meditation 97

Purity

is a relative construct.

In the Absolute

such a construct

is impurity

(because dualistic).

That State [of the Absolute]

is beyond purity

and impurity alike.

Non-formation

of constructs

makes one Divine.

Note:

This is verse 123 of the Vijñāna Bhairava.

Swami Lakshmanjoo and Pandit Dina Nath Muju's 1974–1975 original follows:

What is purity is a relative concept. Such a concept is impurity in the Absolute (as it implies duality). That state is beyond purity and impurity alike. Non-formation of concepts makes you Divine.

The concern with conceptualizing purity here arises as a Shaivite response to India’s Brahmanical culture.

There are certain laws of interaction between members of various castes.

Social anthropologist McKim Marriott wrote that when he performed his field work on the caste system—he found that enculturated village Brahmins in Indian villages do not behold a world made up of individuals, but of what he calls dividuals.

In other words, some Brahmins may not envision themselves as whole, indivisible, and inviolable—but divisible.

For instance, the number 100 can be fluidly and infinitesimally eroded away by means of its divisibility by all other numbers. Similarly the lifestreams of Brahmins, and everyone else, can be believed to be divisible: diluted, influenced, polluted, or purified by various other streams of life flowing through and around them.

A similar concept of fluidity is found in India's traditional Ayurvedic medicine. It posits that if you take a constitutionally fiery fellow in August and feed him chilies and other heating foods, he might prove to be prone to certain fiery imbalances: anger, inflammation, and so on.

The humoral approach of Ayurveda sees human, horse, and tree physiologies streaming with spacey, airy, fiery, watery, and earthy "elements." Each person’s stream of life, then, is partly made up of such elements.

During winter months, the environment is predominantly cool. The air and space elements predominate. The pulse and speech may become erratic, the heart anxious, the pulse irregular, and the mind scattered. Nervous-system-related imbalances may bubble up.

Eating warming, heavier foods; maintaining a regular routine; and getting to bed before ten every night will help counterbalance the season's influences.

So, the “individual” human physiology may become imbalanced by its day-to-day immersion in seasonal changes. Exposure to an abundance of one element may lead to predictable imbalances.

Similarly, according to Marriot, village Brahmins are ultimately concerned with streaming purity. They envision themselves as the possessors of their social system's greatest purity, which reigns as a highly esteemed quality of their embodiment.

