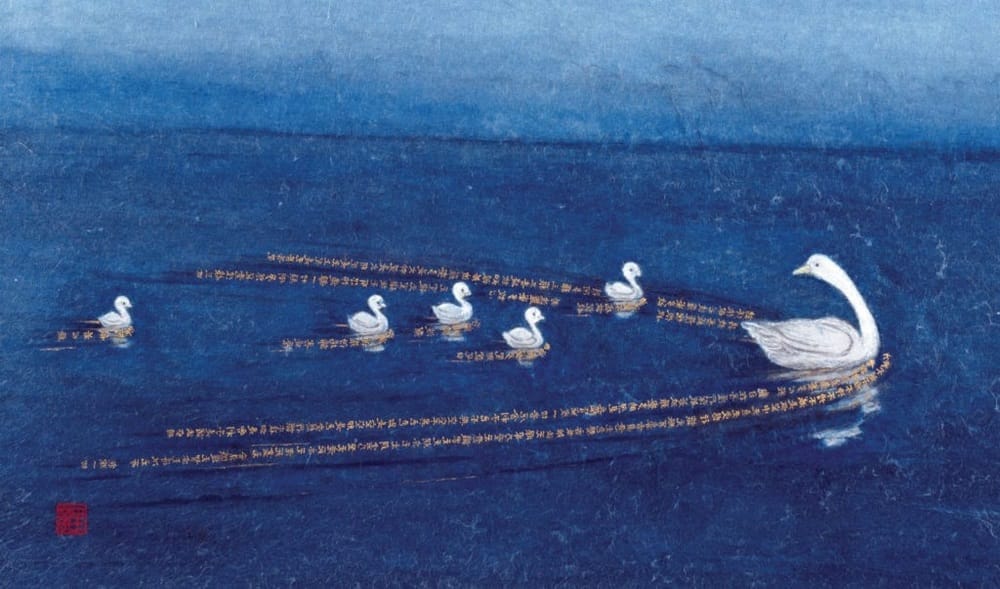

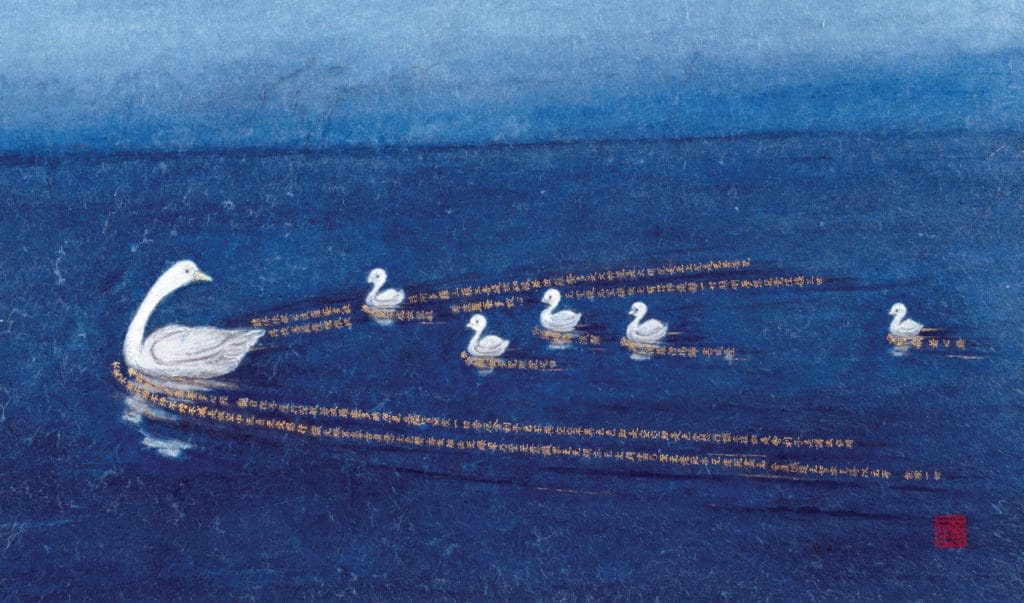

Drifting serenely across the tranquil mirror of the lake, the swan (haṃsa) glides with effortless grace, drawn to the radiance of a white lotus unfurling. Hovering in silent communion with the flower—between inhalation and exhalation—the creature plunges its elegant neck below the water's surface, savoring between breaths the sweetness of the milk within the lotus’s tender stalk.

