meditation 78

Engross

not

thy mind

in pleasure

or

in pain

but in the force

moving

amid

both –

whose Residue

is

Reality.

Notes:

This verse is about the One among the many.

Swami Lakshmanjoo and Pandit Dina Nath Muju's original reads as follows:

Verse 103

Engross not thy mind in pleasure or pain, but witness the force moving in both. The Residue is Reality.

Surprisingly, Swamiji and Panditji's (1974 – 1975) translation of Verse 103 does not mention the important concept of in the middle (madhye), as does Jaideva Singh's 1979 translation (The Yoga of Delight, Wonder, and Astonishment) and also Lakshmanjoo and Hughes' The Manual for Self Realization.

All three arose within Swamiji's sphere of influence, so I recommend comparing each with each.

Though Swamiji and Panditji do not mention madhye in their 1974 – 1975 translation, perhaps they allude to it indirectly by their use of the English word moving [amid] both.

What moves amid duḥkha (pain, suffering, unease) and sukha (joy, happiness, pleasure)?

Let us first consider things non-moving, a species of naught.

Influenced by Buddism, the Vijñāna Bhairava is replete with oughts and naughts: the latter both announced and implied.

Of naughts, the scripture offers up a gaggle of ungraspable vacuities, voids, aporiae, holes, hollows, spaces, and kindred nils and aughts.

This ungraspability is strategic.

It publs the rug out from under mind.

For instance, the naughts between breaths, thoughts, neithers and nors; within the Central Channel, within the voids of circles adorning peacock tail feathers, within the void of the pranava mantra, within the letters of the alphabet; within the circumambient space surrounding the body, within the space within the heart, within the space remaining after the dissolution of the body, the space imagined within the skin of the vacuous body, within the vacuities within jars, the vacuities surrounding one when atop a mountain, the hollows of holes which are wells . . .

The naught of importance here, though, is the one inhabiting the traditional chariot (ratha), particularly the wheels and axle – and even more important, the hollow nave: the circular spatial void within which the wheel's axle fits, radiating the many spokes, imagistically akin to the spread of a peacock's 150 tail feathers.

This vacuity, as we shall see, implies not only chariot but also echoes all the other naughts in the scripture – and in all of existence.

Of oughts, the scripture suggests we contemplate, meditate on, imagine, consider, become aware of, observe, realize, or ponder, various naughts . . .

In this verse, Bhairavi, the God's better half, is asked to engross her mind neither in pleasure nor in pain but in the force moving amid duḥkha (pain, suffering, unease) and sukha (joy, happiness, pleasure, bliss).

First, linguistically: what moves within the words duḥkha and sukha?

What moves within pleasure and pain is the wheel of the ever-moving chariot of the five senses. This "wheel" gives rise to both. The wheel and chariot are implied by the noun kha, which can mean axle hole or simply hole.

So what moves within this chariot wheel of the five senses is kha – an unmoving, Prime Mover, the empty whole which is the womb of both pleasure and pain.

In other contexts, kha can mean void, empty space (of the heart), suṣumṇā-nāḍī, cranial vault, cavity . . .

In his translation of the Bhagavad Gita, Winthorp Sargeant:

"Su" and "dus" are prefixes indicating good or bad. The word kha," in later Sanskrit meaning "sky," "ether," or "space," was originally the word for "hole," particularly an axle hole of one of the Aryan's vehicles. Thus . . . "sukha" (a BV cpd.) meant, originally, . . . "having a good axle hole," while "duḥkha" meant "having a poor axle hole," leading to discomfort.

Predictably, contemporary Buddhist teacher Joseph Goldstein, in Mindfulness: A Practical Guide to Awakening, Sounds True, Kindle Edition, (2013), leans decidedly toward the kha-as-empty school:

The word dukkha is made up of the prefix du and the root kha. Du means "bad" or "difficult". Kha means "empty". "Empty", here, refers to several things—some specific, others more general. One of the specific meanings refers to the empty axle hole of a wheel. If the axle fits badly into the center hole, we get a very bumpy ride. This is a good analogy for our ride through samsara.

Lexicographer Monier Williams, who wanted to convert all of the subcontinent to Christianity, had his own ideas on the etymology of the word.

The Sanskrit word for chariot is ratha (chariot).

Ψ

I was struck by the way Swamiji and Panditji's (1974 – 1975) translation of this verse leads with a somewhat archaic but bold and emphatic rhetorical flourish: the way they employ the word not to directly negate the verb engross . . .

