Kashmir Shaivism: An Exposition

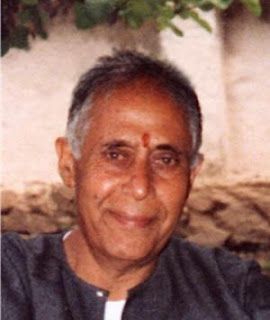

By Swami Lakshmanjoo

Translated from the Kashmiri and Edited by Pandit Dina Nath Muju

kenesitam patati presitam manah kena pranah prathamah praiti yuktah kenesitam vakam imam vadanti caksuh srotram ka u devo yunakti

Kena Upanishad

Energized by whom does the mind cognize the world? Prompted by whom does the first life-breath vibrate? Who enables the voice to speak? Who directs the eyes and ears?

yan nu ma iyaṃ bhagoḥ sarvā pṛthivī vittena pūrṇā syāt kathaṃ tenāmṛtā syām yenāhaṃ nāmṛtā syāṃ kim ahaṃ tena kuryām

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

If the entire earth, with all its wealth and pleasures, were mine, how can that make me immortal?

What use is that which cannot help me to go beyond sorrow, bondage, and ignorance forever?

In ancient India, such and similar questions asked by the Rishis at the dawn of civilization and investigated by them gave rise to various philosophies and systems of thought. Questions continued to arise and to be answered, differently in different epochs. Whereas answers provided by most of the systems, such as Vedanta and Yoga, acknowledge the authority of the Vedas, some, like Buddhism, challenge this authority and attempt to answer independently.

Shaivism, although not denying the supremacy of the Vedas, proceeded to answer, claiming the Tantras as its source.

The Tantras are treatises of remote origin, independent of the Vedas, and of anonymous authorship. They are accepted by their adherents as of divine origin, like the Vedas, and are generally in the form of dialogues between Shiva and Shakti (The Unmanifest and the Manifest). They are ninety-two in number and are divided into three categories: dualistic, mono-dualistic, and monistic.

Kashmir Shaivism, as it is called, is a recent recession of Tantric Shaivism and is absolutely monistic. It owes its origin to sage Vasu Gupta, who flourished in the first half of the ninth century, AD and gave us the famous Shiva Sutras, which form its basis. He was followed by an eminent line of thinkers and writers such as Somananda (9th Century AD), the author of Shiva Dristi and founder of the Pratyabhijnya school of thought; Utpalacharya (circa 10th Century AD), author of Ishwar Pratyabhijnya; and Abhinava Gupta (11th Century AD), author of a number of works, chief among which stands Tantra Loka, in thirty-seven volumes (an encyclopedia of Tantric knowledge) — to name only three of the most distinguished philosophers among them.

This system postulates three ways of realizing the Shiva State — the Ultimate Reality.

• The first discipline is termed Anav-upaya, the method suitable for a limited being. It is meant for those who cannot yet rise above the interests of their limited selves and for whom the concrete and tangible is still more important than the abstract and intangible. So, in this method are included proper postures (asana), breathing exercises (pranayama), and repetition of sacred words (mantra). An aspirant on this path is usually required to concentrate on some symbol, such as triangle, Swastika, cross, or so on, or on some image, maybe of one's preceptor (guru), or of some deity, while repeating the sacred word given to one by one's preceptor. At a later stage, the preceptor may teach one to concentrate on the psychic centers in one’s body. If properly done, this can lead to the awakening of psychic faculties and even more, depending on one’s earnestness, purity of conduct, and the extent one can go beyond one’s limited self. This method is also called the method of action (Kriya-upaya).

• The next method, higher than the first, is called Shakta-upaya, or the method of Energy. Here, the external symbols and aids are dispensed with. No special posture or breathing exercise is considered necessary. Mantra is retained, but its verbal repetition is replaced by deep contemplation at a non-verbal level. The aspirant is required to contemplate so earnestly and with such awareness that the aspirant becomes one with the spirit of the Mantra and is permeated by its energy—for a Mantra is not merely a rhythmical arrangement of words, but a form of energy. Thus consciousness expands beyond the limited self. The greatest mantra is Hamsa (I am That). By contemplating the different facets of this mantra, the aspirant is led to negate the individual “I” and merge it into the universal “I.” This method is also called the method of wisdom (Jnyan-upaya) and is practiced long, even by the most advanced aspirants. It is considered quite capable of leading one to the next, which ushers in the highest Reality.

• The third and highest method is called the Shambhav-upaya, or the method of Shiva. At the first stage, bodily organs are involved in the various practices prescribed therein. At the second, bodily organs have no important role to play, as such, but the function of the mind at deep contemplative levels remains and has a very important role to play. Now, however, in the last state, even the mind has to be dispensed with. No rules can be laid down here, and no practices prescribed. Here the aspirant’s only concern is to be in that state of awareness where the movement of thought comes to a stop. The only qualification is earnestness combined with deep, penetrative insight. Hence, this method is also called the method of will (Ichhopaya). With the cessation of thought processes, the state beyond mind dawns. To let it happen, suppression or sublimation of thinking is not the way, but rather an intense awareness of each thought and feeling, at all times (including during sleep) is needed. In this intensity of choiceless attention, the ending [or fading away] of any thought, feeling, or perception can result in the dawning of Enlightenment. When the cup is empty, something new can fill it.