Although the Sanskrit of this first meditation does not mention intoning the sounds Ham and So, in Swami Lakshmanjoo's commentary on the verse in his book The Manual for Self Realization: 112 Meditations on the Vijnana Bhairava Tantra (John Hughes, ed., pp. 32–33), he teaches that beginners should mentally intone Ham (which sounds like the English word hum) with the incoming breath and So with the outgoing.

Also, Swami Lakshmanjoo and Pandit Dina Nath Muju, in their 1974 — 1974 collaboration on this verse (above), focus on So and Ham, thus blending commentary into their rendering.

After all, according to Swami Lakshmanjoo, the scripture is meant to be a manual for masters in this tradition to instruct their students. Therefore, I leave that to Swamiji's teachings in his Manual for Self-Realization.

▼▼⛛ ▼▼

Note on Mental Pronunciation: In Sanskrit, the a in Ham sounds like the u in the English words cup and hum. Thus, Sanskrit Ham sounds like English hum.

In Sanskrit, the o in So sounds like the o in English so.

Traditionally, it is taught that with each cycle of breathing, the mantra so'ham (That I am) is mentally intoned: So in synchrony with the outgoing breath, and Ham with the incoming breath.

Swamiji further teaches that in this practice for beginners, the breath moves between two points: that of the inner, antara dvādaśānta and that of the outer, bāhya dvādaśānta (a dvādaśānta being a distance equal to twelve finger widths).

In his Manual for Self Realization, Swamiji discloses that the bāhya dvādaśānta is a point twelve finger widths from the center of the eyebrows.

To further clarify, in Jaideva Singh's The Yoga of Delight, Wonder, and Astonishment (YDWA), a note on this verse positions the bāhya dvādaśānta as "the point at a distance of twelve fingers [widths] from the tip of the nose in the outer space, where expiration arising from the center [heart] of the human body, and passing through the throat and nose ends" (p. 21).

To provide context, the glossary of YDWA describes five types of dvādaśānta. The first two are used in this technique: (1) A distance of twelve fingers from the tip of the nose in outer space is known as bāhya dvādaśānta and (2) a distance of twelve fingers from the bāhya dvādaśānta to the centre (hṛdaya) of the body is known as the antara (inner) dvādaśānta.

[The other types of dvādaśānta Singh lists are the following: (3) A distance of twelve fingers from hṛdaya up to kaṇṭha (throat). (4) There is a dvādaśānta from the palate to the middle of the eyebrows. (5) There is a dvādaśānta from the middle of the eyebrows to the Brahmarandhra. This is known as the ūrdhva (upper) dvādaśānta (running to the crown of the head). This distance is of use only when the kuṇḍalinī awakens. (Singh, p. 154).]

▼▼⛛ ▼▼

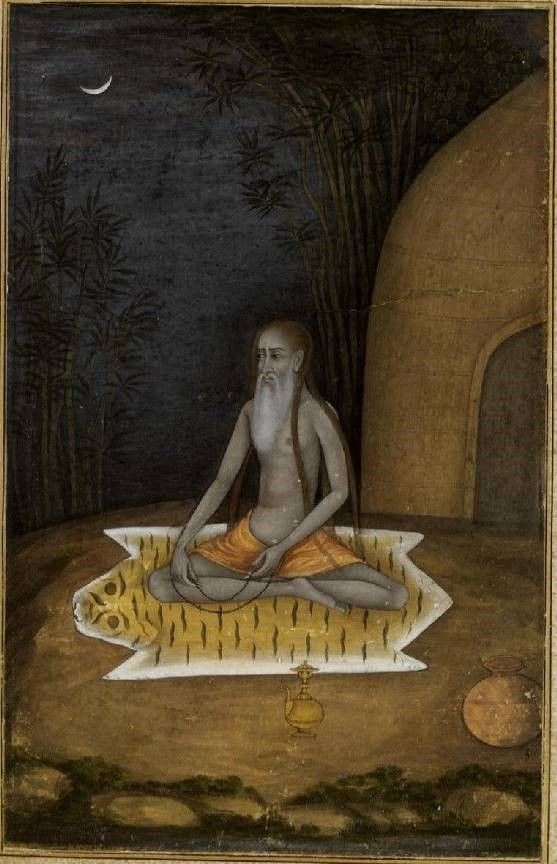

This system postulates three ways of realizing the Shiva State—the Ultimate Reality. In this tradition, Shiva is Unbounded Pure Consciousness.

