meditation 3 : verse 26

न व्रजेन्न विशेच्छक्तिर्मरुद्रूपा विकासिते ।

निर्विकल्पतया मध्ये तया भैरवरूपता ॥ २६ ॥

na vrajenna viśecchaktirmarudrūpā vikāsite ।

nirvikalpatayā madhye tayā bhairavarūpatā ॥ 26 ॥

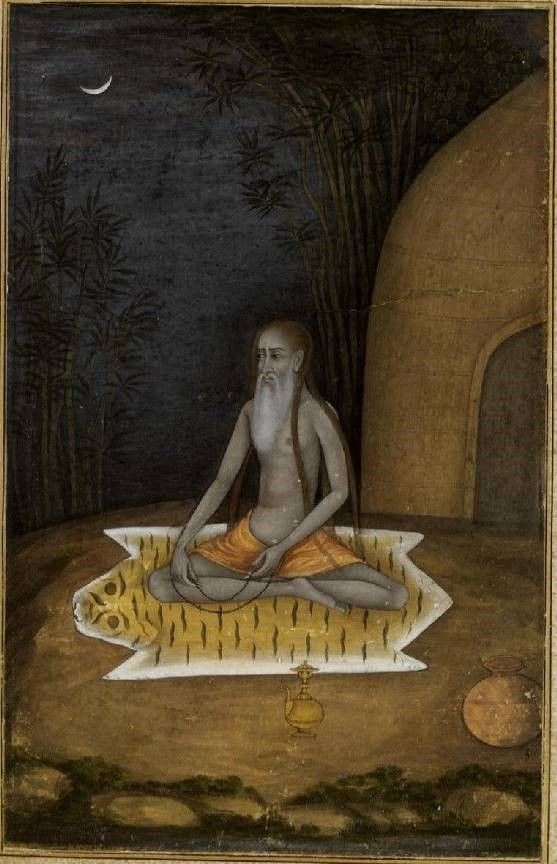

When mind

is silent . . .

and breath

ceases

flowing . . .

in

and out . . .

it stays

of its own accord

in the center . . .

Watch the moment.

Divinity dawns . . .

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

Swami Lakshmanjoo and Pandit Dina Nath Muju's original reads as follows:

Verse 26

When the mind is silent and breath ceases to flow in and out, it stays of its own accord in the centre. Watch the moment. Divinity dawns.

Ψ

Enticingly, Jaideva Singh notes that when awareness is absorbed within the "pause" [void] between breaths, spontaneously prana abides within the Central Channel (the suṣumnā).

According to Lakshmanjoo, this verse does not describe a technique.

Rather, it portrays awareness reposing in its blessed self-referral state, with prana suspended in the Central Channel and thoughts transcended.

Again, in this state, when thoughts still (in nirvikalpa bhāva), the prana usually coursing through the intertwined Moon (ida) and Sun (pingala) channels, enters the Central Channel (suṣumnā).

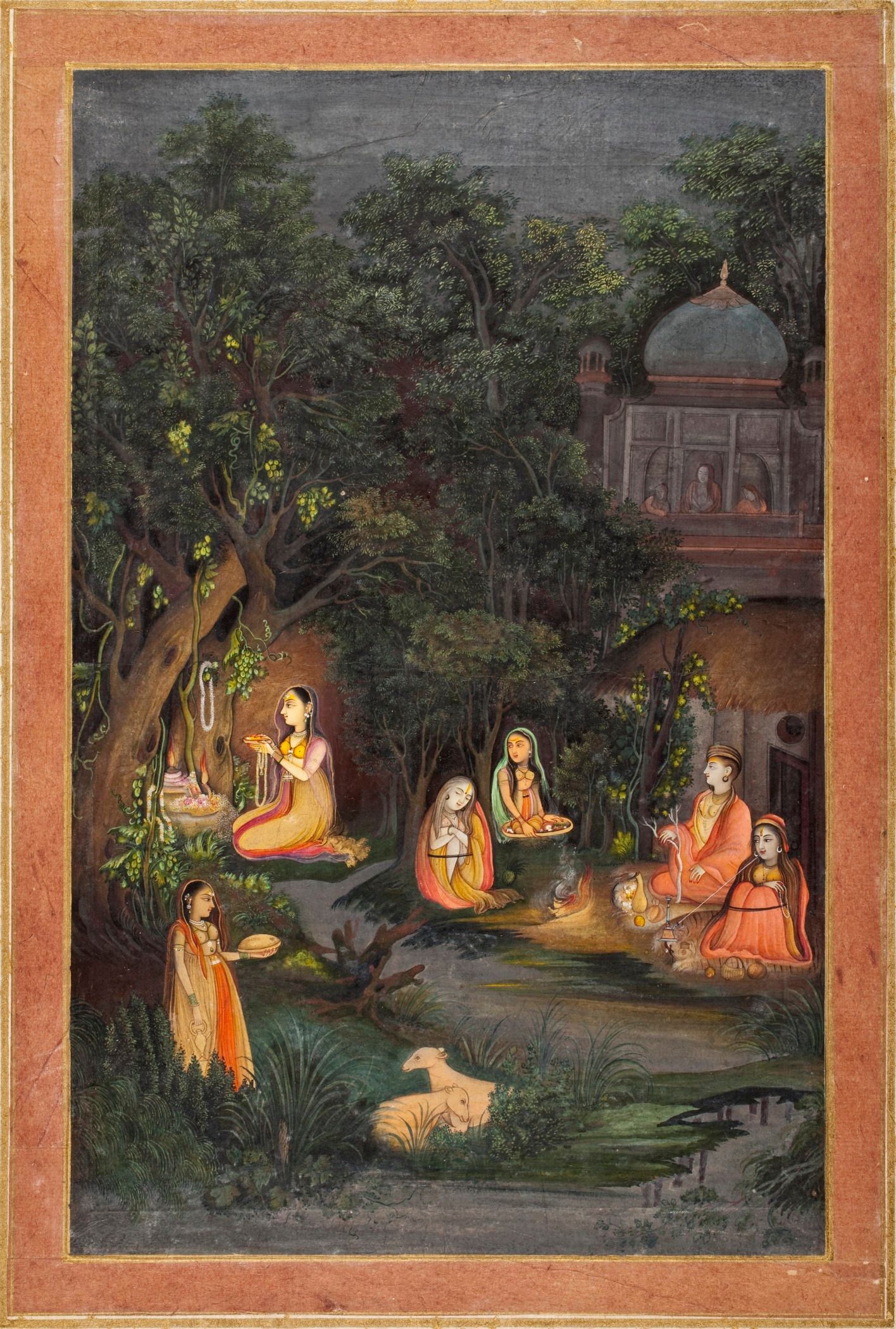

Śivopādhyāya comments that the still mind free of thoughts (nirvikalpa bhāva) is Bhairavi mudra: a state wherein awareness abides as Shoreless Consciousness even as the senses are turned outwards, as when Bhairava and Bhairavi embrace within the heart of breathless transcendence.

This makes it possible to experience the union of inhalation and exhalation even within the warmth of a subtle embrace, as described in Verse 69 of the scripture, which, according to Swami Lakshmanjoo and Pandit Dina Nath Muja, describes sexual union of enlightened couples as subjective rather than objective.

Their 1974 – 1975 teaching on Verse 69 reads as follows:

Perceive the pleasure arising

by giving expression to sexual behavior

as subjective

rather than objective . . .

Bliss overflows.

Neither Verse 26 (describing the union of breath in the Central Channel) nor Verse 69 (describing the union of an enlightened couple) portrays a means or a technique (dhāraṇā).

They both portray an enlightened state of union within the Shoreless, Self-referral State . . . a union of Consciousness within Consciousness.

For the pre-enlightened, Verse 28 applies:

Whatever activity

you are engaged in . . .

and wherever you are . . .

be aware . . .

of the interval . . .

between two breaths.

Before long . . .

an extraordinary state

will dawn . . .

Touching upon the subjectivities of these verses are some words of Tibetan writer-translator Zhangzhunpa Chöwang Dragpa, who in the 15th century rewrote (in verse form) a prose biography of the Great Translator Rinchen Zangpo (958 – 1055 CE), who was a master translator of Indian Buddhist texts into Tibetan.

His original prose biography, an account of a journey, appeared in the same period as the Vijñāna Bbhairava.

At one point, Rinchen Zangpo was in Kashmir. In Zhangzhanpa Chöwang Dragpa's verse "reworking" of the prose biography, some lines appear to subtly allude to the yogic unions of local couples.

Wouldn't it be nice if the translator were still around to field our questions?

The boys of bliss

are skilled in embracing

their girlfriends of emptiness.

. . .

Sun and moon, robbed of their wind-steeds,

what have they to ride on

but the Central Channel?

And what they enter is the palace of union,

a combination path traversed in an instant.

Even contemporary couples who have lived lives devoted to transcendence often describe their love as subjective rather than objective, as Lakshmanjoo teaches.

Lakshmanjoo has also said that the fullness of such a state of union is possible only for the enlightened.

Dan Martin, who translated Zhangzhunpa into English, informs us that "the context here, being yogic, surely refers to the Central Channel of the subtle body. Successful yoga practitioners, whether Buddhist or Nath, dissolve the solar and lunar currents into the Central Channel."

See: VEIL OF KASHMIR: Poetry of Travel and Travail in Zhangzhungpa’s 15th-Century Kāvya Reworking of the Biography of the Great Translator Rinchen Zangpo (958 – 1055 CE), by Dan Martin

Reader's may have noticed there is no mention of the location of the central channel.

Abiding as Shoreless Awareness, prior to language and symbols, the wholeness of life within Being transcends time-space and signification.

When breath and thought pause, the Center blooms of itself.

Kashmir Shaivism postulates three ways of realizing the Shiva State—the Ultimate Reality. Swamiji assigns some practices of the scripture to those in the Āṇavopāya (Anav-upaya; for-beginners) stage of spiritual development. The next method, higher than the first, is called Śāktopāya (Shakta-upaya), or the method of Energy. The third and highest stage is called Śāmbhavopāya (Shambhav-upaya), or the method of Shiva.

Because in this dhāraṇā there is no mantra, no breath—only thought-free awareness in the central channel—Swamiji assigns this dhāraṇā to the Śāmbhavopāya way of realization, the most effortless way.

• Anav-upaya is the method suitable for a limited being. It is meant for those who cannot yet rise above the interests of their limited selves and for whom the concrete and tangible is still more important than the abstract and intangible. So, in this method are included proper postures (asana), breathing exercises (pranayama), and repetition of sacred words (mantra). An aspirant on this path is usually required to concentrate on some symbol, such as triangle, Swastika, cross, or so on, or on some image, maybe of one's preceptor (guru), or of some deity, while repeating the sacred word given to one by one's preceptor. At a later stage, the preceptor may teach one to concentrate on the psychic centers in one’s body. If properly done, this can lead to the awakening of psychic faculties and even more, depending on one’s earnestness, purity of conduct, and the extent one can go beyond one’s limited self. This method is also called the method of action (Kriya-upaya).

• The next method, higher than the first, is called Śāktopāya (Shakta-upaya), or the method of Energy. Here, the external symbols and aids are dispensed with. No special posture or breathing exercise is considered necessary. Mantra is retained, but its verbal repetition is replaced by deep contemplation at a non-verbal level. The aspirant is required to contemplate so earnestly and with such awareness that the aspirant becomes one with the spirit of the Mantra and is permeated by its energy—for a Mantra is not merely a rhythmical arrangement of words, but a form of energy. Thus consciousness expands beyond the limited self. The greatest mantra is Hamsa (I am That). By contemplating the different facets of this mantra, the aspirant is led to negate the individual “I” and merge it into the universal “I.” This method is also called the method of wisdom (Jnyan-upaya) and is practiced long, even by the most advanced aspirants. It is considered quite capable of leading one to the next, which ushers in the highest Reality.

• The third and highest stage is called Śāmbhavopāya (Shambhav-upaya), or the method of Shiva.

At the first stage, bodily organs are involved in the various practices prescribed therein.

At the second stage, bodily organs have no important role to play, as such, but the function of the mind at deep contemplative levels remains and has a very important role to play.

Now, however, in the last state, even the mind has to be dispensed with. No rules can be laid down here, and no practices prescribed. Here the aspirant’s only concern is to be in that state of awareness where the movement of thought comes to a stop.

The only qualification is earnestness combined with deep, penetrative insight. Hence, this method is also called the method of will (Ichhopaya).

With the cessation of thought processes, the state beyond mind dawns. To let it happen, suppression or sublimation of thinking is not the way, but rather an intense awareness of each thought and feeling, at all times (including during sleep) is needed. In this intensity of choiceless attention, the ending [or fading away] of any thought, feeling, or perception can result in the dawning of Enlightenment. When the cup is empty, something new can fill it.

Any method, however subtle, can be only a result of a thought process—a product of mind. Hence it cannot touch that which is beyond thought, beyond mind. The mind can penetrate, at best, up to its own frontiers. Do what it will, it cannot go beyond its limits of time and space. Methods, one and all, are not only useless at this stage but rather obstacles. A method implies duality—a seeker and an object of search, a devotee and an object of devotion. The ever-present, all-pervading, all-knowing Totality needs not to be beseeched or coaxed. It arrives unsought, like a fresh breeze from the mountaintop, when the mind is free from thought and seeking.

When an aspirant comes to the clear realization of this fact, the Shambhav-upaya becomes An-upaya (No-Method) or what may be translated as Beyond-Method. In this state of non-dependence and effortless awareness, there is neither acceptance nor rejection, neither justification for nor identification with any feeling or thought. In this void, the worshipper is the worshipped. This state is not beyond action and wisdom only, but beyond will, too. It simply is.

II

Such is the path, yet there are hints available here and there, given out of compassion by those who have scaled the great heights, to help and encourage an earnest disciple to set his or her foot on the path. Shaiva Tantras are replete with such hints, though their esoteric meaning often remains obscure to those uninitiated in their mysteries. One of these, the Vijnyan Bhairava Tantra, is more explicit and expounds 112 unique ways of transcending the limitations of individuality. These ways are really meant for advanced seekers, who have reached that state of self-discipline where the need for laying down any formal discipline ceases. For such earnest aspirants, some situations likely to be met with in the ordinary course of life, and some practices—for performing which one need not withdraw from ordinary activities of life necessary for physical and social well-being—are delineated.

Shaivism does not advocate external renunciation and running away from the world—for the cosmos is in Shiva and Shiva is in the cosmos. There is no situation where Shiva is not.

We cognize the external world by five senses—hearing, touch, sight, taste, and smell—which help us to gather knowledge, but which also, often, lead our minds astray. It is for this reason that usually all spiritual disciplines prescribe ways and means to curb and withdraw the senses from the world of manifestation. Shaivism here takes a radically different stand. It attempts to make these very senses and their pleasures stepping stones for the upward path: tasting, smelling, seeing, touching, and hearing. It elevates the pleasures of the senses from the plane of sensuality to that of increasingly refined sensitivity.

This approach appears, no doubt, alluring, but the neophyte must be forewarned. It is perilous too. An undisciplined, unwary, or over-zealous beginner may easily stumble on the very first step and break his limbs. A very cautious approach is needed. A seriousness of purpose to realize the Truth and a whole-hearted devotion to it alone, form the prelude to this search. Plainly speaking, it is not meant for those who are still held by the desire for gross pleasures.

To enable his commentary on this scripture to endure down through the ages, Swami Lakshmanjoo left it in two forms:

(i) a series of videos gracing each verse, which over a few years, John Hughes of the Lakshmanjoo Academy recorded, and

(ii) Swami Lakshmanjoo's textual embodiment of the tapes, The Manual for Self-Realization: 112 Meditations of the Vijñāna Bhairava Tantra (edited by John Hughes).

Both are treasures! In each, Swamiji comments on the scripture while responding to questions from his students. Swamiji emphasizes that the video version transmits his teachings with a higher level of fidelity.