Engross not thy mind , , ,

. . . thus echoing a line in Shakespeare's Hamlet: the titular character given — when faced with contemplating opposites ("to be or not to be . . . ") — to the force of aporiae.

"I pray thee, stay with us. Go not to Wittenberg." —Gertrude, in Shakesphere's Hamlet

I assume Panditji, as a pandit steeped in English, had long been exposed to the rhetorical devices of apophatic philosophy, and not only in the scripture under consideration, but in other sources which — laying bare their own in-betweens, their own middle grounds — run rich in veins of negations and naughts: neither-nors, neti netis, nots.

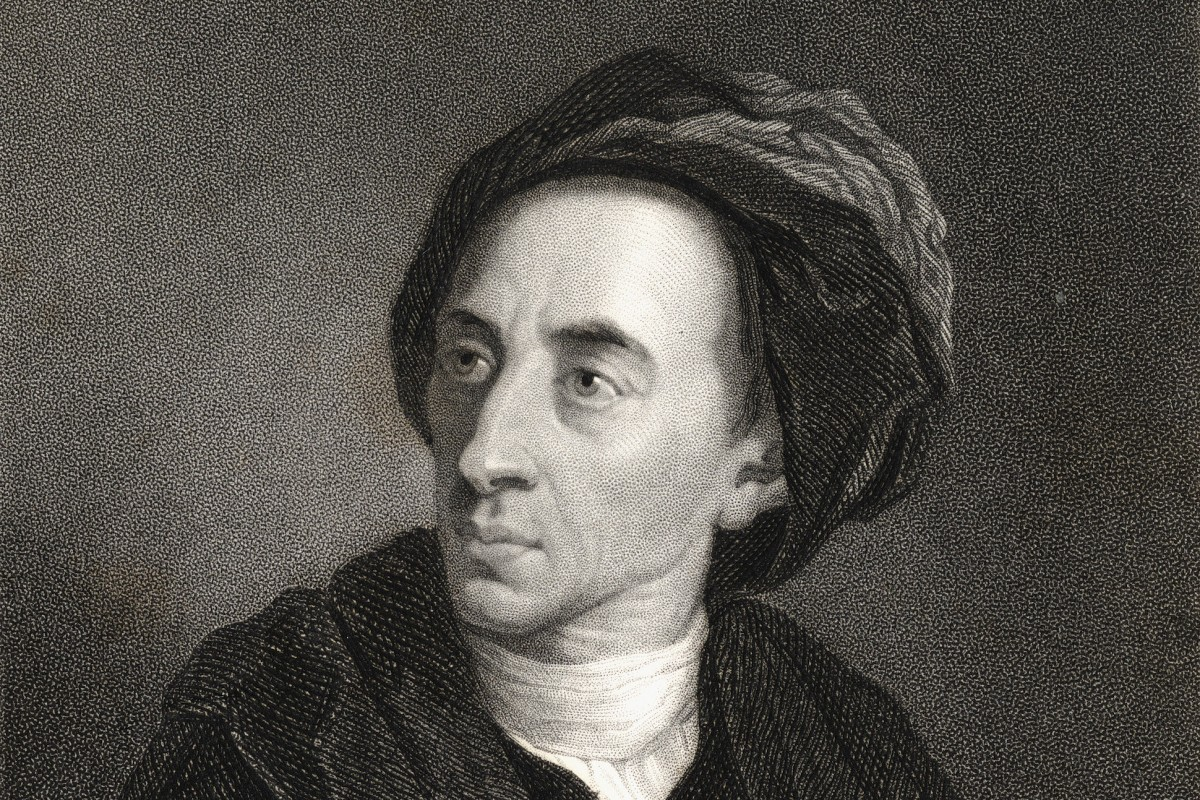

Panditji had a voluminous library. I would not be surprised to learn he had been a fan of John Milton's Essay on Man, Epistle I.

In Milton's somewhat neo-Platonic jest, would Panditji have recognized the allure of the in-between-opposites similar to those of the Vijñāna Bhairava?

Know then thyself, presume not God to scan;

The proper study of Mankind is Man.