Swamiji identifies this practice as suitable for those in the first stage: Āṇavopāya (Anav-upaya). The for-beginners stage of spiritual development.

• Anav-upaya is the method suitable for a limited being. It is meant for those who cannot yet rise above the interests of their limited selves and for whom the concrete and tangible is still more important than the abstract and intangible. So, in this method are included proper postures (asana), breathing exercises (pranayama), and repetition of sacred words (mantra). An aspirant on this path is usually required to concentrate on some symbol, such as triangle, Swastika, cross, or so on, or on some image, maybe of one's preceptor (guru), or of some deity, while repeating the sacred word given to one by one's preceptor. At a later stage, the preceptor may teach one to concentrate on the psychic centers in one’s body. If properly done, this can lead to the awakening of psychic faculties and even more, depending on one’s earnestness, purity of conduct, and the extent one can go beyond one’s limited self. This method is also called the method of action (Kriya-upaya).

• The next method, higher than the first, is called Śāktopāya (Shakta-upaya), or the method of Energy. Here, the external symbols and aids are dispensed with. No special posture or breathing exercise is considered necessary. Mantra is retained, but its verbal repetition is replaced by deep contemplation at a non-verbal level. The aspirant is required to contemplate so earnestly and with such awareness that the aspirant becomes one with the spirit of the Mantra and is permeated by its energy—for a Mantra is not merely a rhythmical arrangement of words, but a form of energy. Thus consciousness expands beyond the limited self. The greatest mantra is Hamsa (I am That). By contemplating the different facets of this mantra, the aspirant is led to negate the individual “I” and merge it into the universal “I.” This method is also called the method of wisdom (Jnyan-upaya) and is practiced long, even by the most advanced aspirants. It is considered quite capable of leading one to the next, which ushers in the highest Reality.

• The third and highest method is called Śāmbhavopāya (Shambhav-upaya), or the method of Shiva. At the first stage, bodily organs are involved in the various practices prescribed therein. At the second, bodily organs have no important role to play, as such, but the function of the mind at deep contemplative levels remains and has a very important role to play. Now, however, in the last state, even the mind has to be dispensed with. No rules can be laid down here, and no practices prescribed. Here, the aspirant’s only concern is to be in that state of awareness where the movement of thought comes to a stop. The only qualification is earnestness combined with deep, penetrative insight. Hence, this method is also called the method of will (Ichhopaya). With the cessation of thought processes, the state beyond mind dawns. To let it happen, suppression or sublimation of thinking is not the way, but rather an intense awareness of each thought and feeling, at all times (including during sleep) is needed. In this intensity of choiceless attention, the ending [or fading away] of any thought, feeling, or perception can result in the dawning of Enlightenment. When the cup is empty, something new can fill it.

Any method, however subtle, can be only a result of a thought process—a product of mind. Hence, it cannot touch that which is beyond thought, beyond mind. The mind can penetrate, at best, up to its own frontiers. Do what it will, it cannot go beyond its limits of time and space. Methods, one and all, are not only useless at this stage but rather obstacles. A method implies duality—a seeker and an object of search, a devotee and an object of devotion. The ever-present, all-pervading, all-knowing Totality needs not to be beseeched or coaxed. It arrives unsought, like a fresh breeze from the mountaintop, when the mind is free from thought and seeking.

When an aspirant comes to the clear realization of this fact, the Shambhav-upaya becomes An-upaya (No-Method) or what may be translated as Beyond-Method. In this state of non-dependence and effortless awareness, there is neither acceptance nor rejection, neither justification for nor identification with any feeling or thought. In this void, the worshipper is the worshipped. This state is not beyond action and wisdom only, but beyond will, too. It simply is.