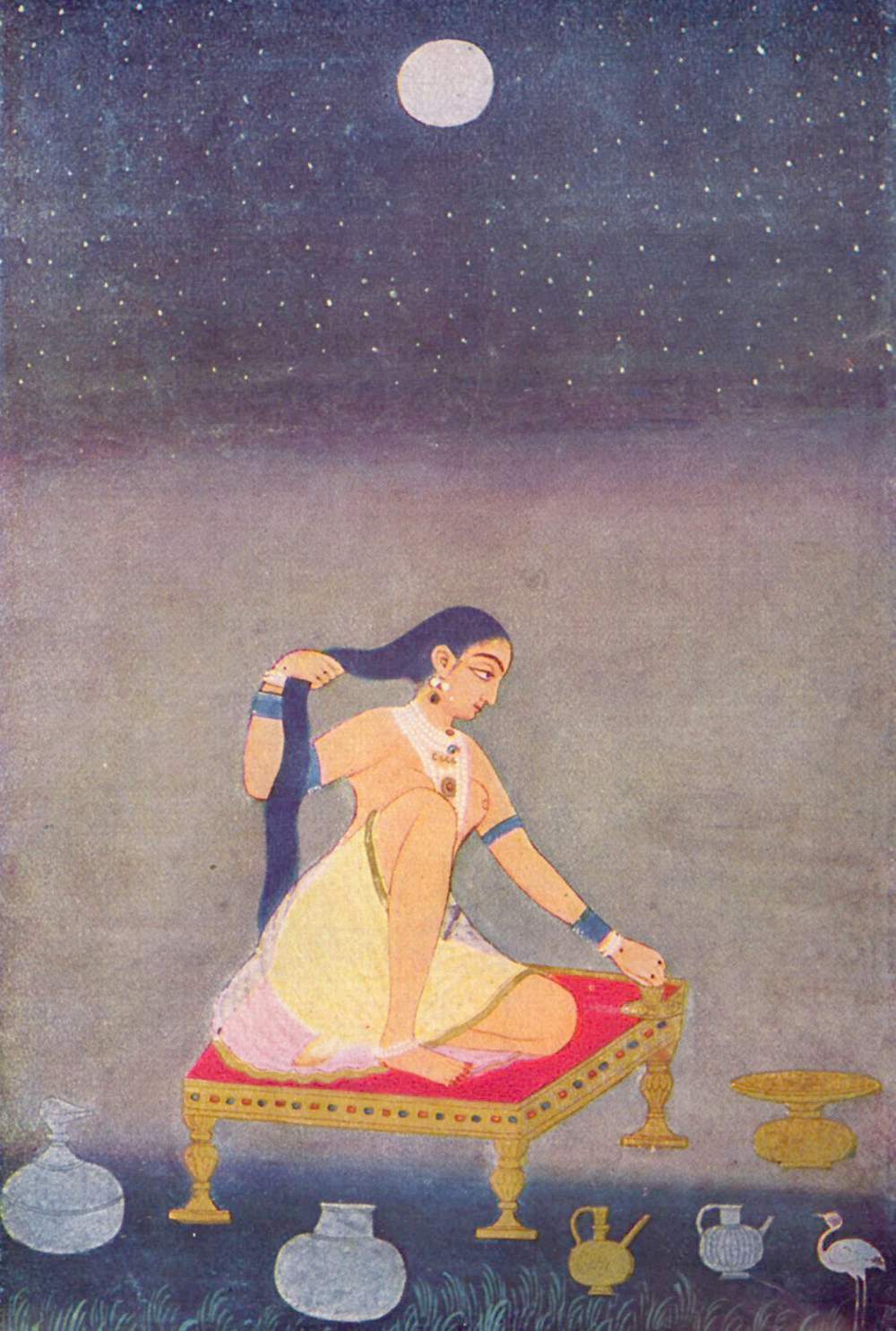

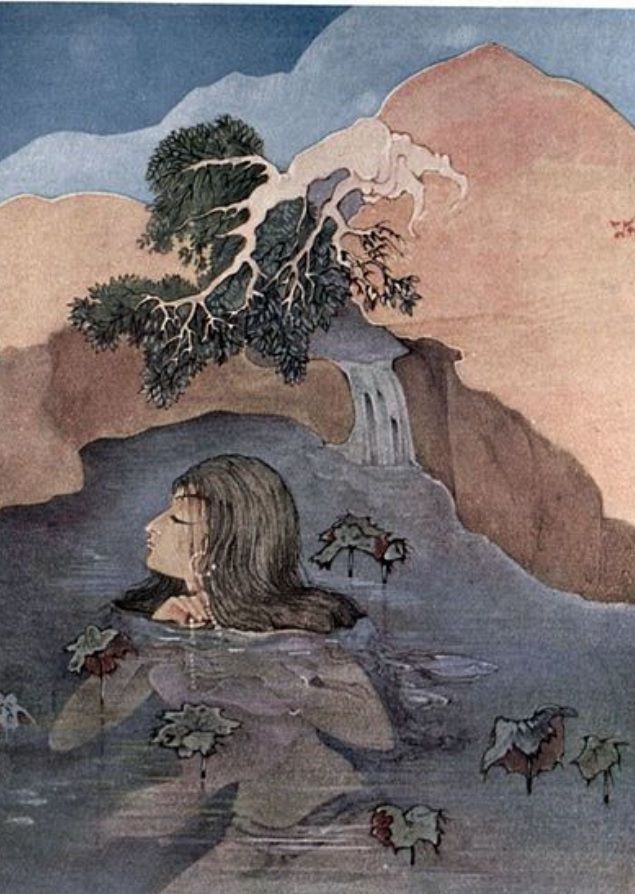

If the stream of their divisible selves were water, then orthodox Brahmins could easily envision themselves as something like water flowing from a pristine spring, cascading effortlessly down a snow-crowned mountain.

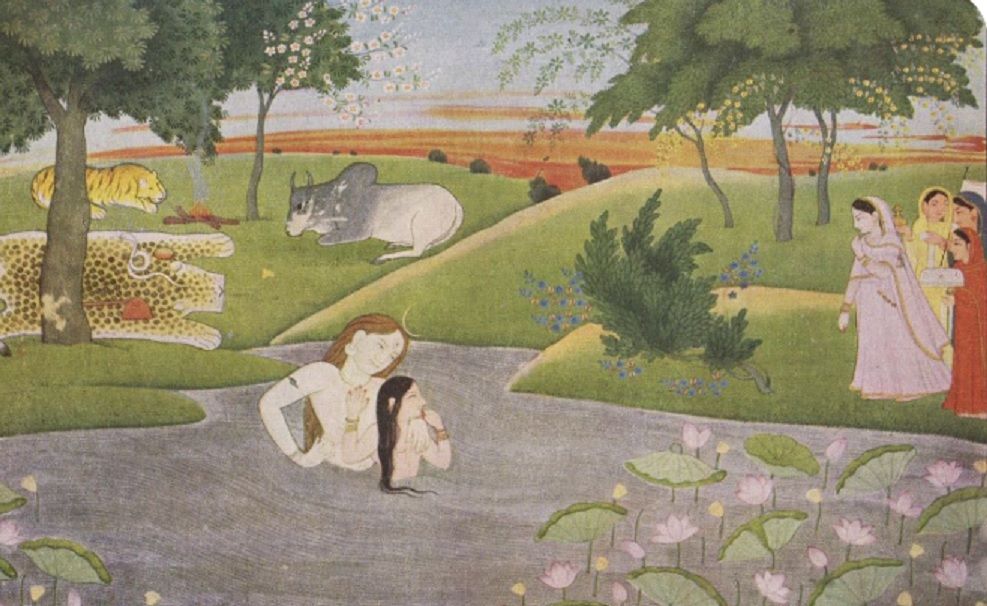

Marriott observed that to maintain this perceived purity, village Brahmins seek to maximize interactions, communications, and other social transactions with those they perceived to be their equals: other "snowy-mountain-spring-water" beings. Among these are the Gods and Goddesses they invoke in their devotions.

