meditation 107

Realize firmly

all this

[all that is / this entire universe / including all these mental constructs / including this very verse]

as unreal —

like a magic show.

You go to

Eternity.

Notes:

This is verse 133.

*

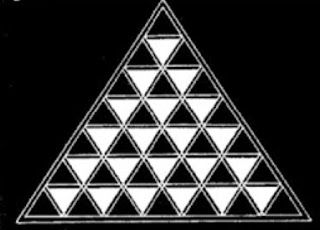

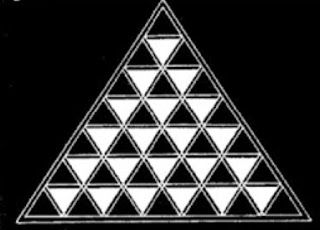

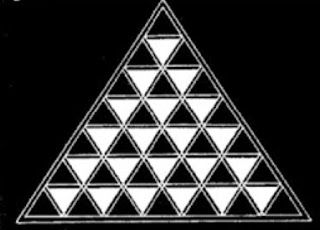

If you feel so inclined,

imagine you are Dadealus entering the laybrinth!

and for a while,

and without getting too lost in there,

gazing into the waves of magically arising

and dissolving triangles of the Minotaur's

horns!

What is your raw,

immediate, first reaction?

A feeling of being flabbergasted:

bewondered,

bewildered,

delighted!?

Now imagine yourself in medieval Kashmir

you are out for the evening,

taking in a dance performance . . .

of . . . Wait!

This cannot be happening!

. . . . a dance performance of Cervantes' masterful novel, Don Quixote.

When you realize that the Medieval Era in India was hundreds of years before Cervantes, you will probably pinch yourself, scream This does not compute! — and abandon yourself to wonder!

Lost in wonder, you will have ceased computing.

For in Indian aesthetic theory, wonder is one of the primary emotions.

Wonder is seductive — like the following magic show:

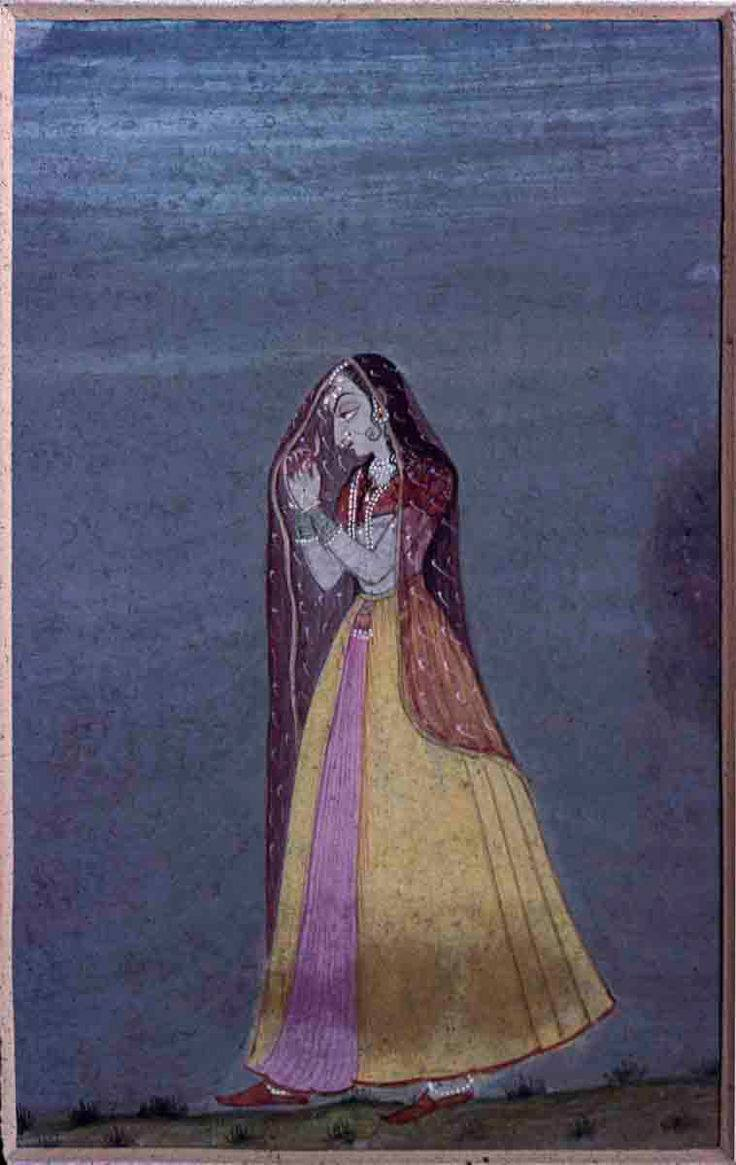

In Indian aesthetics, though, the primary-most emotion is shanta – peace – as in this:

The aesthetic experience of tasting peace, shanta, is thought to offer the flavor of ontological shorelessness, thought-free pure awareness: the peace one abides as in deep meditation. Shanta, however, is not merely aesthetic. It partakes of Being (the) ontological and something like salvation (the soteriological).

^^

A second aspect of magic is that it is based on an illusion: a trick.

One must also consider that Pandit Muju was originally a believing Theosophist, who then witnessed and then espoused J. Krishnamurti's rejection of belief and therefore the entire edifice of the Theosophical worldview.

When flabbergasted by a magic trick, after the astonishment fades away, one realizes it had been only a trick, an illusion, not real.

If it is true, it is false. If it is false it is true.

Like Dubois, I feel the "all this" of the verse refers to the entire universe, and thus to all of the 112 ways delineated in the scripture. In doing so, this verse reveals itself to be one of the verses in the scripture that is meta-verse. It applies to all scripture's verses, including itself.

Perceived in this light, the logic of the verse echoes that of Bhartrihari's Paradox: All I have said is a lie.

If it is a lie, it is true. If it is true, It is a lie.

If this verse on magic applies to itself, then its statement that everything is only a trick is also only a trick.

If the statement is real it's not real. If the statement is unreal, then it's real.

And if it applies to all the other ways in the scripture, they are all in the same hat.

A paradox often leads the mind to a state of aporia, a felt sense that it has no path forward.

This is not a bad thing but a good one.

In fact, the scripture opens with the Goddess posing as one who confesses she is not able to understand the teachings of the tradition. And her aporetic state leads to an unfolding of the 112 ways.

So this is a second way of looking at the magical waves of triangles. There must be some kind of trick going on, some optical illusion, because it is impossible for triangles to physically move about within the image.

It is as though a magician leads the whole world to believe that a rope is a snake! But it is not a snake, only a rope.

This second response, though, is the one that Swamiji, in the Manual of Self Realization, seems to adopt in his comment on this verse. The rope–snake metaphor, however, is typically Vedantic rather than Tantric.

The following is my guess why Swamiji would gloss the verse in this more skeptical way, a way that to Dubois and Wallis seems puzzlingly more Vedantic than Tantric:

First, Medieval Kashmir, situated on a nexus of the Silk Road, is both insular and cosmopolitan and eclectic. The collection of ways the scripture presents is a synergistic compendium of techniques and philosophical attitudes, including those of Buddhist and of course Vedanta-oriented viewpoints.

Second, in my understanding, Kashmir Shaivism understands various understandings as arising from within the play of the consciousness. And Lakshmanjoo and Muju parenthetically delimit the all this of this verse to all these mental constructs.

Speaking of which, a third response to this verse could be Buddhist.

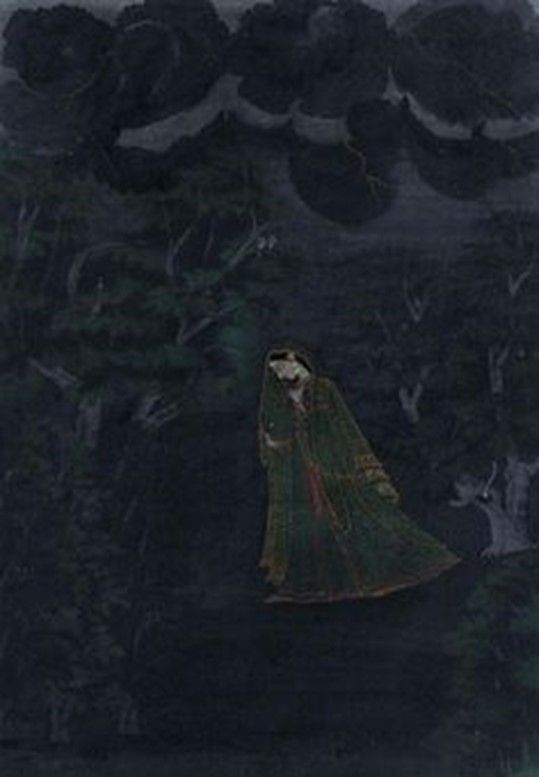

Again, meditating, a few minutes on the above “cloud’s” convolutions, do you not notice how haunting, how ghost-like, these figurations of presence-absence, ever shifting — arise?

How these convolutions of clouds "present" themselves by erasing all former "presences," then dissolving, into nothing as fresh formations float into vision?

How each so-called cloud's forming depends upon and bears within her form the traces of past and future clouds? How — as soon as there “is” some “thing” to see "there" – "it" will have always already been swallowed?

How there will never have been any central configuration of clouds that could be penned in with a capital C ?

From a Buddhist perspective, all "things" are interdependent arisings, devoid or empty of inherent inexistence, of thingness.

Essentially nonessential, they are structurally empty.

The scripture, though, seems to view emptiness as a thing: the Void.

EmptiNESS.

Like Nessie, who is nothing only coincidentally.

One must also consider that in the Manual of Self Realization, Swamiji states that the all of this of this verse applies to all of these 118 worlds. But that these 118 worlds do not exist.

If the scripture resides in this world, we can conclude, then, that the all this of this verse applies equally to all the 112 ways (all these mental constructs the scripture offers), including this "present" one.

Shunyatashuntaya. The emptiness of emptiness.

In this Buddhist philosophy there is a higher truth, that of emptiness, and a lower truth: that of conventional day-to-day reality.

The teaching is, though, that if one makes too big of a deal of the higher truth, one disfigures it to the point that it becomes the lower truth.

Nagarjuna saw intellectual clinging as the most insidious form of clinging, and thus of suffering.

This is why an aporia, when the mind finds no path forward – as with Arjuna on the battlefield or a zen student befuddled by a koan – opens the way easy to illumination.

As they say in zen: If you understand, you don't understand.

Aeons ago, in the mountain vale of Kashmir, in the effortless way lakes reflect night's flow of galaxies, a procession of yogic subtleties appeared.

This yoga of subtleties is not a staid, stolid, mapped-out mental exposition. She is not an unyielding, orthodox, dogmatic, eyes-clapped-shut mental exposition.

She is not a building up, like the erection of a theological system.

She is a licking away, a melting, a lingo of erosion.

She might be snow-blindness, bleaching away our vision of this world.

She might be monsoon darkness, eroding away all forms into a sable sense of shoreless union.

Her roots do not fail, for she is a fast-rooted, dancing tree, a yoga anchored neither in Sky nor Earth but in precisely no place in particular.

She dances into each truly living moment of one's life: a djinn or genie flailing rhapsodically her thousand-thousand arms, pounding out silent rhythms at full-universe scale.

Like a magician, she offers high-wattage, fun, unfussy, vertiginously alluring gardens of awe.

She perceives the world not as solid, but as a web woven of wonderments: of breathtaking astonishment: delight swooning, flickering, fading, dissolving, evanescing, into awakening.

She teases forth our sensitivities to spirit-like impalpabilities . . .

These beckon from within the dark emptiness within water pots and village wells, from within the silence-haunted sounds of the alphabet, from the nothingness indwelling the unending spaciousness of blue sky and all-absorbing darkness, from the silences before and after lightning, from the voids within the circles of peacock feathers, from the boundless space within the heart, from between inhalation and exhalation, waves of mind and their troughs, before and after notes of melody fading away on stringed instruments, before and after the intense delight and astonishment or being tickled and loved, and sweet remembrances of such joys, or the the warmth of reunions, or when immersed within the sounds of misty waterfalls or rapid, thundering rivers, waking fading into sleeping, or when swaying side to side, bouncing up and down — skipping — the vast void of space, before and after a bee’s prick, before and after desire, when awed by a magician’s trick, when lost within puzzles or aporiae, at the beginning and end of sneezing, sorrow or sighing, keen curiosity or hunger, or when intense devotion melts into union . . .

Within each fading, each unknowing, dwells something worth knowing. Something that does not struggle to refill the veiled moon with light but, like darkly turbulent convolutions of monsoon clouds, bleeds into midnight-layered veils of bliss-bruised blackness: blackness fractured and interlaced with deep, golden veins of electrified now-ness.

Unknowing is a kind of monsoon yoga, opening to gaps within the seemingly solid convolutions of time: to liftings, like a magician’s pause — wand poised above ephemeral peanut shell — disclosing neither common legume nor coin, but a nothingness poised within all points of all of eternity’s wondrous hatchings.

For at her best, awareness is not stone, but impish, nymph-ish creation in mid-chaos and stillness: one more impasse, one more node of the lotus blooming into inaudible thunder, seeking ever new points of suspension.

A yoga of unknowing requires a certain negative capability, a capacity for drifting within the thin aether of obscurities, uncertainties, riddles, aporiae, mysteries, doubts — without any anxious grasping after facts and reasons.

She is the yoga of voids, of absences blooming up between the cracks between tones, breaths, moods, moments, sips, dreams, kisses, modes of being, ripples of light spreading across the space of the heart, the patterns of lisping patters of rain, peacocks piping pea-pea pew-pew-pew amid the amorous effluvia of monsoon downpour.

For the solid mass of monsoon blackness is forever moving and folding over within her own utter penetralia — with pauses in her misty figurations—dramatic, fractured with fissures, lightning gasps, inter-undulatory naughts, abysses ever-roiling within convolutions of awareness.

Again, meditating a few minutes on the above “cloud’s” convolutions, do you not notice how haunting, how ghost like figurations of presence, ever shifting — arise? How they "present" themselves by erasing all former "presences," then dissolving, as fresh forms float into vision? How each so-called cloud depends upon and bears within her form the traces of past and future clouds? How — as soon as there “is” some “thing” to see "there," "it" will have always already been swallowed? How there will never have been any central configuration of misty cloud that could be penned in with a capital C ?

How the only real presence — fleeting — among all these enfoldings, fading convolutions, pauses between waves — is pure, vibratory awareness — flashing?

How — like listening to rain — your own awareness assumes a body of steam, your face of mist, your hair, of unhurried lightning, crossing this cloud bank and entering this pause . . . ?

How — floating, frolicking, leaping between undulations — awareness swallows itself, like an ephemeral fish?

Gazing again, do you notice: the less you grasp at the risings and fadings away, surrendering to their flow, how mist rises, walks away, how fissures flash forth in larger swallowings — formless, luminous, weightless?

Awareness a fish leaping in the green body of river reeds, a poetics of mute thunder melting into the penumbra of a voiceless, formless silence, a Goddess of silence-haunted syllables, her toes curling into rain, her fingers entwined within your own.

She is lightning, appearing from clouds, born from rain, clothed in rain — leaping from chakra to chakra.

For she is hidden — like a gardenia within cascading ebony tresses. Her eyes are of rain, her waist of water, her embrace a current. She rushes into river, floating away, one night, O human child, with your heart.

To find her — a thousand years ago — in May, hugging the Malabar Coast: lustrous, fresh blossoming — sandbanks white dunes with masses of pearls scattered “there” by incessant waves.

As you sail up the coast, lustrous naïve young women lifting up their questioning faces, will — with rapt eyes — drain deep draughts from your heart.

When cool, moisture-laden winds gush through your hair, when the sky darkens to peacock feather pitch, when solid sheets of water fall from sable, seething clouds, when the universe of vegetation sways and writhes in plundering embraces of monsoon winds — young lovers dip their brushes, their hearts bleeding inky love notes, amorous cumuli melting into one another in posesies as passionate and piquant as poses are manifold.

As sunless daylight sinks into moonless night, young women burn jasmine incense sticks which — dying — keep raising their ash-soft necks to humid kisses of night air.

Abandoned to monsoon darkness, to world-swallowing night, to darkness thick enough to touch — young maidens wonder. Has the broad shadow of the body of some divinity erased the world?

Has the sky, its soft, thundering folds swallowed Earth with all her seas and mountains?

Fawn eyed, before themselves they behold only blackness. Draped in sable silk, body scented with sandal and musk, neck encircled with black sapphire necklaces, ears dangling inky peacock feathers, they steal away to their secret rendezvous.

~

Swamiji and Panditji's original reads as follows:

Realise firmly that all this (that the mind constructs) is evenescent like a magic show. You go to Eternal.