II

Such is the path, yet there are hints available here and there, given out of compassion by those who have scaled the great heights, to help and encourage an earnest disciple to set his or her foot on the path. Shaiva Tantras are replete with such hints, though their esoteric meaning often remains obscure to those uninitiated in their mysteries. One of these, the Vijnyan Bhairava Tantra, is more explicit and expounds 112 unique ways of transcending the limitations of individuality. These ways are really meant for advanced seekers, who have reached that state of self-discipline where the need for laying down any formal discipline ceases. For such earnest aspirants, some situations likely to be met with in the ordinary course of life, and some practices—for performing which one need not withdraw from ordinary activities of life necessary for physical and social well-being—are delineated. Shaivism does not advocate external renunciation and running away from the world—for the cosmos is in Shiva and Shiva is in the cosmos. There is no situation where Shiva is not.

We cognize the external world by five senses—hearing, touch, sight, taste, and smell—which help us to gather knowledge, but which also, often, lead our minds astray. It is for this reason that usually all spiritual disciplines prescribe ways and means to curb and withdraw the senses from the world of manifestation. Shaivism here takes a radically different stand. It attempts to make these very senses and their pleasures stepping stones for the upward path: tasting, smelling, seeing, touching, and hearing. It elevates the pleasures of the senses from the plane of sensuality to that of increasingly refined sensitivity.

This approach appears, no doubt, alluring, but the neophyte must be forewarned. It is perilous too. An undisciplined, unwary, or overzealous beginner may easily stumble on the very first step and break his limbs. A very cautious approach is needed. A seriousness of purpose to realize the Truth and a whole-hearted devotion to it alone, form the prelude to this search. Plainly speaking, it is not meant for those who are still held by the desire for gross pleasures.

For Swamiji's further comments on this dhāraṇā, please refer to the Manual for Self Realization.

To enable his commentary on this scripture to flourish down through the ages, Swami Lakshmanjoo left it in two forms:

(i) a series of videos gracing each verse, which over a few years, John Hughes of the Lakshmanjoo Academy recorded, and

(ii) Swami Lakshmanjoo's textual embodiment of the tapes, The Manual for Self-Realization: 112 Meditations of the Vijñāna Bhairava Tantra (edited by John Hughes).

Both are treasures! In each, Swamiji comments on the scripture while responding to questions from his students. Swamiji emphasizes that the video version transmits his teachings with a higher level of fidelity.

![Self Realization in Kashmir Shaivism: The Oral Teachings of Swami Lakshmanjoo [Jan 10, 1997] John Hughes](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51oGUVi2AjL._SY385_.jpg)

▼▼⛛ ▼▼

More advanced meditators practice a second – a-japa (non-mantra) – technique associated with this verse. Following the principle that the techniques advance from more effort to less, in this more advanced technique, the incoming and outgoing breaths automatically "utter" the mantra. So one's attention remains simply on the moments of suspended animation between breaths.

See Swami Lakshmanjoo's commentary on Verses 166 – 156 of the Vijnana Bhairava Tantra in his Manual for Self-Realization: 112 Meditations of the Vijnana Bhairava Tantra (pp. 268 – 270).

One needs simply to meditate on the incoming and outgoing breaths—and their sweet, limitless junctions.

Because Swamiji envisions the ajapa practice as more advanced, he considers it to be not at all advisable for beginners.

Jaideva Singh, in The Yoga of Delight, Wonder, and Astonishment (YDWA), comments on both interpretations.

In addition to reading Lakshmanjoo's commentary in his Manual of Self Realization (John Hughes, ed.), reading Singh's notes on this verse is also certainly worthwhile if you are a practitioner in this system.

P.S. To get a feeling for how closely intertwined Lakshmanjoo and Dina Nath's native tongue, Kashmiri, is to Sanskrit, consider that in Kashmiri, the feminine noun azapā (Sanskrit, ajapa) denotes the following: a certain mantra or mystic formula which is not uttered but which consists only in a number of inhalations and exhalations.

Kashmiri has many Persian loan words as well.

Swami Lakshmanjoo and Pandit Muju's original reads as follows:

Verse 24

The ingoing breath is (sounds) Ham and outgoing breath is So. Observe their junction both within your heart and outside. Fullness results.

