meditation 77

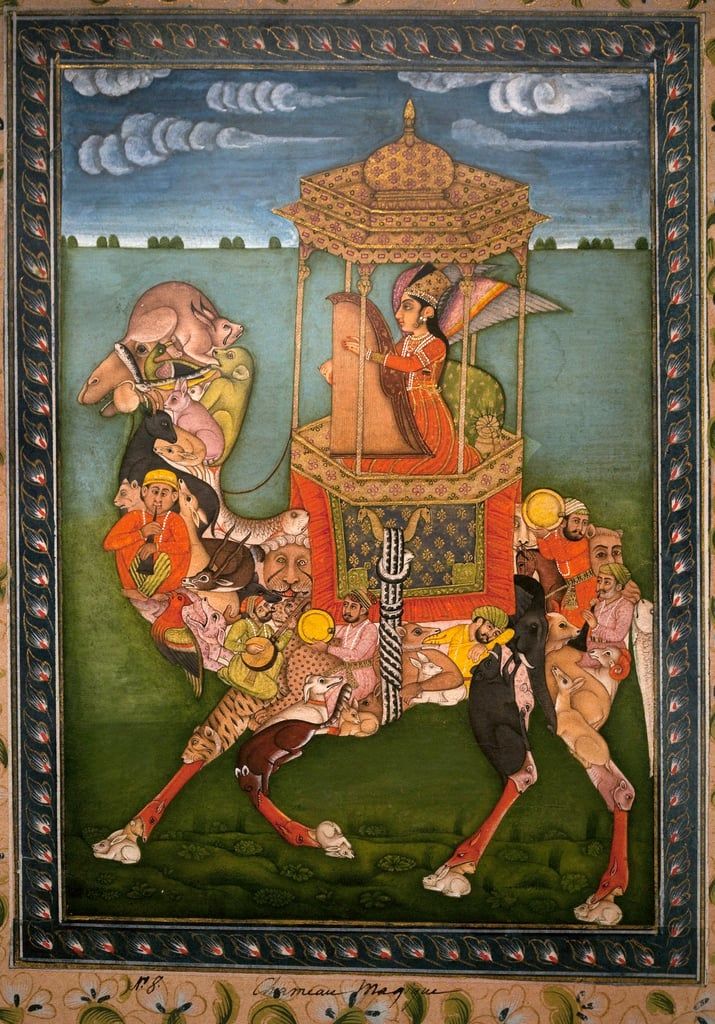

Contemplate that the world

is like a magician's trick

(has no substance of its own

except in the Great Magician)

or is like a moving picture.

Kingdom of Happiness opens.

Notes:

The Kathāsaritsāgara, an enchanting mirage of lore unfolding within fables nested within parables uncurling within allegories blossoming within myths . . . was translated by Somadeva – court poet of King Anantadeva of Kashmir – from an original compilation, now lost, alas, said to have been inked in the tongue of ghosts.

Somadeva did so in order to curry royal favor: by peppering the dreams of the king's beloved, Queen Suryavati, with narrative magic.

Somadeva beginneth with a benediction for his reader –

May the dark neck of Śiva, which the god of love has, so to speak, surrounded with nooses in the form of the alluring looks of Párvatí reclining on his bosom, assign to you prosperity . . .

Somadeva then frames the collection with an announcement.

After worshipping the goddess of Speech, the lamp that illuminates countless objects, I compose this collection, which contains the pith of the Vṛíhat-Kathá (the ghost of the original) . . .

Next to spin a yarn is Shiva, who to fulfill his consort Parvati's wish to hear a tale 'till now untold, launches the collection's first.

Tales later in the Ocean of Story, this very yarn – about magic – washes up . . .

The Magic Wheel

Long ago there was a Bráhman named Yajnasthala . . . dwelling on a royal grant.

He, once upon a time, being poor, went to the forest to bring home wood. There, a piece of wood being cleft with the axe, fell, as chance would have it, upon his leg, and piercing it, entered deep into it. And as the blood flowed from him, he fainted, and he was beheld in that condition by a man who recognized him, and taking him up carried him home. There his distracted wife washed off the blood, and consoling him, placed a plaster upon the wound. And then his wound, though tended day by day, not only did not heal, but formed an ulcer. Then the man, afflicted with his ulcerated wound, poverty-stricken, and at the point of death, was thus advised in secret by a Bráhman friend, who came to him; “A friend of mine, named Yajnadatta, was long very poor, but he gained the aid of a Piśácha by a charm, and so, having obtained wealth, lived in happiness. And he told me that charm, so do you gain, my friend, by means of it, the aid of a Piśácha; he will heal your wound.”