Plac'd on this isthmus of a middle state,

A being darkly wise, and rudely great:

With too much knowledge for the Sceptic side,

With too much weakness for the Stoic's pride,

He hangs between; in doubt to act, or rest,

In doubt to deem himself a God, or Beast;

In doubt his Mind or Body to prefer,

Born but to die, and reas'ning but to err;

Alike in ignorance, his reason such,

Whether he thinks too little, or too much:

Chaos of Thought and Passion, all confus'd;

Still by himself, abus'd, or disabus'd;

Created half to rise, and half to fall;

Great lord of all things, yet a prey to all;

Sole judge of Truth, in endless Error hurl'd:

The glory, jest, and riddle of the world!

Go, wond'rous creature! mount where Science guides,

Go, measure earth, weigh air, and state the tides;

Instruct the planets in what orbs to run,

Correct old Time, and regulate the Sun;

Go, soar with Plato to th' empyreal sphere,

To the first good, first perfect, and first fair;

Or tread the mazy round his follow'rs trod,

And quitting sense call imitating God;

As Eastern priests in giddy circles run,

And turn their heads to imitate the Sun.

Go, teach Eternal Wisdom how to rule—

Then drop into thyself, and be a fool![10]

— Epistle II, lines 1-30

Neither/nor functions in both apophatic and aporetic discourse.

To impel mental impasse.

A Dual Negation whose Residue

Resides in the Middle:

In Reality.

For some, the Middle comes into play between breaths, thoughts, and in the Central Channel.

For some, it is simply Shoreless Awareness.

For others, It is the Center of All.

Some variations on the One Being the Many

Many monistic philosophies seek to represent how One appears as many.

In Kashmir, both Abhinavagupta and Utpaladeva were influenced by Bhartṛhari, who taught (i) that the One is the many; (ii) that the powers identical to Itself are collected in the Brahman of the nature of Word, without contradicting its Oneness; and (iii) that Speech, though One, appears in manifold forms.

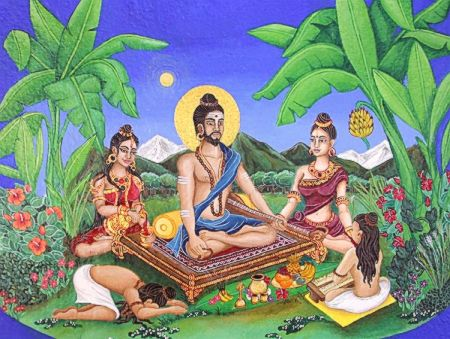

In the domain of Shiva, three other representations, each beginning with the word eka (one), illustrate variations on a theme:

(i) Eka Pada Bhairava

(ii) Aja Eka Pada (Ajaikapada)

(ii) Ekashara

First, Eka Pada Bhairava (from Wikipedia)

Ekapada refers to a one-footed aspect of the Hindu god Shiva. This aspect is primarily found in South India and Orissa, but also occasionally in Rajasthan and Nepal. The Ekapada is primarily represented in three iconographical forms. In the Ekapada-murti ("one-footed icon") form, he is depicted as one-legged and four-armed. In the Ekapada-Trimurti ("one-footed Trinity") form, he is henotheistically depicted with the torsos of the deities Vishnu and Brahma, which together with Shiva form the Hindu Trinity (Trimurti) emanating from his sides, waist upwards and with one leg; however, sometimes, besides the central one leg of Shiva, two smaller legs of Vishnu and Brahma emerge from the sides. While some scriptures also call the latter configuration Ekapada-Trimurti, some refer it to as Tripada-Trimurti ("three-footed Trinity").

In Orissa, where Ekapada is considered an aspect of Bhairava—the fearsome aspect of Shiva—the iconography of Ekapada-murti becomes more fierce, with motifs of blood sacrifice. This aspect is called Ekapada Bhairava ("one-footed Bhairava" or "the one-footed fierce one").

Second, Aja Eka Pada (Ajaikapada)