Ψ

▼▼⛛ ▼ ▼

On the South Asian subcontinent, the haṃsa (swan or goose), a migratory waterfowl, is believed to be endowed with a near-alchemical ability: the capacity to separate milk from a mixture of milk and water. Scholars speculate that this attribute originates from the bird’s behavior—gliding gracefully upon a lotus-strewn lake, it delicately extracts milk-like nectar (kṣīra, meaning ‘milk’) from the fibrous submerged stalks of lotus plants.

Thus, the poetically imagined prowess of the haṃsa escapes mere ornithological observation by blossoming into metaphor. Within the cultural and spiritual traditions of the region, the hamsa serves as a symbol of spiritual discernment. Just as the haṃsa is imagined as isolating milk from a blend of milk and water, so too does the yogi(ni) realize the singular, essential truth of boundless consciousness indwelling all phenomena.

In Yoga and the Hindu Tradition (1977), Jean Veranne expounds on the

direct phonetic-symbolic link between the act of breathing and the name of the migratory bird [hamsa]. When we breathe in, the text asks, does not the air as it enters make the sound ham? And when we breathe out, does not the air hiss as it leaves, making the sound sa? So that we are all of us, however unwittingly, forever repeating hamsa! hamsa!

The air goes in making ham! [sounding like the English word hum]

It goes out making sah!

So the living being lives life

repeating endlessly

the mantra of the bird!

One needs only to become aware of this

to be free from all sin.

(Dhyanabindu Upanishad)

. . . .

It should be added that the same two syllables in reverse order (with a slight phonetic change required by the rules of Sanskrit grammar) mean something quite different: so'ham, so'ham (I am It, I am It!") we also all proclaim as we breathe, and "It," needless to say, is hamsa, the Atman. Again, moreover, consciousness (a real, effective, experienced consciousness) of the secret meaning of the two syllables so'ham has a liberating power. By repetition of this new mantra (esoterically identical with the first), one obtains liberation because one is realizing the identity of the self and the inner controlling force (antar-yamin)—yet one more name of Atman-Brahman. Combined, the two mantras are an encapsulation of the entire doctrine: "My true self is the Atman there in the deepest heart of myself!"

[Ham, again, sounds like the English word hum.]

In the 15th- or 16th-century, the Hamsa Upanishad (Haṃsopaniṣad) appeared.

As one of the Yoga Upanishads, the Haṃsa Upanishad teaches that the haṃsa dwells not only upon lakes, but within us, entering us at birth and residing within us hidden away—like fire in wood or oil within the sesame seed.

The Upanishad begins as follows:

Sage Gautama, approaching the Lord, asked him:

1. You who know all the laws, you who know all the sciences, tell me, Lord Siva, how to awaken the mind to the knowledge of Brahman.

To which Siva replied:

2. First, learn the laws, and thoroughly assimilate the teaching of the Lord of the Trident, only then, Gautama, will I tell you the Truth as revealed to me by the Mountain Goddess.

3. This truth is secret, it must not be divulged. I reserve it for the perfect adept, for whom yoga makes a jewel case worthy of the finest jewels. It is the true knowledge of So-Ham, and through it, one obtains freedom forever.

4. So I will tell you what this doctrine is and what Ham-Sa and Para-Hamsa are because you are a self-controlled (celibate) novice devoted to study. The teaching is that one must meditate again and again on the Ham-Sa, continuously repeating Ham Sa Ham Sa . . .

5. He enters into all beings, the Ham-Sa, the Atman, and becomes present in them like fire in friction sticks, like oil in sesame. To know this is to conquer death.

6. The adept, first of all takes the lotus posture and tints the breath he inhales; then pressing his anus with his left heel, he causes the breath to rise from the center of the base to the door of the jewels, not without having led the breath to revolve three times around the Svadhisthana; from there the breath rises to the Anahata and passes it, gaining the Vishuddi, which is flanked by two balls of flesh similar to testicles; still holding the breath, the adept then leads the inhaled air to the Ajna-chakra and the Brahmarandhra; meditating, he finally realizes that he is the one with three letters, Om. He [the triad]: Being, thought, and bliss—beyond all form.

7. He is the supreme Ham Sa, resplendent with the light of ten million suns, and by whom all things have been penetrated.