Having said this, he told him the form of words and described to him the ceremony as follows: “Rise up in the last watch of the night, and with disheveled hair and naked, and without rinsing your mouth, take two handfuls of rice as large as you can grasp with your two hands, and muttering the form of words go to a place where four roads meet, and there place the two handfuls of rice, and return in silence without looking behind you. Do so always until that Piśácha appears, and himself says to you, ‘I will put an end to your ailment.’ Then receive his aid gladly, and he will remove your complaint.”

When his friend had said this to him, the Bráhman did as he had been directed. Then the Piśácha, being conciliated, brought heavenly herbs from a lofty peak of the Himálayas and healed his wound. And then he became obstinately persistent, and said to the Bráhman, who was delighted at being healed, “Give me a second wound to cure, but if you will not, I will do you an injury or destroy your body.” When the Bráhman heard that, he was terrified, and immediately said to him to get rid of him—“I will give you another wound within seven days.” Whereupon the Piśácha left him, but the Bráhman felt hopeless about his life. But eventually, he baffled the Piśácha by the help of his daughter, and having gotten over the disease, he lived in happiness.

“Such are Piśáchas, and some young princes are just like them, and, though conciliated, produce misfortune, my friend, but they can be guarded against by counsel. But princesses of good family have never been heard to be such. So you must not expect any injury from associating with me.”

When Somaprabhá heard from the mouth of Kalingasená in due course this sweet, entertaining, and amusing tale, she was delighted. And she said to her—“My house is sixty yojanas distant hence, and the day is passing away; I have remained long, so now I must depart, fair one.”

Then, as the lord of day was slowly sinking to the eastern mountain, she took leave of her friend who was eager for a second interview, and in a moment flew up into the air, exciting the wonder of the spectators, and rapidly returned to her own house.

And, after beholding that wonderful sight, Kalingasená entered into her house with much perplexity, and reflected, “I do not know, indeed, whether my friend is a Siddha female, or an Apsaras, or a Vidyádharí. She is certainly a heavenly female that travels through the upper air. And heavenly females associate with mortal ones led by excessive love. Did not Arundhatí live in friendship with the daughter of king Pṛithu? Did not Pṛithu by means of her friendship bring Surabhi from heaven to earth? And did not he by consuming its milk return to heaven though he had fallen from it? And were not thenceforth perfect cows born upon earth? So I am fortunate; it is by good luck that I have obtained this heavenly creature as a friend; and when she comes to-morrow, I will . . . ”

Thinking such thoughts in her heart, Kalingasená spent that night there, and Somaprabhá spent the night in her own house, being eager to behold her again.

Then in the morning, Somaprabhá took with her a basket, in which she had placed many excellent mechanical dolls of wood with magic properties in order to amuse her friend, and travelling through the air, she came again to Kalingasená.

And when Kalingasená saw her, she was full of tears of joy, and rising up she threw her arms round her neck, and said to her, as she sat by her side—“The dark night of three watches has this time seemed to me to be of a hundred watches without the sight of the full moon of your countenance. So, if you know, my friend, tell me of what kind may have been my union with you in a former birth, of which this present friendship is the result.”

When Somaprabhá heard this, she said to that princess: “Such knowledge I do not possess, for I do not remember my former birth; and hermits are not acquainted with this, but if any know, they are perfectly acquainted with the highest truth, and they are the original founders of the science by which it is attained.”

When she had spoken thus, Kalingasená, being full of curiosity, again asked her in private in a voice tender from love and confidence, “Tell me, friend, of what divine father you have adorned the race by your birth, since you are completely virtuous like a beautifully-rounded pearl. And what, auspicious one, is your name, that is nectar to the ears of the world. What is the object of this basket? And what thing is there in it?”

On hearing this affectionate speech from Kalingasená, Somaprabhá began to tell the whole story in due course.