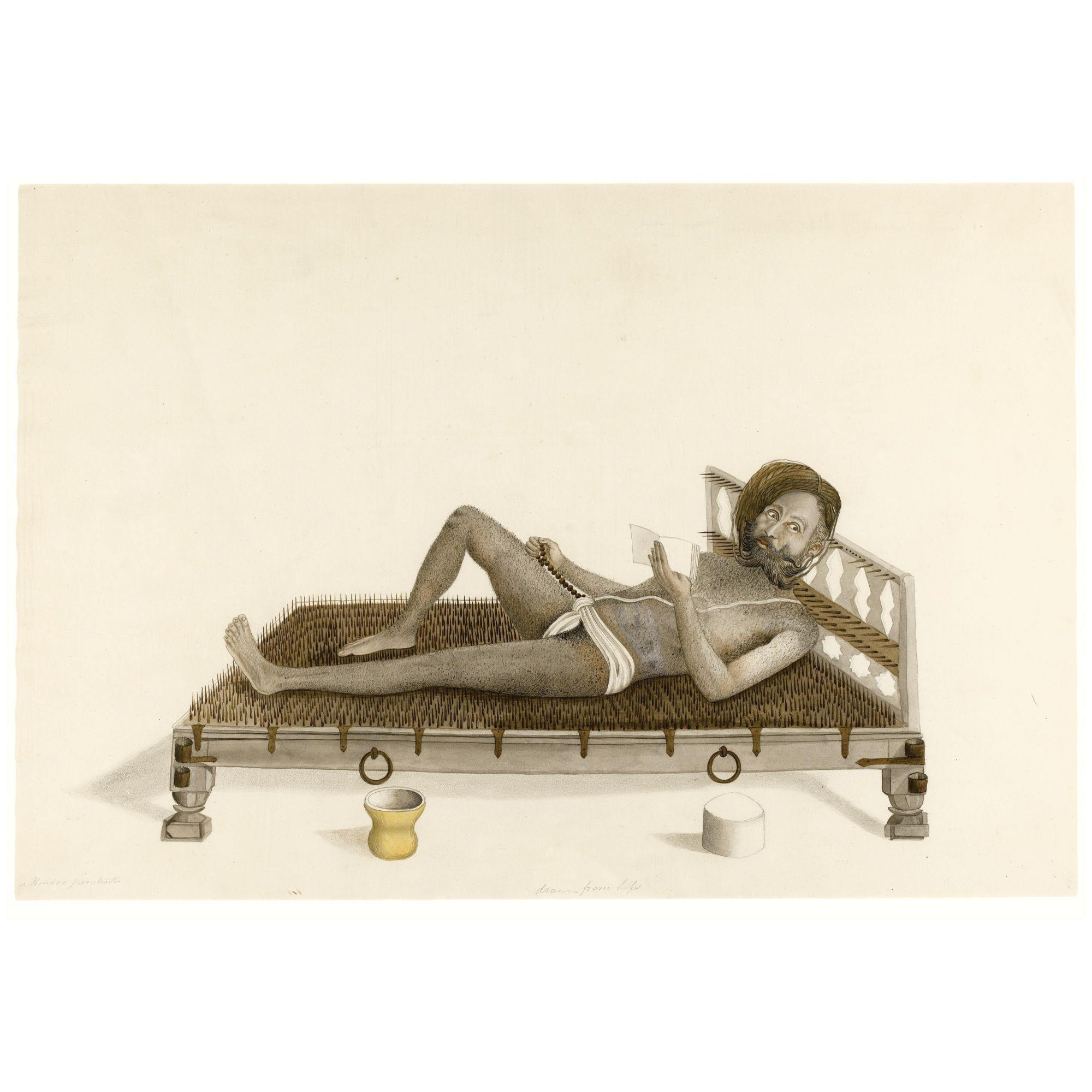

The Ekapada form of Shiva originated from the Vedic deity Aja Ekapada or Ajaikapada, a name that Ekapada Bhairava still inherits. Ekapada represents the Axis Mundi (cosmic pillar of the universe) and portrays Shiva as the Supreme Lord, from whom Vishnu and Brahma originate. Ekapada is often accompanied by ascetic attendants, whose presence emphasizes his connection to severe penance.

Ψ

The supporter of the sky, streams, and oceans, and associated with the thundering floods. Aja-Eka-Pada was described as a kind of Agni, Apam Napat, the raging fire in the ocean-waters.

Aja-Eka-Pada was, of course, associated with Rudra and then Shiva.