8. Now dwelling in the lotus of the heart, he finds there eight incitements corresponding to eight petals: the eastern [Orient] petal inclines toward pious actions. The petal of Agni inclines toward slumber, to laziness, and the petal of Yama, to cruelty. The petal of Nirrti incites wrongdoing. In Varuni, the Goddess lies in thirst of pleasures, and in Vayavi, the desire to travel. The petal of Soma inclines toward sensuality, and that of Isana the pursuit of material goods. In the middle of the lotus lies the disgust that follows satiety, and the stamens govern the waking state, the pericarp governs the state of light sleep, and the androecium governs deep sleep. As for the fourth state, Ham reaches it when he leaves the lotus.

9, It then goes even beyond this fourth state when within it the resonance—which circulated throughout the subtle body from the center of the base to the Brahmarandhra—is extinguished like the song of a pure crystal. This resonance is said to be Brahman, the Supreme Soul.

10. Of this mantra, Ham-Sa is the Seer, the meter Gayatri, the dedicatee Parama-Hamsa, the verbal seed, Ham, is the seed syllable (bija), it is He. So is his Shakti (his power) and Ham-Sa (So Ham) the sharp point: I am He!

11. This mantra must be repeated twenty-one thousand six hundred times, meditating on the six centers night and day, dedicating this meditation to the sun and the moon, the impassive Lord, and the unmanifest Brahman. We will thereby incite the subtle and formless element which is deep within us.

12. This mantra we use for the touching rites, starting with the heart, we continue to all the members by repeating the ritual interjection: vausat for Agni and Soma;

13. At the end of the rite, we meditate on Ham-Sa nestled in the cave of the heart, that is to say, in the Atman.

13. Of this bird, Agni and Soma are the wings; Om is the head, of which AUM and the bindu of Om are the three eyes and his face. Rudra and his consort are the two legs; such are the representations that are used in the double rite performed from the throat; the close union between the Hamsa and the Parama-HamSa (Self and Self) is accomplished in two stages, the dual union and the absolute union.

14. At the conclusion of this rite, the ajapa mantra ceases where the beyond of thought begins. [Unmani which means absence of thought. In the end of the rite, we meditate on Ham Sa nestled in the cave of the heart, the heart of the heart, the Atman.]

15. One can also cognize the sound by repeating the mantra ten million times; the sound then manifests itself in ten ways as follows: we first hear chin, then secondly chini, chini; the third sound is that of a bell; the fourth of a conch shell; the fifth of a string; the sixth of a cymbal, the seventh of a flute, the eighth of a drum, the ninth of a bass drum, the tenth finally is that of thunder.

16. We must neglect the first nine sounds and concentrate our attention on the tenth, which is that of thunder.

17. At the first sound, the body of the adept sounds chin chini; in the second, this disappears; at the third the lotus of the heart is pierced; at the fourth, the head trembles; at the fifth, the palate oozes; in the sixth, ambrosia is drunk; in the seventh, we see the mystery; in the eighth, the word is heard; in the ninth, the body becomes invisible and the divine eye opens, without defilement; it becomes Brahman at the tenth, achieving the union of the soul and Brahman.

18. From then on, and by this very fact, the individual mind is destroyed, which is the source of thoughts and desires like images and mental constructions (sankalpa and vikalpa); then, from the cessation of these two activities of the mind but also from the extinction of positive and negative acts, is born the transfiguration of the disciple into Sada Shiva, (literally the always Shiva) the revealer who shines of the nature of Shakti, the Omnipenetrating, which is in essence radiant splendor, which is the immaculate, the eternal, the pure, and the supremely peaceful Om.

[End of Upanishad]

Ѱ

You who let yourselves feel:

enter the breathing

that is more than your own.

Let it brush your cheeks

as it divides and rejoins beside you.

Blessed ones, whole ones,

you where the heart begins:

You are the bow that shoots the arrows

and you are the target.

. . .

Sonnets to Orpheus, Part One, IV

Ranier Maria Rilke

trans. Macy and Barrows

The Swan, 1914 – 1915.

Viewed in sequence, the series has a distinct visual rhythm. Often a horizontal line breaks the canvases into two sections where opposite forces meet – light and dark, male and female . . . .

These poles unfold as a black and white swan. Eventually, figuration gives way to abstraction in a fuller spectrum of colour. In the final work in the series, the swan pair returns, unified at the centre, intertwined yet distinct and balanced as male and female poles (text: Moderna Museet).

Stockholm Sweden