“There is a mighty Asura of the name of Maya, famous in the three worlds. And he, abandoning the condition of an Asura, fled to Śiva as his protector. And Śiva having promised him security, he built the palace of Indra. But the Daityas were angry with him, affirming that he had become a partizan of the gods. Through fear of them he made in the Vindhya mountains a wonderful magic subterranean palace, which the Asuras could not reach. My sister and I are the two daughters of that Maya. My elder sister, named Svayamprabhá, follows a vow of virginity, and lives as a maiden in my father’s house. But I, the younger daughter, named Somaprabhá, have been bestowed in marriage on a son of Kuvera, named Naḍakúvara, and my father has taught me innumerable magic artifices, and as for this basket, I have brought it here to please you.”

Having said this, Somaprabhá opened the basket and shewed to her some interesting mechanical dolls constructed by her magic, made of wood. One of them, on a pin in it being touched, flew through the air at her orders and fetched a garland of flowers and quickly returned. Another, in the same way, brought water at will. Still another, danced, and another then conversed.

With such very wonderful contrivances, Somaprabhá amused Kalingasená for some time, and then she put that magic basket in a place of security, and taking leave of her regretful friend, she went, being obedient to her husband, through the air to her own palace.

But Kalingasená was so delighted that the sight of these wonders took away her appetite, and she remained averse to all food. And when her mother perceived that, she feared she was ill. However a physician named Ánanda, having examined the child, told her mother that there was nothing the matter with her. He said, “She has lost her appetite through delight at something, not from disease; for her countenance, which appears to be laughing, with eyes wide open, indicates this.”

When she heard this report from the physician, the girl’s mother asked her the real cause of her joy; and the girl told her. Then her mother believed that she was delighted with the society of an eligible friend, and congratulated her, and made her take her proper food.

Then, the next day, Somaprabhá arrived, and having found out what had taken place, she proceeded to say to Kalingasená in secret, “I told my husband, who possesses supernatural knowledge, that I had formed a friendship with you, and obtained from him, when he knew the facts, permission to visit you every day. So you must now obtain permission from your parents, in order that you may amuse yourself with me at will without fear.”

When Somaprabhá had said this, Kalingasená took her by the hand, and immediately went to her father and mother, and there introduced her friend to her father, king Kalingadatta, proclaiming her friend's descent and name, and in the same way she introduced friend to her mother, Tárádattá, and they, on beholding Somaprabhá, received her politely in accordance with their daughter’s account of her.

And both those two, pleased with her appearance, hospitably received that beautiful wife of the distinguished Asura out of love for their daughter, and said to her—“Dear girl, we entrust this Kalingasená to your care, so amuse yourselves together as much as you please.”