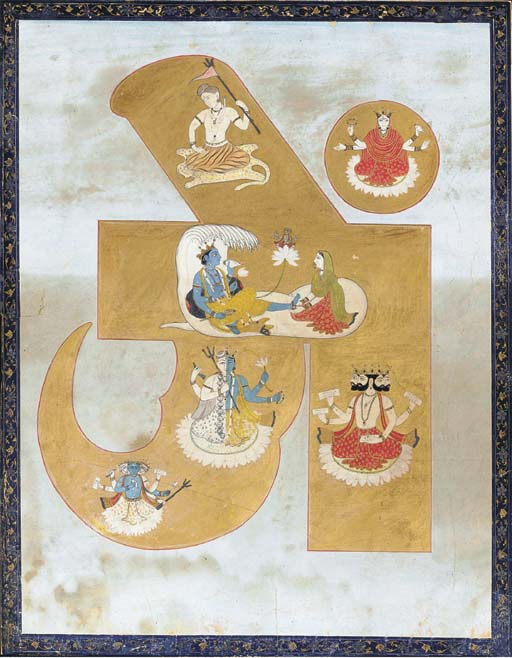

Third ~ Ekashara (Source: Wikipedia)

The Ekakshara Upanishad (Sanskrit: एकाक्षर उपनिषत्; IAST: Ekākshara Upaniṣat), also titled Ekaksharopanishad (Sanskrit: एकाक्षरोपनिषत्), is a minor Upanishadic text of Hinduism written in Sanskrit language. It is attached to the Krishna Yajurveda, and is a Samanya (general) Upanishad.[2]

The Upanishad discusses Om (Pranava) as the Ultimate Reality Brahman, equating it to the imperishable truth and sound, the source of the universe, the Uma, the Shiva, the Narayana, the Atman (soul) that resides in one's heart.[3][4][5]

The one immortal syllable (Ekakshara), is described in the text as the Hiranyagarbha (the golden fetus, the sun, Brahma), the manifested universe, as well as the guardian of the universe.[4][6]

History

Ekakshara, literally "the one syllable", refers to Om of Hinduism.[1][7] It refers to the primordial sound, the seed, the source of the empirically observed universe, representing the totality of manifested changing cosmos and the unchanging supreme reality Brahman.[1]

The term Upanishad means it is knowledge or "hidden doctrine" text that belongs to the corpus of Vedanta literature collection presenting the philosophical concepts of Hinduism and considered the highest purpose of its scripture, the Vedas.[8]

Manuscripts of this text are also found titled as Ekaksaropanisad.[4][9] In the Telugu language anthology of 108 Upanishads of the Muktika canon, narrated by Rama to Hanuman, it is listed at number 69.[10]

Contents

This Upanishad, presented in 13 verses, is dedicated to Ekaksara.[4] The Ekaksara is a compound of Ek (one) and Aksara (syllable), or the imperishable syllable in Hindu tradition, the Om.[11] The text follows the Sabda-brahman tradition. One of the earliest mentions of Ekaksara as OM, the cosmic sound, it being Brahman and the source of the universe, is found in verses 6.22-6.23 of the Maitri Upanishad, as well as in the Brahmana layer of the Vedic literature.[12]

The imperishable

The text opens declaring Om the Ekakshara as the one imperishable, it is Sushumna (kindest core), it is all that is here, that which is unchanging firm, the primordial source of all, the one that created water wherein life arose, the protector, the only one.[13][14] The verses 2 and 3 of the Upanishad state that the Ekakshara is the ancient unborn, and the first born therefrom, the immanent truth, the transcendental reality, the one who sacrifices all the time, the fire, the always omnipresent, the principle behind life, the manifested world, the womb, the child from the womb, the cause, and the cause of the causes.[13][14]

The text asserts that it is the Ekakshara that created the Surya (sun), the Hiranyagarbha the golden womb of everything, the manifested cosmos, the Kumara, the Arishtanemi, the source of the thunderbolt, the leader of all beings.[15] It is the Kama (love) in all beings, states the Upanishad, it is the Soma, the Svaha, the Svadha, the Rudra without suffering in the heart of all beings.[13][14]

The eternal

Ekakshara is that which is all pervading, the divine, the bliss of aloneness, the one eternal support, the cleanser, the past of everything, the present of everything and the future of everything, the imperishable syllable, asserts the text. Verse 7 states that the Rigvedic hymns, the songs of Samaveda, the formulas of Yajur, originate in this cosmic syllable, it is all knowledge, it is all sacrifice, it is the purpose of all striving.[16][14] It dispels the darkness, it is the light in which the Devas dwell, it is all knowledge, it is that what is the fulcrum of all beings, it is pure truth, it is that which isn't born, it is sum total of everything, it is what the Vedas sing, it is the Brahman that the knowers know.[14]

The one in every being

Om, the Ekakshara, is every man, every woman, every boy, every girl, states the Upanishad.[17][18] It is the king Varuna, the Mitra, Garuda, Chandrama (moon), Indra, Rudra, Tvastr, Vishnu, Savitr, the earth, the atmosphere, the land, the water, the womb of all that is born, that which envelops the world, and the self-born states the text. It is the protector Vishnu, who guides away from what is wrong. It, states the Upanishad in verse 13, is wisdom, is the aim of those who seek wisdom, that which is in the heart of every being, the eternal dwelling innermost self, the golden truth.[19][14] Thus ends the Upanishad.[20]

Ψ

Herein, within the realm of this primordial, unborn vibration, divine perception dawns.

Herein the mechanics of creation unfold.

Herein the One creates the many.

Om is where the art is.

Ψ

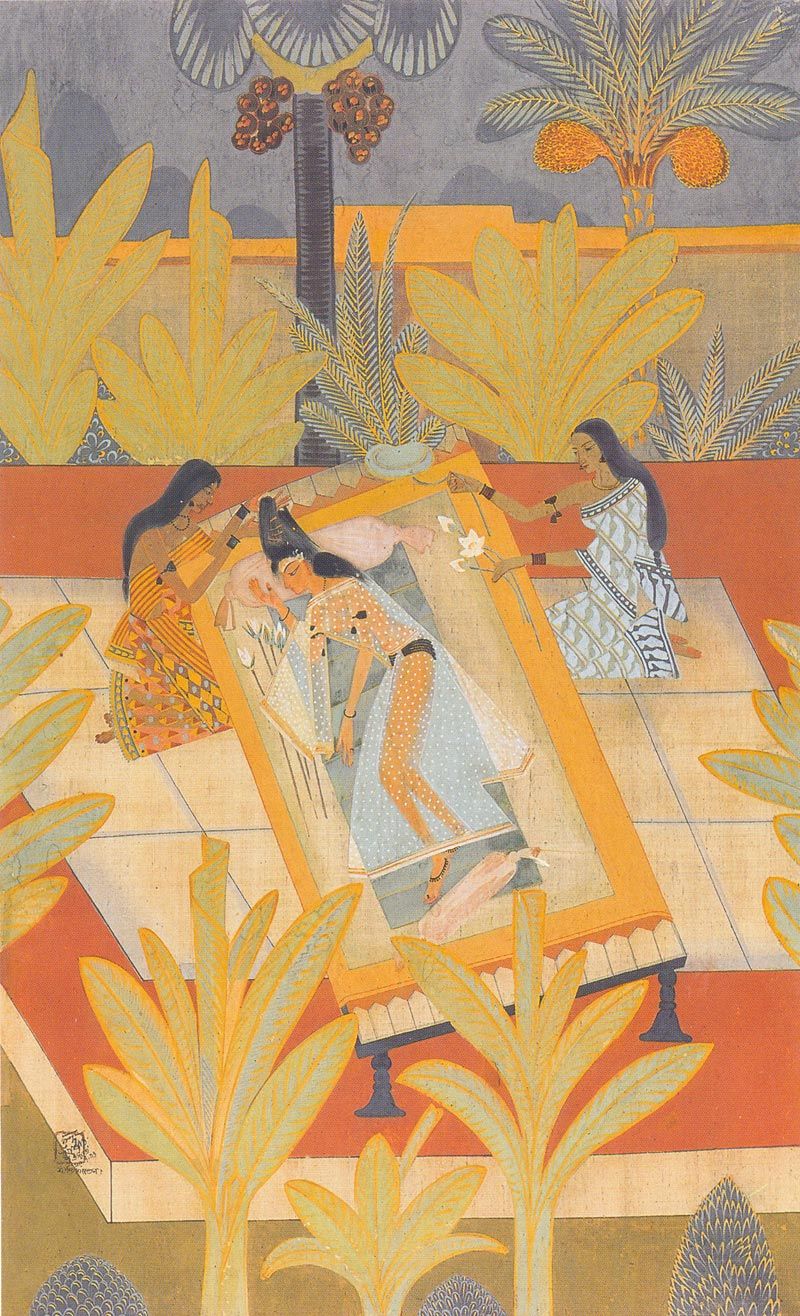

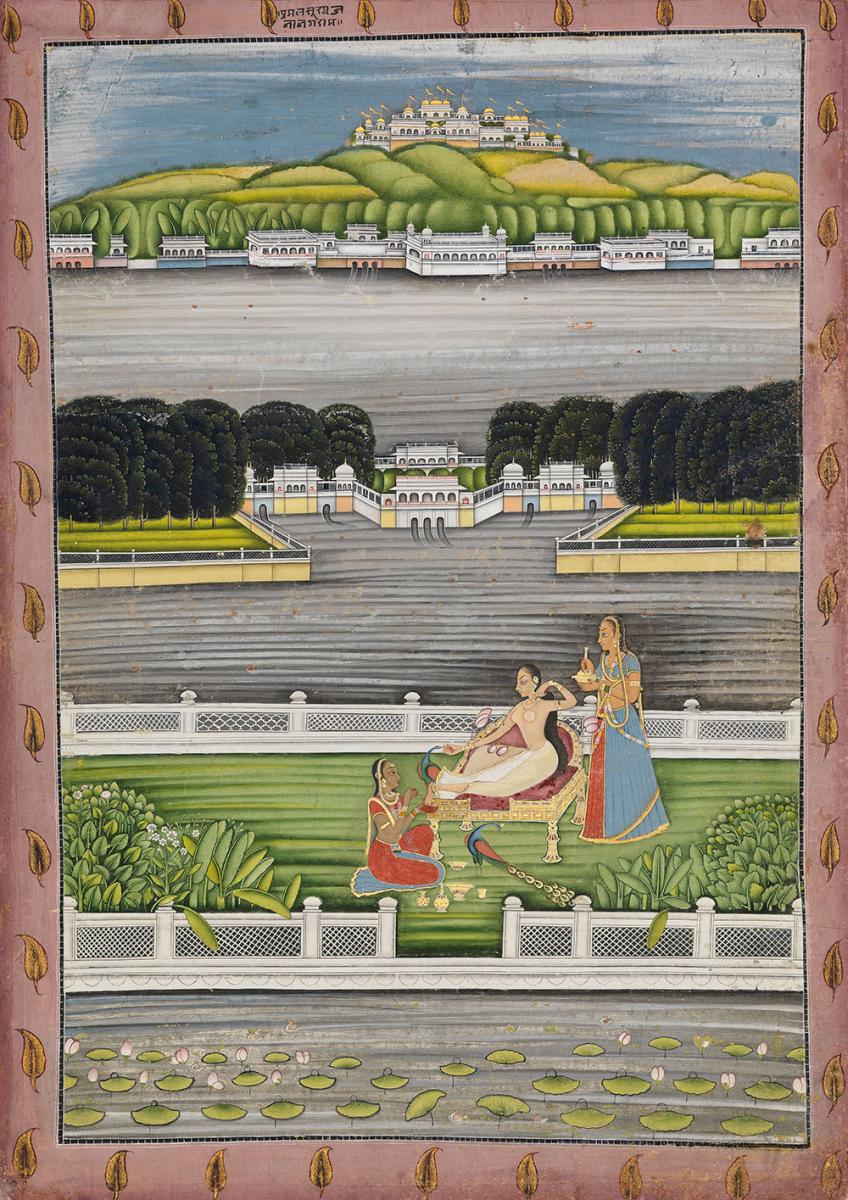

In addition to the Middle's philosophical analogs and spiritual reality – there are, in a Glass-Bead-Game kind of way – also aesthetic counterparts.

For instance, consider the One rasa ("taste") of peace we find in the harmonic "middle" amid Dhruvpad's eternal contemplation of the tonic. Note also the One tala, the rhythmic cycle, the rhythmic Center of this offering, amidst its varied expressions:

[Dhrupad is a style of music influenced by the incantatory resonance of Sama Veda. The Seers of the Vedas are often referred to as Vipras: the word vipra being a cognate of the English words vibration and vibe. The Vipra "may have denoted a moved, inspired, ecstatic, and enthusiastic seer as a bearer or pronouncer of the emotional and vibrating, metrical sacred words (Jan Gonda, Vision of the Vedic Poets, p. n 45).

The Vipra, then, was one who experienced the vibration, energy, and rapture of religious and aesthetic cognition. The word dhrupad is derived from the words dhruva (Pole Star) and the word pada (poetry). All Indian classical music orbits tonally, in unwavering waves of contemplation, around the bright, unmoving "Pole Star" of the tonic. Devotional rather than merely entertaining, drupad flows from the heart's utter core. Scholars trace the dhrupad imagery back to Ajaikapada (Aja Eka Pada), of the Vedas.]

Clap along to One rhythmic center among its many konnokal variations, below . . .

Or attempt clapping all the way through to the One unsquare beat slithering amid these trickster-like waves . . .