Traditional Brahmins—men and women alike—in their culturally internalized social strategy, can thus be seen as very selective “lifestreams”: desirous of allowing only pristine "waters" to intermingle within their own.

To intermingle with muddied streams would divide their divisible lifestreams into flows of lesser purity.

Of course the streams of life within which present-day Brahmins frolic, in all their sincere attempts to live down their socially stratifying Laws, may puddle with muddy, fetid waters. But the social strategy of many Brahmins may still remain the same: They may tell you that the caste system died long ago, but they will most likely marry a Brahmin. Doing so will ensure that they maximize interactions and communications and communion with those they consider to be their equals while minimizing intermixing their lifestreams with others.

Of course, some neo-Brahmins may actually feel proud of muddying themselves by mucking around in non-Brahmanical waters.

That makes many present-day Brahmins pretty much like all the rest of us.

The Brahmanical concern with what they see as purity necessitates a caste of Untouchables eternally tasked with treating sewage.

How can they ever ascend the rungs of the karmic social ladder? The theory is that after millions of births, an untouchable may be reborn as a Brahmin.

Is it any wonder that some Untouchables seek a shortcut: to transcend, parody, and deconstruct the whole system, with all of its thought constructs?

To clear thinkers, such a strategy is viable, not unlike that of an enterprising young Spanish girl hundreds of years ago in Spain. In the middle of a dark night, inflamed with spiritual longing, the young Teresa de Avila took the hand of her brother within her own and, unseen, slipped away from the strict confines of her walled city.

She was headed for Southern Spain, where she knew she was certain to be martyred by Moors, with whom her countrymen were battling.

Her logic was impeccable: If Divine Life exists not here on earth, then why waste a moment mucking around in the mire? Why not just martyr oneself to Moorish swords and arrows and lances, and get to Heaven forthwith?

Untouchables may be driven to similar extremes.

Crazy?

Consider their alternatives.

Having written all of that, I suggest maintaining a modicum of skepticism toward what I have just written.

This is because, although I have close Indian friends who inform me of such matters, I have based this note on the thinking of a Western anthropologist, McKim Marriott.

James Clifford asked whether anthropologists (such as Marriott) are like the young woman anthropologist in the image above. She is surrounded by exotic artifacts from far-off lands but with no evidence of ethnographic experience informing her writings, which instead seem inspired by the God of Time and a host of Divine companions. She gazes upward, toward Adam, Eve, and the serpent. Above them stands a redeemed couple from the Apocalypse. On each side glows a luminous triangle bearing the name Yahweh, written in Hebrew script.

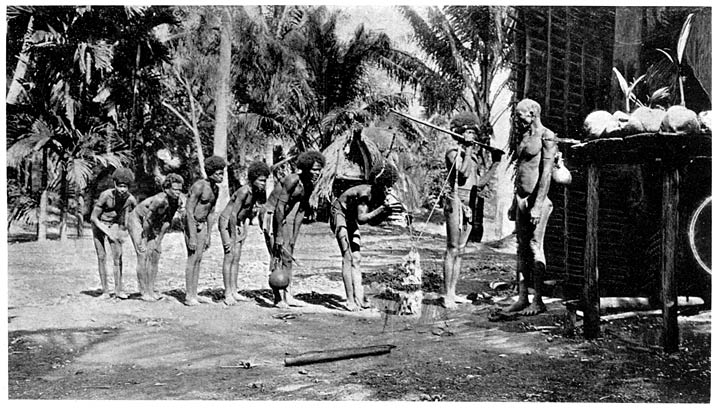

Or is an anthropologist someone who is more engaged with the culture being studied, as in this frontspiece photo of Maliknwski’s Argonauts of the Western Pacific. Its caption? “A Ceremonial Act of the Kula.”

A Trobriand chief stands at his door. Six youths stand, bowing. One of them sounds a conch while another presents the chief with a necklace in a traditional Trobriand rite of exchange.

The last young man in the procession, however, displays a gesture of ethnographic engagement. He stares away: into the Western gaze of the camera.

It is good to ask the question Clifford asks because in this postcolonial era, the peoples who suffered through colonialism only to now become objects of cross-cultural studies, often say they do not recognize themselves in such studies.

They are not especially happy about that fact.

Therefore, increasingly, the activity of cross-cultural representation itself has found itself in question.

After all, all such representations are fashioned of thought constructs.

The tradition the scripture arose from was a mature, self-deconstructing tradition. It was aware that its doctrines also are thought constructs.