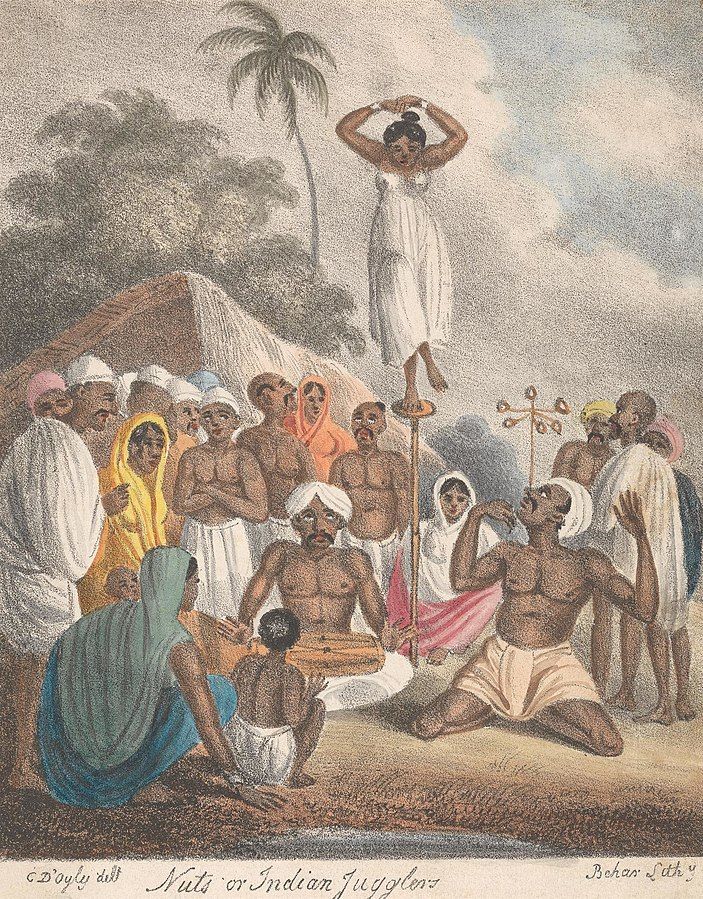

And Kalingasená and Somaprabhá, having gladly welcomed this speech of theirs, went out together. And they went, in order to amuse themselves, to a temple of Buddha built by the king. And they took there that basket of magic toys. Then Somaprabhá took a magic Yaksha, and sent it on a commission from herself to bring the requisites for the worship of Buddha. That Yaksha went a long distance through the sky, and brought a multitude of pearls, beautiful gems, and golden lotuses. Having performed worship with these, Somaprabhá exhibiting all kinds of wonders, displayed the various Buddhas with their abodes.

When the king Kalingadatta heard of that, he came with the queen and beheld it, and then asked Somaprabhá about the magic performance. Then Somaprabhá said, “King, these contrivances of magic machines, and so on, were created in various ways by my father in old time. And even as this vast machine, called the world, consists of five elements, so do all these machines: I will describe them one by one.

"That machine, in which earth predominates, shuts doors and things of the kind. Not even Indra would be able to open what had been shut with it.

"The shapes produced by the water-machine appear to be alive.

"But the machine in which fire predominates, pours forth flames.

"And the wind-machine performs actions, such as going and coming.

"And the machine produced from ether utters distinct language.

"All these I obtained from my father, but the wheel-machine, which guards the water of immortality, my father knows and no one else.”

While she was saying this, there arose the sound of conchs being blown in the middle of the day, that seemed to confirm her words. Then she entreated the king to give her the food that suited her, and taking Kalingasená as a companion, by permission of the king, she set out through the air for her father’s house in a magic chariot, to return to her elder sister.

And quickly reaching that palace, which was situated in the Vindhya mountains, she conducted her to her sister Svayamprabhá.

There Kalingasená saw that Svayamprabhá with her head encircled with matted locks, with a long rosary, a nun clothed in a white garment, smiling like Párvatí, in whom love, the highest joy of earth, had undertaken a severe vow of mortification. And Svayamprabhá, when the princess, introduced by Somaprabhá, kneeled before her, received her hospitably and entertained her with a meal of fruits. And Somaprabhá said to the princess: ‘My friend, by eating these fruits, you will escape old age which otherwise would destroy this beauty, as the nipping cold does the lotus: and it was with this object that I brought you here out of affection.’ Then that Kalingasená ate those fruits, and immediately her limbs seemed to be bathed in the water of life. And roaming about there to amuse herself, she saw the garden of the city, with tanks filled with golden lotuses, and trees bearing fruit as sweet as nectar: the garden was full of birds of golden and variegated plumage, and seemed to have pillars of bright gems; it conveyed the idea of walls where there was no partition, and where there were partitions, of unobstructed space. Where there was water, it presented the appearance of dry land, and where there was dry land, it bore the semblance of water. It resembled another and a wonderful world, created by the delusive power of the Asura Maya. It had been entered formerly by the monkeys searching for Sítá, which, after a long time, were allowed to come out by the favour of Svayamprabhá.

So Svayamprabhá bade her adieu, after she had been astonished with a full sight of her wonderful city, and had obtained immunity from old age; and Somaprabhá making Kalingasená ascend the chariot again, took her through the air to her own palace in Takshaśilá. There Kalingasená told the whole story faithfully to her parents, and they were exceedingly pleased.

And while those two friends spent their days in this way, Somaprabhá once upon a time said to Kalingasená: “As long as you are not married, I can continue to be your friend, but after your marriage, how could I enter the house of your husband? For a friend’s husband ought never to be seen or recognised.

Source: The Kathá Sarit Ságara or Ocean of the Streams of Story

Translated from the original Sanskrit

by

C. H. Tawney, M. A.

Calcutta:

Printed by J. W. Thomas, at the Baptist Mission Press, 1880

Please refer to The Manual for Self Realizationm wherein Swami Lakshmanjoo comments at length on the Great Magician and the magic of causing what I depict here as the Magic Camel of Existence to appear as if composed of differentiated beings, although it is one undifferentiated whole.

This is Verse 102

Swamiji and Panditji's translation reads as follows:

Verse 102

Contemplate that the world is like a magician's trick (i.e. has no substance of its own except in the Great Magician) or is like a moving picture. Kingdom of Happiness opens.