Any method, however subtle, can be only a result of a thought process—a product of mind. Hence it cannot touch that which is beyond thought, beyond mind. The mind can penetrate, at best, up to its own frontiers. Do what it will, it cannot go beyond its limits of time and space. Methods, one and all, are not only useless at this stage but rather obstacles. A method implies duality—a seeker and an object of search, a devotee and an object of devotion. The ever-present, all-pervading, all-knowing Totality needs not to be beseeched or coaxed. It arrives unsought, like a fresh breeze from the mountaintop, when the mind is free from thought and seeking.

When an aspirant comes to the clear realization of this fact, the Shambhav-upaya becomes An-upaya (No-Method) or what may be translated as Beyond-Method. In this state of non-dependence and effortless awareness, there is neither acceptance nor rejection, neither justification for nor identification with any feeling or thought. In this void, the worshipper is the worshipped. This state is not beyond action and wisdom only, but beyond will, too. It simply is.

II

Such is the path, yet there are hints available here and there, given out of compassion by those who have scaled the great heights, to help and encourage an earnest disciple to set his or her foot on the path. Shaiva Tantras are replete with such hints, though their esoteric meaning often remains obscure to those uninitiated in their mysteries. One of these, the Vijnyan Bhairava Tantra, is more explicit and expounds 112 unique ways of transcending the limitations of individuality. These ways are really meant for advanced seekers, who have reached that state of self-discipline where the need for laying down any formal discipline ceases. For such earnest aspirants, some situations likely to be met with in the ordinary course of life, and some practices—for performing which one need not withdraw from ordinary activities of life necessary for physical and social well-being—are delineated. Shaivism does not advocate external renunciation and running away from the world—for the cosmos is in Shiva and Shiva is in the cosmos. There is no situation where Shiva is not.

We cognize the external world by five senses—hearing, touch, sight, taste, and smell—which help us to gather knowledge, but which also, often, lead our minds astray. It is for this reason that usually all spiritual disciplines prescribe ways and means to curb and withdraw the senses from the world of manifestation. Shaivism here takes a radically different stand. It attempts to make these very senses and their pleasures stepping stones for the upward path: tasting, smelling, seeing, touching, and hearing. It elevates the pleasures of the senses from the plane of sensuality to that of increasingly refined sensitivity.

This approach appears, no doubt, alluring, but the neophyte must be forewarned. It is perilous too. An undisciplined, unwary, or over-zealous beginner may easily stumble on the very first step and break his limbs. A very cautious approach is needed. A seriousness of purpose to realize the Truth and a whole-hearted devotion to it alone, form the prelude to this search. Plainly speaking, it is not meant for those who are still held by the desire for gross pleasures.

With this little introduction, we shall now describe the ways as given in the above-named Tantra. The ways, however, cannot be grouped under one head. There are some that belong to Anav-upaya, many which are of Shakta-upaya, and a few of Shambhav-upaya. Yet, if one would pursue any one of these steadfastly and intelligently, it can lead one, by stages, from Anav to Shakta and from Shakta to the Shamabhav state. It is not desirable that an aspirant should try all the ways. Different ways are annunciated to suit different temperaments and different people at different stages of the path. So, an earnest aspirant should select one or two ways only, which, after very careful consideration, appear to the aspirant to be most suitable, and then try these with perseverance and faith. After one has made some progress, if one finds it necessary, one may change to some other way or ways, but one should, in no case, try to be too ambitious and select a large number of ways at one time, nor so fickle as to make constant changes. We shall attempt to explain, as clearly as possible, even things that have remained secret so far, but even then we cannot claim to replace the direct guidance of a worthy preceptor.

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

Note:

I received two letters from Pandit Dina Nath Ji. The first, in response to my letter of September 3, 1974, was dated October 13, 1974. It was accompanied by Panditji's "Life and Teachings of Swami Lakshmanjoo."

The second was dated April 20, 1975, and was accompanied by the above "Exposition of Kashmir Shaivism" and by his collaboration with Swamiji carrying across the meaning of the Vijñāna Bhairava into English.

Thus, for about five months, Panditji and Swamiji worked on this collaborative version of the scripture before sending it off to Santa Barbara. As a Religious Studies scholar at UCSB, I naturally developed an interest in the scripture.

I had received diksha from my teacher some years before and was content within myself and so felt no need to add on other techniques. In addition, my teacher and Swami Lakshmanjoo befriended one another and compared notes. This resulted in Swamiji proclaiming that my teacher was teaching Kashmir Shaivism, nothing else. This perhaps is because my teacher's emphasis had always been on the unity of Knower, Knowing, and Known. Lakshmanjoo's advised us to stick with the meditation we all had been doing for some years.

Upon studying the scripture, however, I discovered that there were some verses devoted to situations that naturally arrive in the course of one's life, that clear away duality.

One was when lying on my back and gazing up at a cloudless expanse of blue.

Another, when surrounded on all sides by pitch-black darkness.

Neither of these situations support day-to-day thought streams.

Through years of intensive meditation, I found that anytime the mind approached anywhere near the shorelessness of pure awareness, it tended to dissapear.

So there is wisdom in carefully selecting one way, and sticking with it.

▼▼⛛▼⛛▼▼

To enable his commentary on this scripture to endure down through the ages, Swami Lakshmanjoo left it in two other forms:

(i) a series of videos gracing each verse, which over a few years, John Hughes of the Lakshmanjoo Academy recorded, and

(ii) Swami Lakshmanjoo's textual embodiment of the tapes, The Manual for Self-Realization: 112 Meditations of the Vijñāna Bhairava Tantra (edited by John Hughes).

Both are treasures! In each, Swamiji comments on the scripture while responding to questions from his students. Swamiji emphasizes that the video version transmits his teaching with a higher level of fidelity.

Published by: