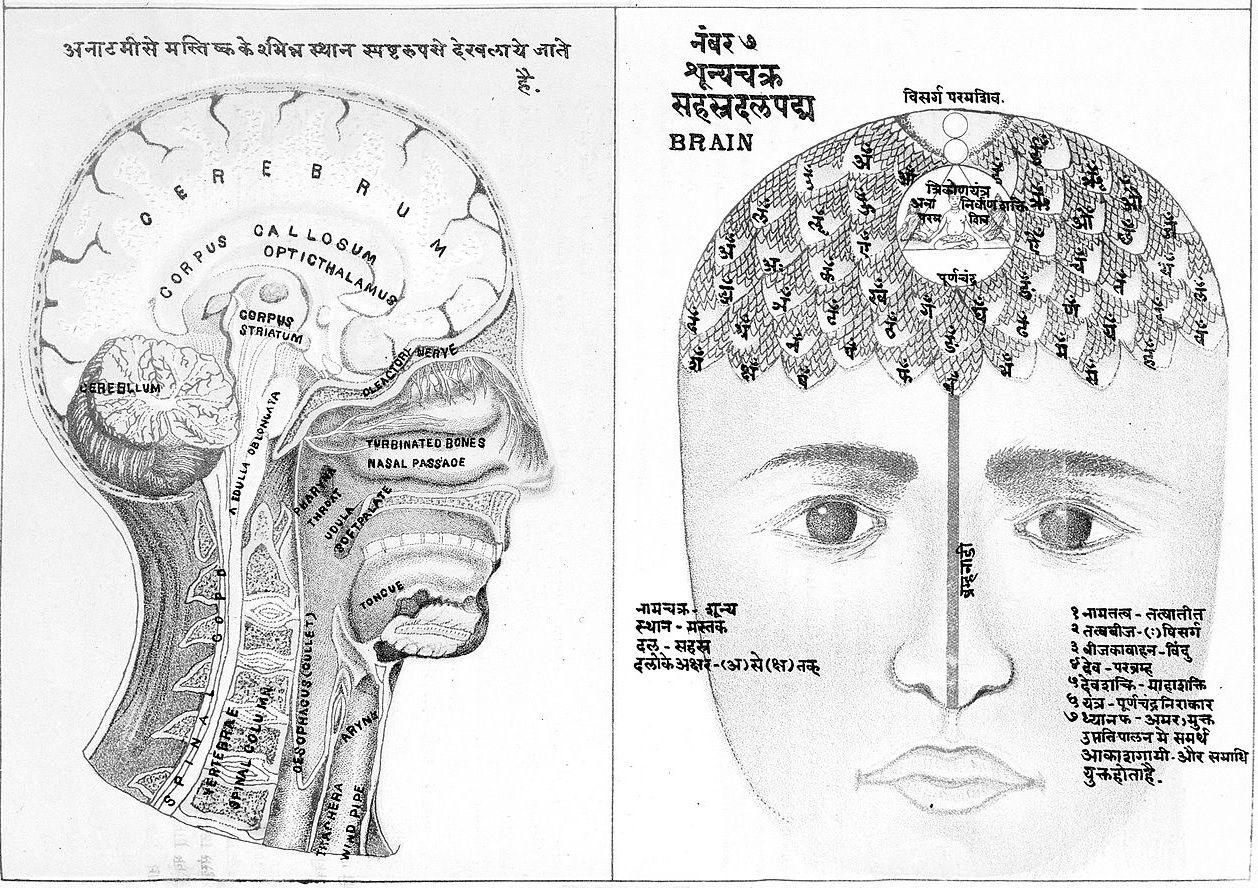

meditation 7

Imagine

the twelve (Sanskrit) vowel sounds . . .

a

ā

i

ī

u

ū

e

ai

o

au

aṃ

aḥ . . .

arise –

each in succession

from its corresponding center

of your body . . .

coccyx

sacrum

navel

heart

throat

palate

middle of eyebrows

forehead

medulla oblongata

cerebellum

cerebrum . . .

first as gross forms

next as vibration

then as light . . .

The mind will thus

merge in light . . .

You are blessed.

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

In his Manual for Self Realization (John Hughes, ed.), Swami Lakshmanjoo refers to the twelve successive points as follows:

Starting with the sound

a

from

from janmārga,

ā

from mūla,

i

from kanda,

ī

from nābhi,

u

from hṛdi,

ū

from kaṇṭha,

e

from tālu,

o

from bhrūmadhya,

ai

from lalāṭa,

au

from

brhamarandhra

aṃ

from śakti,

aḥ

from vyāpinī.

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

To enable his commentary on this scripture to endure down through the ages, Swami Lakshmanjoo left it in two forms:

(i) a series of videos gracing each verse, which over a few years, John Hughes of the Lakshmanjoo Academy recorded, and

(ii) Swami Lakshmanjoo's textual embodiment of the tapes, The Manual for Self-Realization: 112 Meditations of the Vijñāna Bhairava Tantra (edited by John Hughes).

Both are treasures! In each, Swamiji comments on the scripture while responding to questions from his students. Swamiji emphasizes that the video version transmits his teaching with a higher level of fidelity.

In this 1974 – 1975 collaboration, Lakshmanjoo-Muju resorted to Latin. This may have been because of (a) the colonial influence of foreign knowledge on their traditional knowledge and (b) out of courtesy that as someone living in Santa Barbara, California, I may have been more fluent in my mother tongue, English, and Latin, rather than in Sanskrit (which I studied with Nandini Iyer and then Gerald Larson at the University of California, Santa Barbara).

Verse 30

Imagine the twelve vowel sounds ( a, ā, i, ī, u, ū, e, ai, o, au, aṃ, aḥ ) arise in succession from the twelve centres of your body (coccyx, sacrum, navel, heart, throat, palate, middle of eyebrows, forehead, medulla oblongata, cerebellum, cerebrum). First, think of their gross form, then feel them as vibration, and then as light. The mind will thus merge in light. You are blessed.

Ψ

Some analogous hieratic language systems ~

An Introduction to Dhrupad: India's oldest classical music

- Author: Jameela Siddiqi

The word ‘Dhrupad’ is derived from ‘dhruva,’ meaning that which is ‘fixed’ or ‘constant’ and ‘pada', meaning ‘word’ or ‘set-composition’. It is the oldest form of North Indian classical vocal music, with origins lying in the antiquated chanting style of a sacred Sanskrit text known as the Samaveda, dating back to at least 3,000 years ago. A contemplative and meditative form of classical singing, the continuity of dhrupad in the modern age owes its existence to sustained worship rituals that have changed little over the centuries.

This music belonged in Hindu temples and also found a home in the royal courts of both Muslim and Hindu rulers where, and whilst retaining its sacred essence of Vedic chants and mantras, it began to evolve as a sophisticated art form with a complex musical grammar of its own. The best-known performers of this genre, the 'Senior' Dagar Brothers, also took to performing it with two main voices - although the form may not, strictly speaking, be considered a duet.

A central concept in dhrupad singing is the practice of nada yoga – exercises pertaining to an awareness of one’s own inner sounds and vibrations, and of understanding how these sounds and vibrations are the fundamental building blocks of the whole universe. Performers develop an enormous inner resonance of their bodies, so that sound appears to flow freely from the navel to the head, enabling a vast palette of tones and sruti (microtones) to be voiced seemingly effortlessly.

A dhrupad recital is typically divided into two main parts: starting with alap (slow, pulse-free introduction) which is the major part of the performance and which is usually sung using sounds and syllables rather than words (including stylized syllables such as ‘om,’ ‘nam,’ ‘re,’ ‘ri,’ ‘na,’ ‘ta,’ ‘nom,’ ‘tom’). The focus remains solely on the individual notes of the chosen raga (melodic structure) which is explored in depth, aiming to create an atmosphere that engulfs the audience in every shade and nuance of the particular character of that raga.

The alap begins in a low octave, the initial sounds barely audible, gradually rising on the musical scale with a corresponding rise in tempo. By the time this happens, the audience is so enveloped in the music and the tempo is increased in such small fractions that one is barely aware of its change of pace.

This is followed by the second section called dhrupad (the actual song composition), consisting of one or more set verses, always of a devotional nature and usually in Sanskrit or a form of medieval literary Hindi known as Braj Bhasha. The verses are delivered with clearly enunciated words and it is during this section that the singer is joined by a pakhawaj - an ancient, barrel-shaped drum with a deeply resonant sound.

Dhrupad’s popularity was in steady decline since around the beginning of the 18th century and the advent of khayal - another classical vocal form, generally considered to be more accessible. This decline also coincided with a significant shift in Indian musical thinking, whereby older forms, which still retained their associations with devotional rituals, were marginalised in preference to more 'entertaining' music. As a result, dhrupad all but disappeared from performance venues by the mid-20th century, owing to the ending of royal patronage (except for specific gatherings for a very few die-hards).

But in recent years dhrupad has returned with a vengeance – not only in India but also on the international stage – ever since the 1970s, when musicologists such as Alain Daniélou started identifying it as a cultural tradition in danger of total eclipse. A spate of foreign recordings, notably in France and Japan, have led to a tremendous revival in this most ancient form of art music.

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

SACRED LANGUAGE - SACRED TEXT

A hieratic language. The Greek word "hieratic" means "priestly," and was originally used to describe Eqyptian hieroglyphics, a lanquage reserved for spiritual purposes. Hieratic languages such as Hebrew and Sanskrit are seen as "vessels" that protect spiritual concepts. Each letter, each glyphic symbol, contains and transmits"God-force." Each shape, and what it imparts, connects the immanent world to the transcendent world and is a path along which humans can share in that connection. This idea evolves into the idea that simply scanning the letters with the eyes opens the soul to the divine, regardless of comprehension of the meanings.

Sacred Texts. The term "Veda," in its narrow sense, refers to the four primary brahmanic "Samhitas," the Rig Veda, Yajur Veda, Sama Veda, and Atharva Veda. Subsequent writings have been assimilated into the tradition, and "Veda" has become a broader term including a body of literature much larger than the core texts. Similarly, in Judaism, the Sefer Torah [Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy] forms the primary written law, with later works such as the Talmud and Zohar forming a vast body of thought that is sometimes referred to broadly as "Torah."

In both traditions, the primary texts, Torah and Veda, are thought of as entities much greater than simple collections of words. Both are seen as "living bodies" of the Spiritual manifested in the physical world. Both are seen as containing the sum of all knowledge and capable of infinite exploration and permutation. Both are seen as cosmological principles, as essential, primary components of reality itself. Both are closed canons, while still being seen as filled with endless meaning and sustenance. The import of these texts is often seen to transcend the literal meanings of the words, and where human interpretation begins is where endless questions of authority begin. Both traditions have strong systems of interpretation of sacred texts, and encourage difficult questions and expansion of knowledge.

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